So here’s a question: how do we talk about screenwriting in film? Let’s say we go down to the multiplex and catch a double feature, and at the end of both screenings we just have a feeling in our gut. “That screenplay was amazing,” a little voice says after the first film. “That screenplay was terrible,” it whispers after the next one. We just know both of these things, we’re sure, but what’s the difference? How do we explain what sets off our quality sensors around a film’s script? Do we try to wade into the increasingly murky waters of dialogue evaluation? Try to break down what the film’s thematic goals were? We can always fall back on examining the film’s implementation of character arcs, although that has its own set of problematic baggage.

Usually, though, these conversations circle back to one very particular word: structure. And no, I’m not talking about film’s adherence to the prescriptive model of three acts, or following the Campbell’s “Hero’s Journey,” or any of that other formulaic junk, although that can certainly play a part in it. I’m talking about things on a more elemental level: what’s the architecture that has gone into crafting the way that the audience experiences the story? Once a writer has decided that he’s going to tell a story about an X who meets a Y and then has to overcome a Z, how do they present the information to the audience and guide them to a very specific story experience? How do you get information into the audience’s head without it feeling like you’re feeding them bits and pieces for later use? How do you get an understanding of the world and the characters into your film without stopping the film dead in its tracks? In short, how do you quickly move the pieces around the narrative chessboard without the viewer’s spotting your endgame ahead of time?

Here’s an example: consider Billy Wilder’s The Apartment. Early in the film, the protagonist has to wait outside his home while one of his office superiors who rent his apartment for dalliances with a mistress finishes up. After they leave – far after the agreed upon end time – Buddy has to clean up, make himself a sad little dinner, and put up with his neighbors berating him for loud noises he wasn’t the cause of, all before taking a sleeping pill and crawling into bed. It’s only then that his phone rings: another one of his office bosses has need of the impromptu love nest, and wants Buddy to clear out for half an hour. “But I’m already in bed!” our protagonist protest weakly. “I’ve taken a sleeping pill!” No luck – his superior presses on, Buddy relents, and soon our man is once again waiting outside while a two-person party rages on inside his apartment.

This is outstanding screenwriting structure, largely because of how much information it plants in the audience’s head. We get to see the arrangement that Buddy has with his bosses, and we get a sense that he is being unfairly exploited and getting more than he bargained for. We get a sense of his routine, and some insight into his loneliness. We even get a little bit of who he is as a person: he’s not totally spineless (he does try to stand up for himself) but he’s not great at confrontations. This is a script that is serving multiple masters all at once, drawing the audience’s attention to half a dozen different fronts in a matter of minutes. Perhaps it’s greatest triumph, however, is what it smuggles in. It’s so small: “I’m already in bed! I’ve taken a sleeping pill!” It sounds just like a reasonable argument for why Buddy doesn’t want to leave the house – in fact it is just that – but it also sets the stage for everything that happens during the fateful Christmas Night sequence later in the film. Amidst the rush of activity, the film has silently loaded a gun that won’t go off for an hour and no one’s the wiser. That’s good structure.

You know who else has impeccable storytelling structure? These guys.

Let me explain. And consider yourself spoiler warned for all things Avengers: Age of Ultron.

Now, in the few weeks since Ultron hit theaters there has been a lot of conversation about the merits of the film, especially relative to its big brother from 2012. Some conversations, including our own review of the film, have largely been appreciative of the film’s strengths. Others, such as our revisionist history piece, have been quicker to point out the elements of the film that have felt more out of place or unsatisfying. There have been those who believe that with this film Marvel has finally bitten off more than it can chew with its multi-film-continuity-franchise extravaganza. And, of course, there’s been everything from think pieces to SNL parody trailers dissecting the way the film develops the character of Black Widow. There has been much love, but there has also been a loud backlash to the film. So loud, in fact, that when writer-director Joss Whedon retired from Twitter to pursue some new creative projects, the world’s knee-jerk assumption was that he had been driven to exile in order to escape the pitchfork wielding masses.

So I get it: Age of Ultron is not regarded as a perfect film. I’m not saying that. What I am saying, however, is that once you get past the content itself, when you move past the choices of what the story should be and which character should have a romance with whom to look instead at how it’s built, Age of Ultron is a structural juggernaut. The film has to do some extremely heavy lifting – it has lots and lots and lots of material to cover – but it has been assembled with the organizational precision of a Swiss watch.

