Time travel is like the bullied kid of sci-fi film concepts, wouldn’t you say? It’s this weird subgenre of science fiction that people go in fully prepared to rip the rules and mechanics apart. It’s probably the most egregious task a screenwriter can be assigned is to be told to write a time travel story—because, in this instance, screenplays are dispersed like book reports, apparently—and have the added unenviable task of having clearly defined rules and story details that don’t contradict each other. And big shock, it never works. There will always be those who, whether they mean to or not, have their brains pick apart the minutiae of everything, and, like a psychopath who uses red strings to connect notes to photos to prove connections in a conspiracy, they’ll invariably find reasons that one thing contradicts another.

One of the biggest hurdles that befall most of those stories is they often revolve around going to the past and how that impacts the future, and in doing that, they always welcome themselves to scrutiny. They’re opening a can of worms—a can of time worms, if you will (but you don’t have to). There are things like the butterfly effect, multiple timelines, and the current future becoming the past, which can’t be changed because of the former—you know what? This isn’t an expository Doc Brown/Professor Hulk scene; you know all the annoying details that make talking about time travel exhausting, and we’re working on a maximum word count cutoff point here.

The point that we’re oh-so steadily getting to—this is a marathon, not a hundred-meter dash—is time travel movies would fall under less prying eyes of critical flaw-finding film fanatics—that’s a quadruple alliterative, eat your heart out, Sam Wanamaker—is if, rather than going into the past, they went into the future and in doing so, allowing the stories not to be tied down so fiercely by the complexities that come about from how the past could change the future, while still maintaining the fish-out-of-water fun that comes from characters being in a completely different era. The film that makes a compelling case for this is the 1979 film Time After Time.

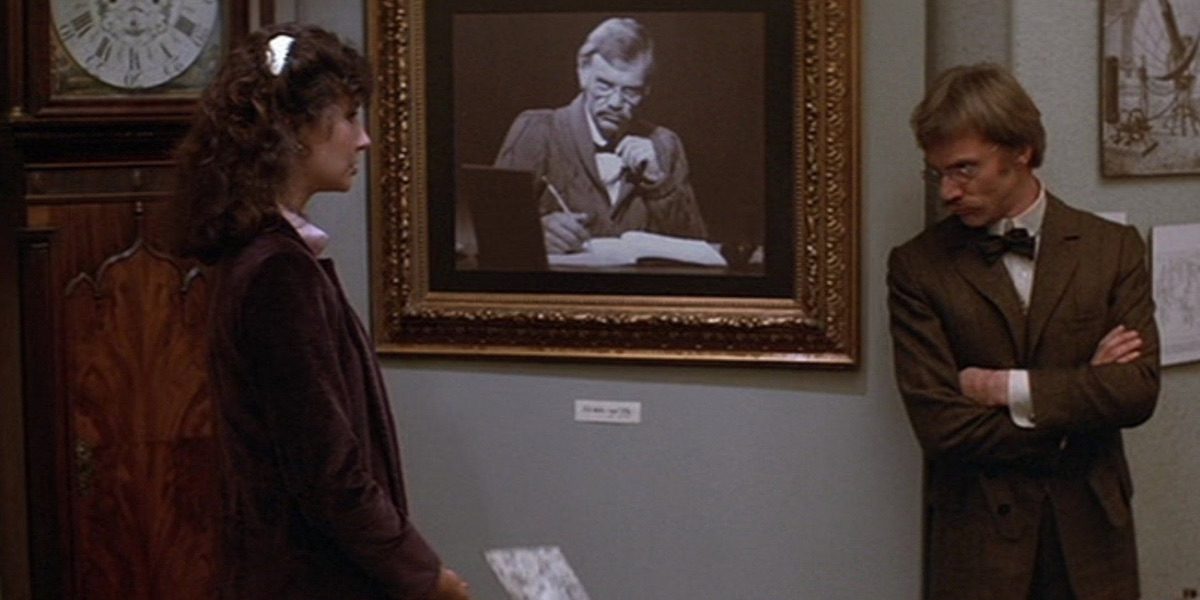

If you haven’t seen it, the film takes place in a revisionist history of London in 1893, where the writer H.G. Wells (Malcolm McDowell) has created a functioning time machine and is also unaware that his friend John Stevenson (David Warner) is actually Jack The Ripper. With the authorities closing in on him, John steals the time machine to escape into the future. In pursuit to bring John back to their time and to face justice, Wells finds himself in San Francisco in the 1970s. Once there, Wells also develops a romance with an American woman named Amy, played by Mary Steenburgen. Because, much like Rachel McAdams, Steenburgen has an affinity to get wrapped up with time travelers.

Time travel movies, with the exception of Back to the Future: Part II, rarely go into the future. More often than not, the stories revolve around the lead characters going into the past to change the present, or it ultimately just happens as an aside to inadvertently assemble the eggs, sugar, flour, and milk, which, by the time they get back, will have become cake in which they’ll have their icing on. You have direct resolutions and answers to whether things get changed. There’s no plausible deniability, and nothing left up in the air, which leads to people talking about how time travel really works, even though it doesn’t exist. Time After Time actively avoids all of that—for the most part—because the time travel element is just a framing device to make the story happen rather than revolving around time travel. It’s comparable to something like Reservoir Dogs, which is a movie about a heist, but you wouldn’t put it in the same category of heist films as something along the lines of Ocean’s Eleven.

