The comparisons between Fury, the new WWII movie from writer/director David Ayer (End of Watch), and Steven Spielberg’s classic Saving Private Ryan are going to be inescapable, and not just because Spielberg’s creation is the seminal WWII movie to which all others in this modern era are inevitably compared. Fury not only duplicates the squad setup and its capable, enigmatic leader (Brad Pitt stepping in for Tom Hanks and proving every bit as capable), but captures the extreme violence of war in a way that, like its predecessor, comments on the grotesqueness of a man killing another man rather than merely serving up gore for its own sake. Fury may not make it quite to the level of Saving Private Ryan as a whole, but it’s a worthy effort in its own right that adds to the narrative of war’s horrors instead of merely rehashing old refrains.

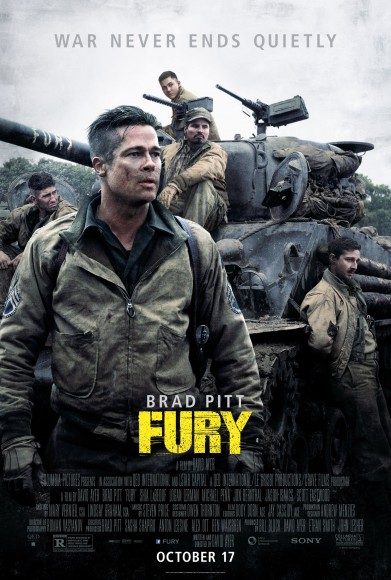

“Fury” is the name of the Sherman tank captained by Don “Wardaddy” Collier (Brad Pitt), and Fury follows him and his crew in the waning days of WWII as the Allies slowly advance across Germany. Principal among this crew is his new assistant driver/front machine gunner, a green Army clerk named Norman (Logan Lerman) pressed into service and unprepared for the horrors the rest of the crew have long endured already. At its core, this is Pitt’s and Lerman’s show, and both actors acquit themselves admirably. Those who were concerned that Pitt might become a platitude-spilling self-parody need not worry; there’s an element of that here, but it’s fatherly in nature and couched in sufficient nuance. Lerman, meanwhile, continues to show himself more than capable. If he never quite matches Pitt’s presence, it’s only because his character is necessarily more reserved. As for the rest of the crew, “Gordo” (Michael Pena) serves as the tank’s driver, with the evangelical “Bible” (Shia LaBeouf) as its gunner and the crude hick “Coon-Ass” (Jon Berenthal) as the reloader, and all three do a fine job.

The tank is part of a dwindling armored division, “outgunned and out-armored” (as we are told in introductory text at the head of the film) by the superior German machines. But Wardaddy has kept the crew safe through more than three years of combat, and they continue to forge ahead as part of the allied offensive. This is about as much of a high-level plot as there is in the movie. If you’ve seen the trailer, you know that Fury is eventually tasked with holding a road against a Nazi division, but this is really just the setup for the climax. There’s plenty of action in the movie, but is elevated by having thematic relevance to match.

Unlike Saving Private Ryan, which explored the effect of war on individual men, Fury casts its eye upon mankind at large. The members of the crew have personalities, but they, and especially the rookie Norman, are stand-ins for capital-“M” Man. Fury is most interested in exploring Man’s cruelty to himself, and especially as driven by warfare, not to mention the monstrous contraptions He has made to wage war on himself. The tank itself is a constant metaphor for this idea, although among the many sequences that comment on the destructive power of warfare technology, the one that’s stuck with me the most since seeing the movie actually has nothing to do with tanks. While driving down the road, Norman and the rest of the crew look up into a blue sky, the frame of the shot curtained with clouds. It’s a idyllic image we’ve seen often enough in films of all types – the weary protagonist looking to the peace of the heavens for respite and rejuvenation. Except that Fury never gives us that image. Norman looks up because he hears the hum of distant engines, and sees the smoke trails from airplanes on a bombing run too numerous to count. Peace is nowhere in war; there is only hate.

Time and again, Fury beats its audience down with the inescapable drive, even necessity, to hate the enemy. For the crew of the Fury, Norman soon learns, the war is personal. It is not some grand tragedy ordered by others that they may disconnect from with a sense of “doing one’s duty.” To survive, they must crave blood, and it’s easy enough to see this as the only means of sanity to their tired and tortured eyes. It’s absolutely brutal, and brutally effective.

But to its credit, Fury does not erase all hope of peace, and it’s not just Norman leading the charge. Around the midpoint of the movie finds the Fury and its battalion in possession of a newly liberated town, and Norman and Wardaddy (who speaks German, and though this is more of a plot convenience than a meaningful characterization, it nonetheless hints at untold significance) are clearing a building when they come across two German women. The women are understandably frightened, but Wardaddy and Norman are kind, and the four of them settle down to an afternoon that’s almost domestic, almost normal. Particularly with Norman and the younger of the two women, there’s a hopefulness for the future, but even in Wardaddy, there’s an unexpected pacifism and respectability. He wants this war over as much as anyone. The film is never cheerful, and does return to plumb all the deeper the depths of hate, but this interlude (though overlong) is a welcome counterbalance that gives the movie a nuance it would otherwise be lacking.

Fury does find its faults, however; the first half of the movie is definitely stronger than the second half, and Norman’s transformation from a pacifistic, scared-shitless greenhorn to a gleeful murderer is a little overdone. Norman’s arc is necessary in a movie that’s all about contextualizing the descent into human depravity that war incurs, but the movie is weakest at a few plot points that are needed to drive this story as that exemplar of the war at large.

The Verdict: 4 out of 5

David Ayer has created a movie that invites comparison with the best in its genre and would deserve to stand among those films were its second half as thematically complex as its first half. Still, helped along by strong performances across the board, Fury is more than a mere war film; it’s a film that captures the utter destructiveness of war in terms both of technological capability and of psychological devastation. War breeds hate, and Fury is appropriately brutal in describing this causal relationship.