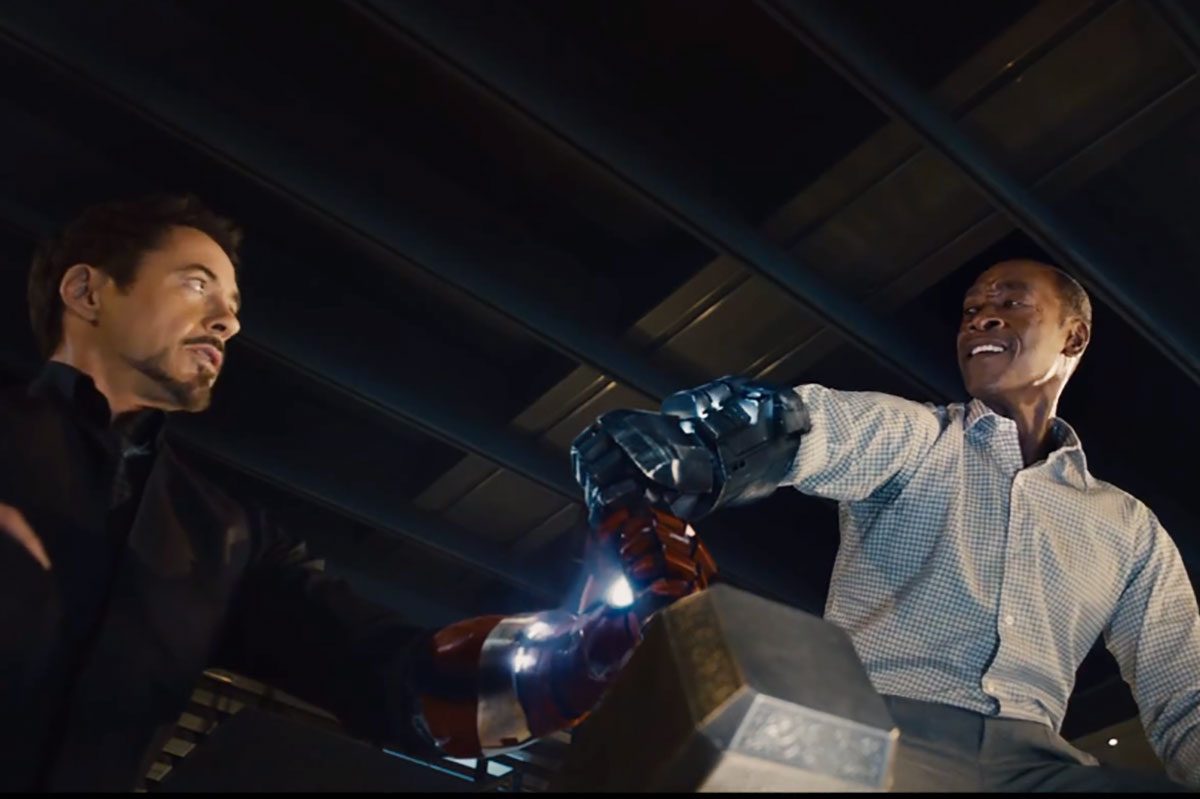

Want some proof? Look no further than this scene:

So what’s going on here? Why is this such an effective bit of screenwriting? First of all: it’s funny. Humor is always a good thing to have, especially in a movie that can go as dark and ponderous as parts of Age of Ultron. But more than that, it’s a blitzkrieg of character moments and reintroductions. Remember, Avengers has a unique challenge: it has to work as both the culmination of a large group of films and as an independent entity. It has to establish characters for newcomers and remind returning customers of its protagonists’ dominant characteristics, all without the luxury of introducing the characters within the universe of the film.

The solution that writer-director Joss Whedon finds is fairly ingenious: have each character tackle the same task in quick succession, and let their particular reactions to the undertaking do the talking for him. And indeed, each character’s one-on-one time with Mjolnir is like a microcosm of their most dominant traits. Tony Stark is cavalier and skeptical at first, then overinvested and prideful when he isn’t able to lift it. (And note the way that the film drops in a flash of Rhodes wearing a part of his War Machine outfit, a piece that will be important for the audience to remember at the film’s climax.) Bruce Banner (not seen above, but present in the final film) tries to turn his failure into a joke about his inability to control the Hulk – fitting for a man that’s constantly trying to reconcile the two warring sides of his existence. Black Widow doesn’t even try to lift the hammer; she’s above the men’s little games, but she’s also isolated from their camaraderie in a way. Captain America is all forward momentum: he goes for the hammer with no fuss, and simply shrugs and moves on when he can’t lift it. We even get a bit of insight into Thor’s mind when his bluster temporarily falters for the split second that Captain America is able to make the hammer budge.

