A family is reunited after a tragedy in August: Osage County, a film adapted from the Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award winning play by Tracy Letts. Those familiar with the oeuvre of Mr. Letts are surely aware that the playwright is uninterested in making his audience feel warm and fuzzy. This is the author, after all, behind such dark works as the claustrophobic paranoia thriller Bug and the salacious crime noir Killer Joe, both of which were previously adapted for the screen by William Friedkin. While the set pieces of August: Osage County aren’t so unsavory as either Bug or Killer Joe, the characters are just as, if not more, unnerving, deranged and downright vicious. August: Osage County is hardly a soft and cuddly holiday lark; it’s a darkly comic war zone in which no character is spared and no lessons are learned. You really can’t go home again, and Letts suggests that the only ways to escape the claws of family are to run as far away as possible or resolve oneself to a life steeped in misery, decay and secrecy.

Osage County, Oklahoma plays host to the small plains town where we meet the Weston clan, led by Violet Weston (Meryl Streep). Violet is an over-sized personality, a depraved and starkly cruel character, one who perhaps slipped into self parody decades ago without even realizing it. Her biting tongue, matched (ironically) with the agonizing pain of her mouth cancer, is the centerpiece of the movie, and Streep devours the part like a Southern Gothic Godzilla. Even though the film opens with a pensive Sam Shepard (who plays Violet’s poet husband Beverly) thoughtfully reciting T.S. Eliot, the quiet is soon shattered by Violet. It’s almost hard to fault Beverly for offing himself, the event which launches the story into its subsequent plate-throwing glory, a parade of big, showy scenes acted to the hilt by an all star ensemble.

The original play ran over three hours in length, and Letts, who has also written this film adaptation, is forced to truncate the proceedings into the more manageable length of two hours while trying not to dilute anything. The result often times reads like a highlight reel, but still illuminates what a grand stroke of American theater this certainly could be. Letts’s command of biting and snappish dialogue is straight from the school of luminaries like Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller, and Edward Albee, and Letts makes the dialogue-heavy story painfully and humorously personal.

Director John Wells, a titan in television with hits like The West Wing and ER, but a relative novice to directing feature films, keeps the ship running on course, and in the best segments of the film he appropriately takes a step back and lets the tremendous talents of his actors take center stage. Wells makes the Weston house (the family that is the subject of the movie) like a decaying catacomb into which light barely seeps, creating a warped and claustrophobic house of horrors for the characters to play out their savage drama. Think of it a special season of American Horror Story if it were presented by Norman Rockwell.

Following Beverly’s suicide, the extended Weston clan come swiftly to Violet’s aid. Sister Mattie Fay (Margo Martindale) comes with her husband “Big” Charlie (Chris Cooper). Violet’s eldest daughter Barbara (Julia Roberts), who left home as soon as possible, arrives with her estranged husband Bill (Ewan McGregor) and sullen, pot-smoking teenage daughter Jean (Abigail Breslin). Karen (Juliette Lewis), the flighty exasperating pixie who escaped Osage County into the arms of seemingly many ne’er-do-well suitors, brings along her slick and slimy current fiancée, Steve (Dermot Mulroney), whom Barbara swiftly writes off as “this year’s man.” Youngest daughter Ivy (Julianne Nicholson) is the lone Weston offspring who stayed home, a fragile woman who no doubt owes much of her timidity to her lifelong proximity to Violet’s wrath. “Little” Charlie (Benedict Cumberbatch), Mattie Fay and “Big” Charlie’s sweetly dim son joins the fray as well. All members lay out their own particular sets of baggage and a myriad of subplots.

The biggest hurdle for the film is that throughout nearly its entire running time, there’s little time to breathe or soak in what’s actually happening. Wells and Letts stage (an appropriate word if ever there was one) each big scene after one another as all the characters and their messy, miserable lives start to unravel. The zenith of the entire piece is an elongated dinner sequence where nearly all dirty laundry of is pulled to the surface. It’s a dizzying, demented centerpiece of a sequence, one so simplistic in its set-up, but layered with twists and forceful verbal brutality. Streep anchors the scene with the gravitas you’d expect from arguably the greatest actor of her generation, but the entire ensemble is manages to keep up with Violet’s drug and alcohol induced ranting. It’s a fitting peak, but unfortunately also one that takes place only halfway through the picture, and August: Osage County shoots off to the next big scene as soon as it’s over.

