Today’s so-called ‘smart’ technologies of remote platforms and virtual communications promise increased efficiency in every corner of life, supposedly allowing for more leisure time with our family and friends. The coronavirus has, ironically, heightened society’s dependence upon mobile software to a new extreme, posing the necessary question: Why does it seem like we’re always running out of time, with little left to form meaningful relationships?

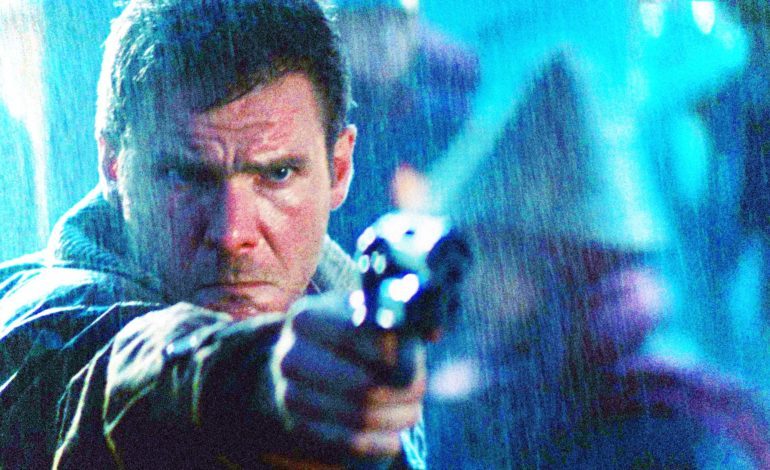

Set in Los Angeles during the not-so-distant past of November 2019, Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner paints a fitting portrait of the seemingly incompatible relationship between man and machine. The thought-provoking sci-fi film follows Deckard (Harrison Ford), an ex-bounty hunter whose task of “retiring” a group of Tyrell Corporation’s superhuman Replicants clashes with his love interest in one Replicant girl. Scott’s skeptical outlook toward technology and its underlying ideologies is streamlined throughout the film via breathtaking special effects and an unusually effective production design. The movie’s indictment of and disillusionment with technological progress is revealed in Scott’s bleak portrayal of a society where the marginalized victims share the same space as the exorbitantly powerful.

