James Gray has long been heralded as an underappreciated director by his steadfast supporters in film criticism. From Little Odessa (1993) to The Immigrant (2013), Gray’s films have always had a strong resonance with critics and yet have seldom had that rapturous reception translate to commercial success. Save for the Joaquin Phoenix-starring We Own the Night (2007) and Two Lovers (2008) nearly all of Gray’s films have had poor box office returns. And while other directors may begin feeling self-conscious about their work, Gray thankfully appears to be doubling down and barreling ahead with his wonderfully introspective The Lost City of Z.

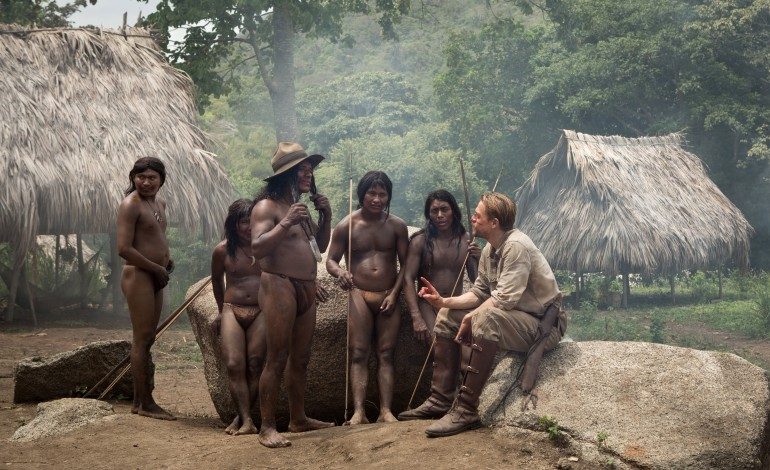

Based on the true story of British soldier-turned-Amazonian explorer Percy Fawcett (Charlie Hunnam), The Lost City of Z is an adaptation of David Grann’s 2009 book of the same name. Much like Apocalypse Now’s Colonel Kurtz, Gray’s newest film tells the nobler story of Fawcett as he slowly becomes increasingly obsessed with his exploratory conquests in the Amazon. Joined by fellow explorer Henry Costin (Robert Pattison) and a few other Brits, the surveyors launch several trips into the dangerous rainforest, heading deeper into the uncharted land with each expedition—all in the hopes of finding a great lost city that could potentially be the real El Dorado.

Undeterred by their colleagues’ racist dismissals, Fawcett wholeheartedly believes there to be an advanced civilization deep within the jungles. Supported by his steadfastly patient wife, Nina (Sienna Miller), Fawcett and his team return time and time again, coming closer to discovering their lost city with each subsequent journey. But with old-age and waning domestic interest quickly encroaching, Fawcett launches one last expedition, this time aided by his grown son, Jack (Tom Holland) to uncover what he has desperately been trying to prove for decades.

The Lost City of Z is a rapturous film that captures the dangers, mystique, and spectacle that is the unexplored Amazon Rainforest. With a penchant for shooting on 35mm print, the green, brown, yellow, grey and orange tones of the rainforest coalesce to make a mesmerizingly gorgeous portrayal of the swampy South American locale. From the murky piranha-infested waters to the sickly malaise of Fawcett and his fellow explorers, Gray’s newest film is a visually stunning work that harkens back to New Hollywood cinema.

Gray’s more recent preoccupation with accuracy in his period-pieces has paid off as not only does the stylization perfectly capture the mood and atmosphere of early 20th century Britain and her colonies, it also successfully showcases the sociocultural nuances of Britishness. Much in the same enthusiasm that so many young British men marched off to war in the hopes of finding adventure and tales of bravery, Fawcett ventures off into the Bolivian rainforest to prove his militaristic worth all while showcasing the quintessential British mettle.

Gray takes the time to unfold a generic narrative into a dark examination of a psyche’s proclivity for utter fixation. From the absurdist unveiling of an opera house deep in the jungle to a death stricken boat ride down the river, it seems there are plenty of homages to Francis Ford Coppola’s seminal Apocalypse Now. But while Coppola demonstrates the ill-conceived morality of the obsessed Kurtz, Gray deliberately maintains the moral ambiguity of Fawcett. While he may be dismissive of his family, threaten his relationship with the royal society that funds his trips and push his teammates to the brink of insanity, Fawcett’s drive is one that is muddled in ethical uncertainty. He is shown to be both caring and reckless; driven and yet hopeless; mad and yet calm. It is the portrait of a man dead set on his goals—regardless of the cost.

At one point, he is asked why he left his family for the insanity, danger and grime of the Bolivian jungle to which Fawcett has no response. He is drawn to it much like men are drawn back to war after their tours. It is an indication of insanity, and yet Fawcett maintains his sense of mental stability as the group treks further into the unknown. Hunnam’s adeptly charming portrayal of Fawcett signals to the viewer his motivations and yet demonstrates the juxtaposing qualities of them. Clearly Fawcett has a disturbing self-destructive need to find glory, and yet he and his colleagues sell themselves on the idea that they are quelling racist rhetoric and opening people’s minds up to the possibility that the natives of the Amazon are capable of civility as well.

Fawcett continuously makes it clear that to him, the greatest failure is unfulfilled glory. After his involvement in the deadly Battle of Somme, Fawcett is shattered to learn that he might never see again. And while most men would sob at the idea of never seeing their loved ones again, Fawcett weeps at the notion that he may never return to his mistress—the ever-elusive jungle. It is a devastation that Fawcett can barely overcome and one that hangs over his head—leading to the ill-conceived 1925 outing with his son that would be the young Jack’s first, and unfortunately, last one.

Verdict: 5 out of 5

James Gray’s The Lost City of Z is a film that not only astutely recreates the absurdist inscrutability of the dangerous jungle, it also works tirelessly to demonstrate man’s monomaniacal tendencies. But while other directors may have made the hackneyed decision to showcase an overt descend into madness, Gray does a skillful job of relishing in the moral ambiguity of his film’s protagonist. Coupled with the enthrallingly beautiful camera work of Darius Khondji and perceptive performances of Sienna Miller, Charile Hunnam and a surprisingly fine showing from Robert Pattinson, The Lost City of Z is a is yet another polished addition to the director’s acclaimed repertoire.