When you hear the term ‘noir’ in relation to film, what comes to mind? If you have any knowledge of French, it might evoke thoughts of something dark, perhaps a lawless society, pipe-smoking detectives, or even the character Spider Noir from Into the Spider-Verse. The noir genre and its more recent neo-noir offspring have been captivating audiences for decades, continuously evolving while maintaining a dedicated following. From classic noir films like Vertigo and The Maltese Falcon to more recent additions like Oldboy and The Dark Knight, this genre has left an indelible mark on American literature and the world of cinema since the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Noir’s unique appeal lies in its use of shadow play, ambiguous framing, morally complex protagonists, and plotlines that emphasize the weight of the world on the shoulders of a few. To demonstrate this, let’s take a closer look at where it all began – the early 20th century.

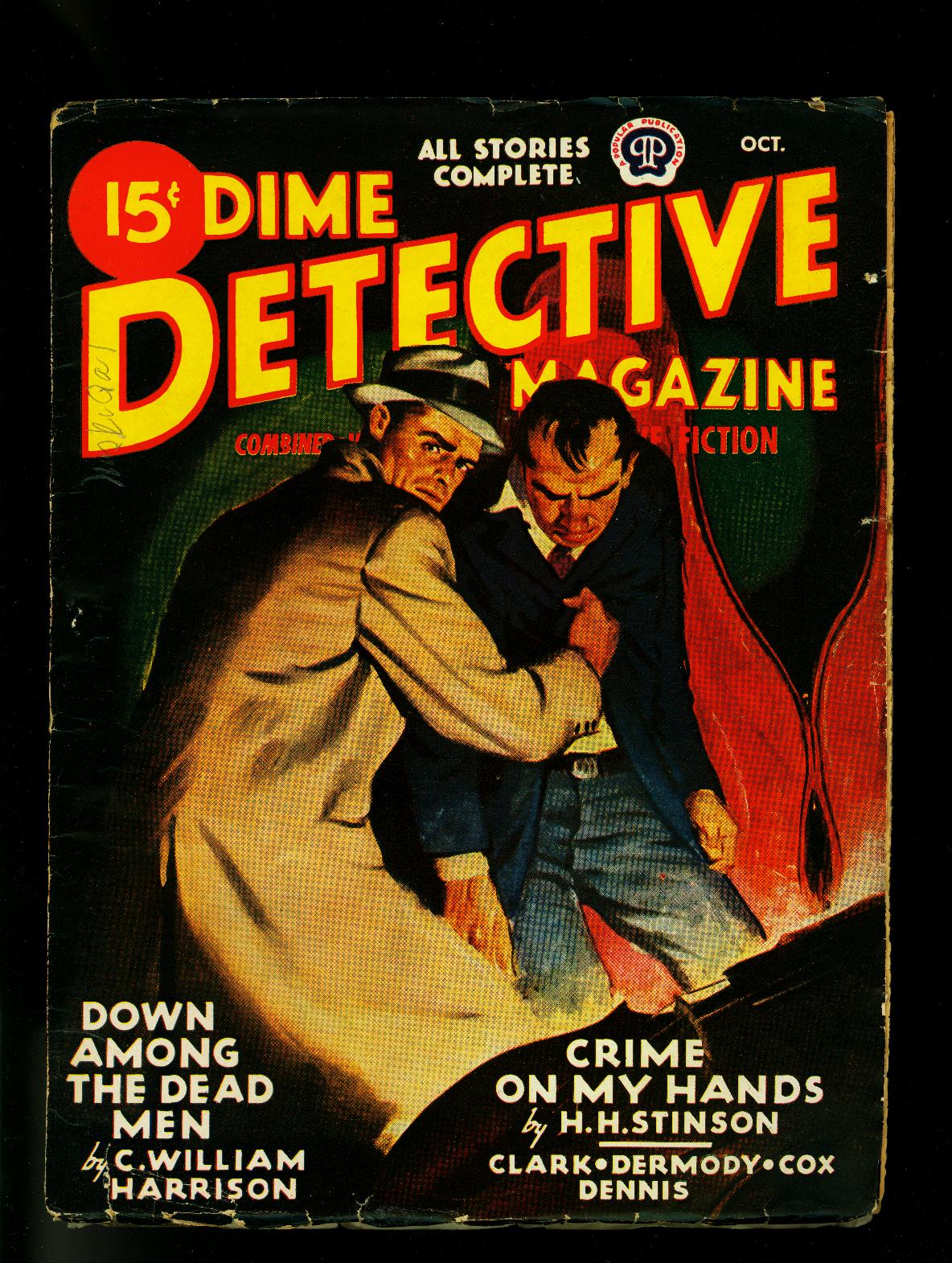

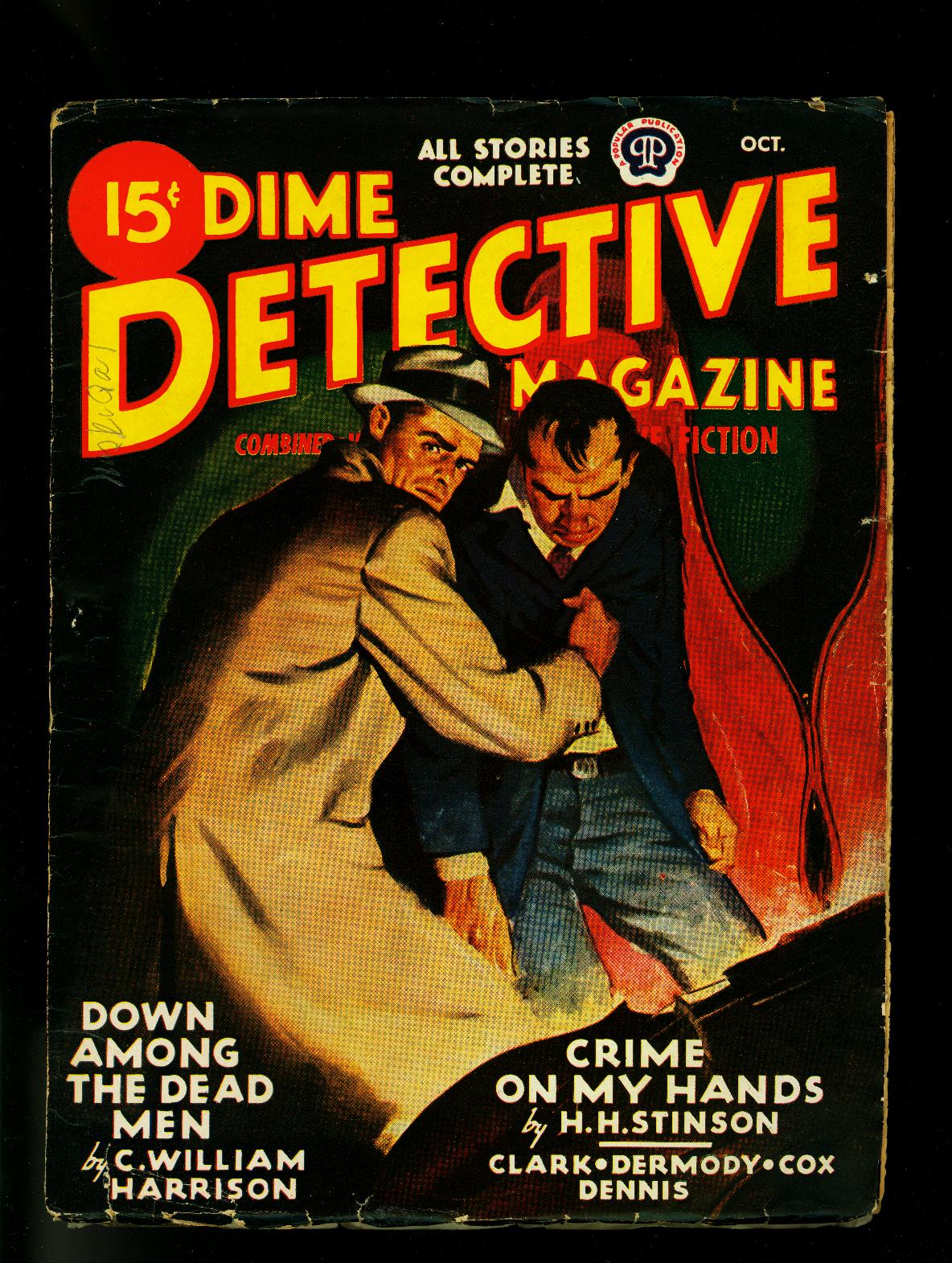

Economically, the Great Depression wreaked havoc, and culturally, the literary world was gradually letting go of the traditional Sherlock Holmes detective narratives. Instead, a new genre began to emerge within the pages of pulp magazines – inexpensive entertainment magazines that catapulted authors like Ellery Queen and Agatha Christie to fame. Mysteries were becoming darker and more complex, and the lines between good and evil grew increasingly blurred. This marked the rise of the hardboiled detective novel, reflecting the cynicism and despair of the era. Detectives of this era became more active in their pursuit of justice in a corrupted world where trust was a rare commodity. This genre laid the foundation for what would later become the noir genre in cinema.