So it’s funny, and it’s an artful way to bring character traits to the forefront, but Whedon isn’t done: the scene is also important because it reestablishes one of the mechanical rules of the Marvel Universe. Back in the first Thor film, Odin enchanted Mjolnir so that only those who are worthy can lift the hammer. By making the scene that revolves around this factoid a game and a rich character experience, the writer can remind us of this key detail without us ever feeling like we’re being lectured.

Why is this important? Maybe because about half an hour later it becomes integral to the confrontation between the Avengers and the Maximoff Twins in the arms dealer’s shipyard. At first Wanda and Pietro seem nigh unstoppable: she’s able to mess with the hero’s minds and he’s too fast to be touched by anything in their arsenal. And then it happens: Pietro sees the Mjolnir sailing past him, gleefully turns to grab the weapon… and is immediately sent sailing through a wall. This is how you build the beats of an action scene: you go from the characters’ personalities (in this case Quicksilver’s cocksure arrogance) and you pay off mechanics that are set up earlier in the film. Just like The Apartment, you make sure that multiple masters are served every step of the way.

Of course, the only thing better than effectively using a device two times is using it three times. Much, much later in the film, the Avengers are confronted with the character of The Vision. He’s the second android that Tony Stark and Bruce Banner have created, and the first one is currently in the middle of an extinction-level genocidal rampage, so the team is divided on whether they can trust this new character or not. And as an audience we are not unsympathetic: Captain America makes some pretty good arguments, and maybe some of us are also harboring reservations about handing over an incredibly destructive infinity stone to this untested A.I. character. Unfortunately, we’re nearing the two hour mark and don’t have time for an extended trial scene; we’ve got an explosive climax to get to. What we need is a way for The Vision to establish himself as a good guy beyond the shadow of a doubt in a matter of seconds, and for both audience and characters to trust him.

So he picks up Mjolnir.

Argument over, let’s go do that climax thing.

This is the true genius of what Whedon does throughout the film with Thor’s hammer – not just in the way that it’s seeded all across the film, but also in the way that it’s introduced. Imagine if in the first act of the film there was a serious scene where the Avengers discovered a mystical artifact that can tell good people apart from evil people. If it wasn’t immediately used, you’d recognize it as a plant and be waiting for the moment when it would come around to be paid off. It would be too easy to see through the film’s maneuvers and there wouldn’t be any chance for surprise. But since Whedon introduces the hammer through the use of levity, since its presence early in the film is justified as the foundation for jokes, we let something critical slip past us. The film smuggles in the key to its defining character moment half an hour into its runtime, and no one in the audience is the wiser.

Use it for comedy. Use it for action. Use it to advance the plot. And in every step of the way, use it for character. That’s good structure. This is what Avengers: Age of Ultron teaches us about strong, efficient screenwriting. And lest you think this is isolated to this single facet of the film, rest assured: all of Age of Ultron operates at this architectural level. Look at the way that Hawkeye and Quicksilver’s relationship evolves around the repeated iterations of a single line. Or the way that each member of the cast (except Hawkeye) has at least one scene where they are confronted with the possibility that they might be a monster, the film’s main recurring theme. Or even something as simple as the many inversions that pepper the film, such as the fact that in the first action sequence the Avengers use the Iron Legion suits to evacuate the Sekovian city but in the final scene they have to save that same city from the same robotic suits. On and on and on it goes.

Once again, I don’t want to get carried away with my praise of the film. Take another look at Brett’s Revisionist History piece for a sobering shot of what coulda, shoulda, and woulda been a part of a version of this film that was assembled with a different set of priorities in mind. (And no, I cannot defend the version of Thor’s weird cave sojourn that we saw in the film, as it is indefensible.) But once you get past the prime materials and begin looking at the craft, it’s hard to argue with the efficiency at which Whedon’s script covers acres of material, or the insidious skill with which it covers its tracks. And fortunately this isn’t the only film that works at this level. You see a similar structural command in the scene-shifting opening for Whedon’s Serenity, in the use of Agent Coulson’s cards in the first Avengers film, or… in basically anything that Billy Wilder ever did. These are the films that really illuminate the concerns of good story structure: how do you show your audience something, how do remind your audience of something, and how do you keep your audience from noticing something?