The film also gracefully sidesteps the protagonist having high-minded principles about changing the flow of history. H.G.—you know what, we’re going to call him Herbert from here on out; first names consisting of initials are annoying, and the grammatical debate of whether to use one or two periods is not worth the trouble. Anyway, Herbert doesn’t have some temporal prime directive/non-interference rule about not changing the future. His purpose in building the time machine was to go into the future and witness how polite and civilized the world would become (cue the Curb Your Enthusiasm theme). It was just a project he was working on in the same way Kiernan Shipka’s friend just happens to be making a time machine as a science fair project in Totally Killer or that time Tony Stark proved time travel was possible after a sad bout of dishwashing—hey, remember when building time machines in movies was considered an accomplishment? Why has it become something that people do in their spare time?

His interests weren’t to alter anything but to bask in the glow of how far civilization would advance. When he goes after John, his motivation is to stop him from killing anybody else. Herbert could care less about future events being altered, so much so that when Amy is at risk of being Jack’s next victim, Herbert is fully willing to do what Doc Brown wouldn’t and take Mary Steenburgen back to his time and just bail, which is what ends up happening after they win anyway. Just a total disregard for altering the future, but screw it; it’s a proper Hollywood happy ending. He doesn’t care, so why should we?

The mechanics of how time travel works are glossed over, too. There’s no artifact that morphs throughout the story to imply whether history (or future history) is altered, like the photograph in Back to the Future, and there’s no expository moment of Herbert in front of a chalkboard explaining his theory on how time travel would function. That’s all for the best because time travel as a concept is so complex and often contradicting that, ironically, the more it’s explained, the more it brings to light details that could potentially not add up, so pulling that thread doesn’t do anyone any favors. As Abe (Jeff Daniels) from Looper puts it so succinctly, “This time travel sh*t fries your brain like an egg. Why the f*ck, French?” Alright, maybe the second part doesn’t factor in without context, but you get the idea.

There’s an internal logic that the movie operates on, but it never throws in any monkey wrenches that could complicate things. Nobody runs into younger or older versions of themselves; there are no causality loops or paradoxes. It strips all of that away, and when it does something wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey, it doesn’t dwell on it. Herbert and Amy go a few days into the future and find a newspaper, which is how they learn Amy is going to get murdered. After that newspaper has served its function in the plot, it just goes away. Does it disappear when the events within the paper change? Does the physical paper continue to exist, but the contents change? Feel free to theorize because the movie never reveals what would happen.

The film also avoids the recurring trope of a malfunctioning time machine. Since the existence of a time machine negates the relevance of having a “ticking clock” element, one of the most common methods to create drama is to have the machine not work or create minimal windows of opportunity to use it. That is unless you’re Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, in which case all time everywhere is linear and happening at the exact same time…yeah, sure, alright. But more often than not, this leads to a short window to operate. Lightning striking the clock tower at 10:04 pm, you need the Chernobly poured in the hot tub because the party is over before dawn, the Necronomicon holds the key, go to a dark place and clench your fists really tight, you know, those sort of things.

Time After Time steers clear of all of that. The time machine is effectively parked in an H.G. Wells exhibit, Herbert has the key, and it never has any technical problems. Do you know how jarring it is to see a movie where a time machine has no defects and no fine print on the terms of use? It’s like seeing a live-action Spiderman movie where Peter Parker doesn’t cry onscreen—it’s so rare that when it doesn’t happen, it’s weirdly refreshing. Time travelers can occasionally be competent at building things, and Captain America: Civil War doesn’t have any story beats that necessitate Tom Holland’s tear ducts to be overworked and, by extension, have tears flood his cheeks without him wiping them away. Seriously, Movie People—or actors, whatever the preferred nomenclature is—just wipe away the tears. Do you know how uncomfortable it is to have tears tickle the bottom of your jaw because you didn’t wipe them away? Who benefits from that?

Just a brief aside while we’re wrapping up here: have you ever noticed the little details connecting this film to Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home? The better question is, have you seen either? If not…well, thanks for sticking around this long. Time After Time was written and directed by Nicholas Meyer, who directed Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan and was also involved in doing some rewrite work for Star Trek IV. In many ways, this film works almost like a proof of concept for the latter.

There are little things like both films taking place in San Francisco, the lead characters going so far into a different time period—forward for Time After Time, backward for Star Trek IV—that they’re out of their element of how things work, which lends itself to genuinely clever fish out of water comedic moments. Both have scenes in pawn shops where the characters sell an antique to make some quick money. Time travel is depicted as super abstract with crazy visuals. There’s even a soapbox scene where both movies stop their stories dead to have social commentary about modern-day society. To sum up, Time After Time tells us that our culture is violence-obsessed, and Star Trek IV reminds us that whaling is wrong.

Both movies also have the lead character get romantically involved with a woman of the period, ultimately bringing them along at the end with absolutely zero regard for how it’ll affect history. The main difference is that Herbert gets to marry Amy, and Kirk only gets an awkward cheek kiss from Gillian. Welcome to the friend zone, Kirk. It’s like the Neutral Zone, except instead of being unable to enter it, you never get to leave it. It all ended up being for the best; word on the street is Gillian had big eyes for Captain Decker.

(Writer’s Note: Yes, Nerds, we know Decker had already merged with V’Ger at that point, so continuity-wise, that reference doesn’t make sense, but you’ve got to stir the pot of 7th Heaven fan theories somehow.)

What have we learned today? A lot of unsolicited trivia about Star Trek, for one thing. Bet you weren’t expecting that for an article revolving around an underseen time travel film from the late 70s. But for real, though, the message is to…you know, not harp on time travel movies that much; writing movies is hard, and writing time travel movies is even harder. Probably. Never tried it. To be honest, we kind of buried the lead a bit, so if you want some overarching message about how Time After Time is the be-all and end-all of time travel movies, it’s probably in there somewhere. But hey, all of Hollywood, since we have your attention, implement going into the future more for your time travel stories. Movies don’t do it that often, and you could save yourself a lot of trouble from people arguing about the rules of time travel on the internet. To once again quote Abe from Looper: just be new.