Noir cinema and hardboiled literature often go hand in hand, sharing a defining backdrop of lawlessness and unforgiving circumstances. Hardboiled protagonists are far from the academic and methodical Sherlock Holmes of the past; they are rough around the edges, and their moral compass often points in a more ambiguous direction. However, hardboiled is not limited to detective novels; it also features seductive femme fatales and ruthless gang leaders entangled in heinous crimes. It’s no coincidence that hardboiled novels gained popularity during the Depression, while noir cinema emerged after World War II.

The turbulent mid-20th century, marked by global instability, wars, and social upheaval, created the perfect environment for this style. Prohibition fueled fantasies of bootlegging, and economic insecurity during the Depression made the anti-hero gun-slinging protagonist relatable. These characters traversed crime scenes, ventured into the shadowy underworld, and engaged in epic fight scenes, resonating with a generation facing unprecedented challenges.

The term “noir” was not coined until the 1940s and 1950s, but the thematic elements of hardboiled novels had been seeping into cinema since the 1920s. Translating to ‘black cinema’ in French, noir films visually emphasized darkness. Much of noir cinema is characterized by shadowy settings, often taking place at night or in dimly lit environments. Stylistically, many noir films incorporate Dutch angles and other unbalanced framing techniques to enhance the narrative’s sense of ambiguity.

As previously mentioned, noir heroes often resemble their hardboiled counterparts, embodying the ‘anti-hero’ archetype and navigating cynical storylines. Addressing gender in noir film is a complex topic, but for simplicity’s sake, masculinity is toxic and women are fallen and fatal. While not a defining feature, many noir films explore sexuality, particularly its use as a weapon, often embodied by the infamous femme fatale. Protagonists in noir films are typically morally ambiguous, leaving the audience uncertain about whom to trust. What’s even more enthralling is that noir stories often lack a tidy conclusion. The protagonist’s journey might come to a resolution as they exact revenge or save a loved one, but the corrupt empire that orchestrated the ordeal typically remains intact, deviating from the typical outcomes seen in action or crime films.