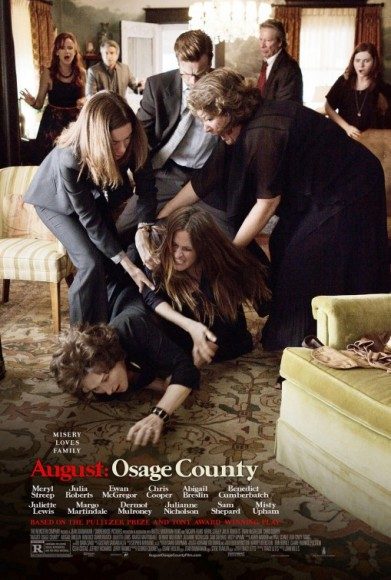

Although the film spends plenty of time with its extended cast, the prime focus is undoubtedly a talky grudge match between Violet and Barbara. Barbara scoffs at her mother’s cruelty, unaware she’s capable of the same wrathful scorn, and her own strained relationship with Jean suggests the apple doesn’t fall from the tree. Amidst all the yelling, there’s a quietly moving arc, as Violet and Barbara come across two sides of the very same coin thanks to a beautifully modulated performance on Roberts’s part. The head-to-head battles between mother and daughter are chief among the film’s highlights and the actresses mercilessly tackle (sometimes literally) one another with a heedless abandon. Yet even with Violet’s fluctuating lucidity and Barbara’s stubborn chilliness, there’s a reassuring sense that both mother and daughter actually do get through to one another. August: Osage County isn’t interested in cuddly affirmations, and Violet is as mean as Barbara is bitter, but the performances are enlivened with a sense of history and quietly tucked away warmth. After that terrible family dinner where Violet’s drug abuse is called out, Barbara tackles Violet, steals her pills and proclaims, “I’m in charge now.” It’s an moment of built up anger, resentment, but encompassed in the refrain is the idea that Violet and Barbara are both alpha mama bears who will do anything in the name of family.

To their credit, neither Letts nor Wells lets the characters off the hook by tidying up their messy lives and soured relationships with a sense of manufactured clarity. In truth, there’s no easy conclusion, and the actors beautifully carry out this vision. That being said, there are more than a few awkward narrative hiccups along the way, some of which may be because of Wells’ inexperience in shepherding such a big, sprawling piece. More than of few of the subplots arise only to devolve with a thud. The storyline tries to give every member of the cast at least one big, showy scene but often this only feels like it stretches the plot thin, diminishing some of its overall emotional potential.

More than that, though, Wells’s navigation through this family reunion from hell can’t quite lose its staged feeling. This is especially true in the few scenes set outside the Weston house which are awkward and distracting, even with the sun-drenched real Osage County as a backdrop. Nearly ever attempt to “open” the film up feels like tacked on, reminding the audience viscerally that this started out as a story confined to the square footage of a single stage. For instance, there’s one scene where Barbara screams and hollers at Violet’s doctor in his office that comes across both phony and unneccessary.

Yet in spite of all the structural issues, most can be forgiven given the strength of the performances. There’s a joy and zesty delight in watching such seasoned pros attacking Letts’s fierce, harsh dialogue and characters. That is, up until the final scene which may leave the audience, and certainly left me, with only disquieting detachment. The ending of August: Osage County has been a bit controversial among fans of the play, and while I have not seen the play myself, the movie does play as a focus group tested tack-on set to leave its audience with a sense of catharsis. The problem is, this isn’t that kind of film, and for a project that so forcefully disagrees with the notion that a happy ending is possible, it rings completely false.

The Verdict: 3 out of 5

The impeccable performances of the sprawling ensemble cast – Streep and Roberts are terrific, and I was particularly impressed with the quiet vulnerability of Julianne Nicholson’s performance – are enough to recommend the film. The whole that surrounds it is a bit more messy in its execution, with multiple subplot threads left dangling and the full impact of the Weston family feud somewhat diluted. August: Osage County, with its nasty verbal bon mots and icy stingers, recalls the scathing characterization and caustic humor in Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, but it needed a filmmaker with a clearer vision and more hands-on approach than John Wells ever provides to craft something similarly memorable.