As often happens, I found myself comparing Get on Up to other movies as I watched it. The obvious comparisons are there, like Ray and Walk the Line and even the Jimi Hendrix biopic Jimi: All is By My Side, which is being released this fall, and the just-released Jersey Boys. But the movie I found myself thinking about the most actually wasn’t a narrative feature at all – it was the documentary Leave the World Behind, about the farewell tour and disbanding of Swedish House Mafia. As I wrote in my review, what made that film special was that although it was clearly meant for fans, it found a way to comment on ideas which were much more broadly relatable. You didn’t have to know the band to comprehend their undulation between unfettered joy and oppressive melancholy, and their search for permanence in a world of transience. I got to thinking about this because Get on Up is clearly searching for something similar. It tells the life story of James Brown, but it’s also trying to communicate why the story of the man is worth telling, and not just why his music is worth listening to.

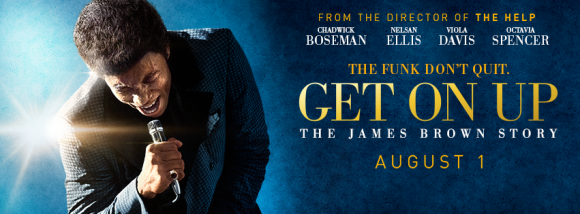

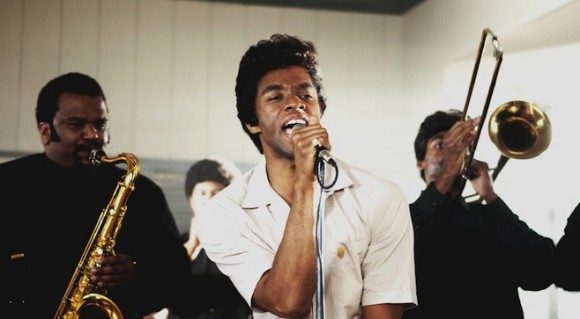

So the overall vision is there, and I suppose you’d expect it to be in a movie directed by Tate Taylor (The Help) and written by Jez and John-Henry Butterworth (Fair Game, Edge of Tomorrow), despite the limited credits for all three. And the film gets there – mostly – but it’s never quite the smooth ride you’d hope for. For one, Get on Up co-opts Jersey Boys’ decision to intermittently talk directly to camera, albeit less extensively and less obnoxiously. In a scene near the top of the film, the camera slowly zooms in on Brown (played with verve by Chadwick Boseman, 42) as he speaks to a room of people. Ostensibly he’s speaking to a woman just behind and to the right of camera, and it produces a clever effect of Brown addressing the camera without actually breaking the fourth wall – until he unquestionably does look directly at the camera and the illusion (which the film never intended to maintain) is broken. Too bad, because that could have been a fantastic effect, and the intentional addresses, some of which are far more lengthy than a sidelong glance, are a persistent and unnecessary annoyance.

Where the film really tries to build its big ideas are in the intermittent cuts from an elderly Brown to his younger self (including, most importantly, his childhood self). (And I’ll grant that this was perhaps where the filmmakers thought self-awareness might prove effective, but the film is easy enough to follow without cues beyond the date markers that appear on screen at each change.) The purpose of the temporal hopscotch is to highlight two contrasting ideas growing out of Brown’s life story – that Brown has always had to be self-sufficient, which has been a key element in his success, and that he has also always received help from others in his life, no matter how much he’d like to deny it. The truth, of course, is that both were essential, and the fact that the central theme of the movie, however powerful it may be, can be so easily summarized is why Get on Up falls short of any true greatness.

Which isn’t to say that there’s not a lot to like. It’s worth saying again that Boseman is fantastic as Brown, given much more to do here than he ever was in 42, and the supporting cast is strong as well. Nelsan Ellis plays Brown’s reserved lifelong friend Bobby Byrd, while Dan Aykroyd shows he’s still got chops as manager Ben Bart. The music is as fantastic and energetic as you’d have hoped, and watching Boseman-as-Brown perform is transfixing. In fact, it could be said that even a little too much of the film become a concert video, and if you’re not a funk fan, (well, first, what’s wrong with you?) but the extended musical sequences could certainly a drag. Due to some questionable plotting decisions, the film does seem to run a bit long as a whole, but for the most part these frayed plot lines, like an elder Brown fleeing the police for reasons that aren’t ever clear or a brief fixation on a backup singer that never figures into the larger plot, can be excused as trying to paint a complete picture of a star’s adventure through life or more simply overlooked in favor of the movie’s better parts.

The Verdict: 3 out of 5

As far as Tate Taylor movies go, The Help is clearly the superior picture. That said, both the director’s vision and technical ability are again on display in Get on Up. Also proving he’s here to stay is Chadwick Boseman, who might have stolen the show as James Brown if not for the strong performances all around him. Get on Up never quite lives up to its aspirations as a film with transcendent purpose, but it certainly does enough to justify its existence, making James Brown’s story one which was worth telling on the big screen. And, oh yeah, his music is still fantastic.