While many might associate noir with the classic Hollywood era of the mid-20th century, the reality is that noir remains a vibrant and influential force in the world of cinema. In addition to the examples mentioned earlier, such as Vertigo and The Maltese Falcon, noir continues to thrive with the emergence of films like the John Wick series, Martin Scorsese‘s 2010 Shutter Island, and Nicolas Winding Refn‘s Drive, all of which have made significant contributions to the noir genre within the past 15 years. However, some scholars have recognized a shift from the classic noir style, giving rise to a new ‘neo-noir‘ subgenre that revitalizes the classic noir aesthetic and applies it to contemporary films. Even with this new classification, neo-noir maintains the stylistic essence that has defined noir cinema for decades.

The rise and evolution of noir can be traced throughout American history, mirroring societal changes and evolving tastes. Drawing inspiration from the hardboiled detective novels that gained prominence in the early 20th century, the visual elements that came to define noir cinema breathed new life into these hardboiled narratives. The genre stands out as one of the most thrilling styles of storytelling, characterized by morally ambiguous characters navigating a lawless society, which keeps the audience in a perpetual state of uncertainty regarding whom to trust.

However, noir did not fade away during its classic Hollywood heyday. It has continued to gain popularity in recent thrillers, such as the John Wick chronicles and The Dark Knight. While these films may be considered neo-noir due to their creation during the noir revival, they retain the fundamental elements of darkness and moral ambiguity that have always captivated audiences. By examining the box office success and the widespread buzz generated by these recent additions to the noir family, it is evident that the genre shows no signs of diminishing any time soon.