What makes you who you are? Is it your career? Is it your family? I think most people would agree that we are built out of a lifetime of experiences, ideas, knowledge, and dreams. Our pasts define our present and our future. Now imagine someone began dismantling you memories, one by one. Who would you become?

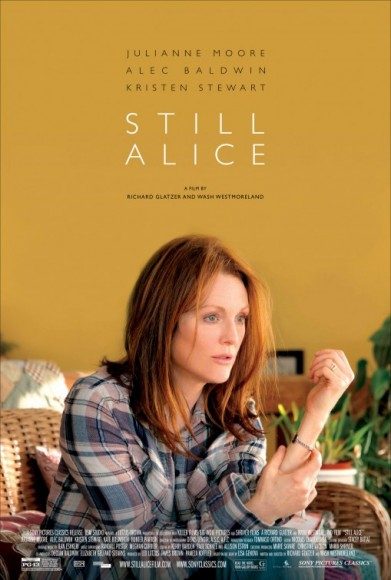

Alice Howland, played by Julianne Moore, has a picturesque life. At 50, she has a successful career as a linguistics professor, a loving husband and three smart children, and a brownstone in New York and a beach house. And then she starts to forget. Little things at first, words and appointments; then she starts getting lost, lost in places she’s known for years. She sees her neurologist and is diagnosed with familial early onset Alzheimer’s.

Films about disease, particularly mental disease, are tricky. It is difficult for the character not to get swallowed up in the disease, to simply become an embodiment of symptoms. Based on the novel by Lisa Genova, Still Alice evades these problems by focusing not on the disease, but on its implications. In many ways, Still Alice is not about Alzheimer’s, but identity. How do we remain who we are when a disease begins to steal more and more of who we were?

Julianne Moore delivers a captivating performance as the titular character. In a film that could have easily fallen prey to a made-for-cable mentality, she fills the role of Alice with grace, never becoming a caricature of the disease. Co-directors Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland give Moore the time and space to bring Alice to life, keeping her from deflating into a character that is defined solely by her disease. It’s a raw look at a struggle with disease, and one the feels wholly authentic. Alice lashes out at her family, deceives herself about her ability to continue working, attempts to use her illness to guilt her daughter into going to college, reacts to her disease in a profound flawed and human way. This is the great achievement of the film; Alice does not feel like a character, she feels like a person.

This is Julianne Moore’s film, through and through. Glatzer and Westmoreland keep the camera focused on her; there is rarely a moment that she is not on screen. The camerawork and editing take an appropriate backseat to performance. Cinematographer Denis Lenoir’s camerawork rarely calls attention to itself, only occasionally isolating Alice into a world of intensely shallow focus to make psychological points. The restraint is appreciated.

Alec Baldwin, Kristen Stewart, and Kate Bosworth also turn in well-timed and subdued performances as Alice’s husband and daughters respectfully. Baldwin brings a surprising amount of subtlety and depth to a man having difficulty watching his wife fade away, while Stewart continues to shine on the indie scene as Lydia, the family’s black sheep who finds difficulty attempting to reconnect with her mother before she fades away.

Mental illness is a difficult thing to capture. Alice at one point says, “I wish I had cancer.” Cancer is something that we can understand. It’s additive. You remain who you are, but with a tragic disease. Alzheimer’s subtracts from who you are. “We become ridiculous,” Alice says. One of the sad truths of the film is that we are more comfortable with diseases that attack the body than we are with ones that attack the mind.

The film’s power is underlined by the fact that co-director Richard Glatzer was diagnosed with ALS in 2011, shortly before production began on the film. Both diseases impair the ability to communicate and interact with the outside world, and it’s quite possibly it’s because of Glatzer’s understanding that the film is so successful. Alice is not a character defined by her disease. She is a fully realized human being experiencing profound loss.

Verdict: 4 out of 5

Still Alice focuses a steady and understanding eye on a disease that we don’t really like to look at. Julianne Moore’s captivating and devastating performance forms the heart of this struggle for identity. The film shows the horrible effects of Alzheimer’s, but it never becomes about the disease, instead providing a subtle and poignant look at how we define ourselves and how our impact on those we love comes to define them as well.