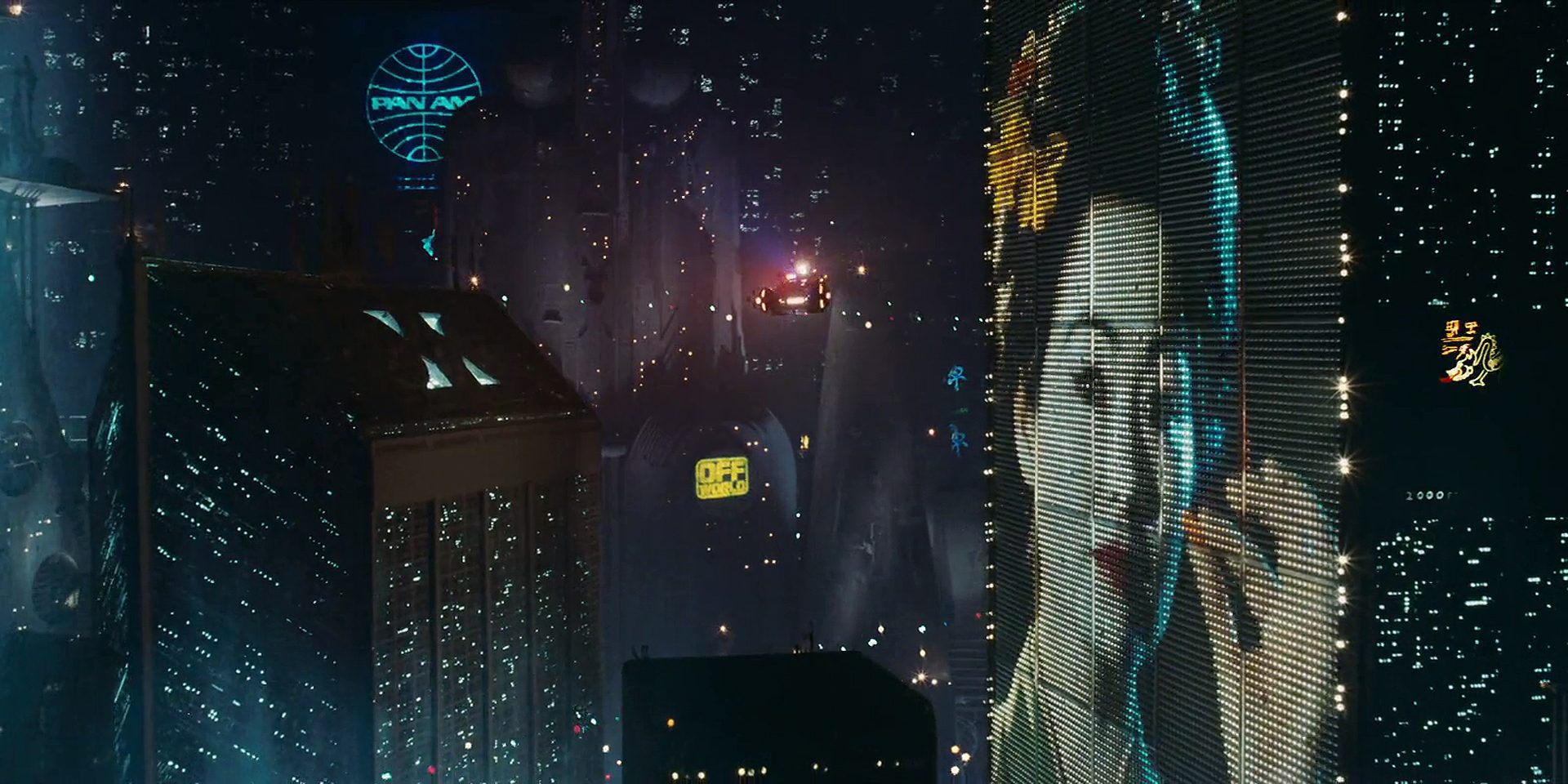

Jordan Cronenweth, the film’s cinematographer, unrelentingly takes audiences into these confounding areas using a host of camera movements. Infusing classical film noir’s chiaroscuro lighting and venetian blinds with futuristic imagery, his atmospheric establishing shots of high-rises with colorful advertisements differ strikingly from the decayed streets reminiscent of a bygone era. From the iconic image of an eye reflecting the flames of LA’s industrial landscape to the artificially glowing eyes of Tyrell’s owl, the notion of a visionary society able to perceive the future with owl-like wisdom is completely shattered. With the help of densely layered visuals, Blade Runner offers a glimpse at a world of perpetual rain and smog, mirroring the causal link between the exploitation of Earth’s resources for transcending human capabilities and its dire environmental consequences.

In keeping with Blade Runner’s presentation of societal devolution amidst corporate attempts at future development, Vangelis’ blend of classical and electronic tunes resembles this ambiguous presentation of truth and fiction. Even worse than an imperfect world is one where the line between inferior and superior is blurred, and the dissonance between classical chimes and modern synthesizers keeps listeners on their toes, bereft of any familiar rhythms to latch onto. The ominous Japanese ensemble piece “Ogi no Mato” is especially noteworthy, as the ancient melody, stripped down to its narrative form, accompanies a large advertisement of a Japanese woman, signifying the dilution of high art. This process mirrors the dehumanization underlying scientific advancement, where the intoxicating hope for potential gains betrays the overshadowing cost of pain and loss of humanity that comes with a disposable labor force.

Blade Runner experiences no shortage of acting talent, as the characters played by Harrison Ford, Sean Young, and Rutger Hauer take this concept of dehumanization quite literally in ambiguously embodying human and Replicant traits. One of the age-old debates surrounding the film deals with Deckard’s cryptic identity, but the fact that his role as a blade runner demands the inhuman killing of increasingly humanlike androids does not support any arguments in favor of his humanity. Rachael’s character takes this conundrum to a wholly different level, given that her self-awareness as a Replicant with artificially-implanted memories brings her very being into question. The same goes for Roy, yet another Replicant whose iconic monologue of transience breathes life into an existentialism that applies to humans and Replicants alike, suggesting the thin line between the two.

Blade Runner’s brilliant screenplay by Hampton Fancher and David Peoples uses Philip K. Dick’s 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and all its rich undertones as another vehicle to puncture the fragile truth of institutional narratives. The very idea of a dystopian society presents a pessimistic outlook on what’s to come, and the novel embodies this message by reflecting on human nature following the horrific acts committed using machinery and weaponry of the Vietnam War. If we were to place this script within the realm of film noir, Blade Runner certainly adopts relevant thematic and stylistic elements. Yet the film stands apart by deconstructing technology’s promise for a hopeful future, all while fracturing the truths we take for granted.

With Denis Villeneuve’s release of Blade Runner 2049 a few years ago and his upcoming Dune project wrapping up, the film industry still finds ways to explore today’s affairs using futuristic material. The fact remains that technology relies on humans, but when humans in turn rely on technology in such a way that we socialize solely through online platforms, life as we know it will never return to the normalcy that was taken for granted pre-coronavirus.