When it comes to cinematic reboots, Spider-Man and Batman might come to mind as some of the characters who have been reimagined on the big screen more times than any other. But in fact, one of the most obvious victims of Hollywood’s reboot obsession is a character whose history can be traced back more than 170 years – Ebenezer Scrooge.

Since his creation in Charles Dickens’ 1843 novella A Christmas Carol, fiction’s most famous holiday grouch has been portrayed dozens of times in various screen adaptations of the classic story. While most interpretations follow the general format of a selfish curmudgeon who changes his ways after being visited by a group of ghostly spirits, several have altered the setting, time period, and details of the iconic tale in order to offer a unique experience that stands apart from other versions. The result has been a wide range of Scrooges and Scrooge-like characters in cinema.

The latest iteration, played by Christopher Plummer in The Man Who Invented Christmas, which opened last week, pitches the character as a figment of Dickens’ imagination who was based on the author’s own father. The debut of this new interpretation of Scrooge offers an interesting opportunity to look back at several of the Ebenezers who have come and gone through the years, exploring the wildly diverse ways in which the character has been represented over the course of movie history.

The first instance of Scrooge appearing onscreen dates back to 1910, when Australian actor Marc McDermott starred in a 17-minute silent version of A Christmas Carol. A long string of early film and radio adaptations of the story followed. During this period, Scrooge was played by such legendary actors as Lionel and John Barrymore, Orson Welles, Claude Rains, and Basil Rathbone.

1958 marked an important moment for the character with the release of actor and advertising director Stan Freberg’s comedy record Green Chri$tma$. For the first time, Scrooge transcended his role as merely a literary character and served as a biting commentary on the modern concept of Christmas as a whole, along with American consumerism.

The record tells the story of a “Mr. Scrooge” (voiced by Freberg himself), the head of an advertising agency, who gathers his clients to convince them to theme their products to the Christmas season in order to increase sales. Bob Cratchit, a client whose name derives from another Christmas Carol character, would prefer to send Christmas cards celebrating good will toward men and peace on Earth, but Scrooge cautions against this and encourages profiting off of Christmas.

The record’s incendiary, anti-commercialism message upset many in the advertising industry, and Capitol Records at first refused to release it. But most Americans appreciated the piece’s honesty and humorous satire, which helped to launch Freberg’s career.

Green Chri$tma$ was to be the first of many instances of the Ebenezer Scrooge character being repurposed to send a specific message about modern life. A few years later, in 1964, The Twilight Zone creator Rod Serling wrote a television film entitled A Carol for Another Christmas, which modernized the Dickens classic to promote the United Nations, while also reinterpreting its Scrooge character as a wealthy American industrialist and isolationist whose nephew attempts to convince him of the value of global cooperation and diplomacy.

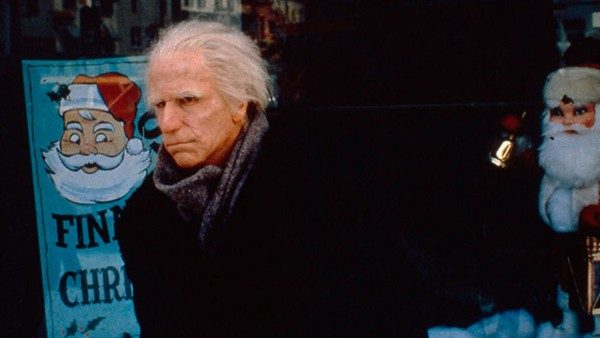

Scrooge was again Americanized in the 1979 television movie An American Christmas Carol, which starred Henry Winkler as Depression-era New England businessman Benedict Slade. In a curious coincidence, Academy Award-winning makeup artist Rick Baker, who contributed to Winkler’s aging makeup in the film, would later work on the extensive makeup for Dr. Seuss’ Scrooge-inspired character the Grinch in director Ron Howard’s Dr. Seuss’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas.

Among American audiences, arguably one of the most definitive versions of Scrooge was George C. Scott’s more traditional take in the 1984 British-American production of A Christmas Carol. This film is notable for casting an American actor as Scrooge in a production populated mainly with English performers.

1988 brought one of the most blatantly comedic takes on A Christmas Carol in the form of Scrooged, a modernization of the story starring Bill Murray. In this film, Murray plays Frank Cross, the selfish head of a television network who forces his staff to work on Christmas Eve in order to mount a live production of A Christmas Carol.

The film reimagines the Ghost of Christmas Past as a taxi driver, the Ghost of Christmas Present as a vivacious pixie, and the Ghost of Christmas Future as a robed skeleton with a television for a head. While Murray’s Cross is clearly the Scrooge-ish lead in the story, the movie also features veteran comedy actor Buddy Hackett playing Ebenezer in the Christmas Carol live production staged by Cross’ team.

Scrooged thus served to both modernize Dickens’ story and satirize the very practice of churning out modern remakes of the holiday classic. Cross’ live production of A Christmas Carol features scantily-clad dancers and a terrifying, explosion-filled television ad. In a sense, it serves as a meta-criticism of the desperation of film and television executives who constantly feel the need to cash in on classic stories while also forcing modern elements into their adaptations in order to make these stories feel “relevant,” thereby tarnishing the very source material they claim to worship.

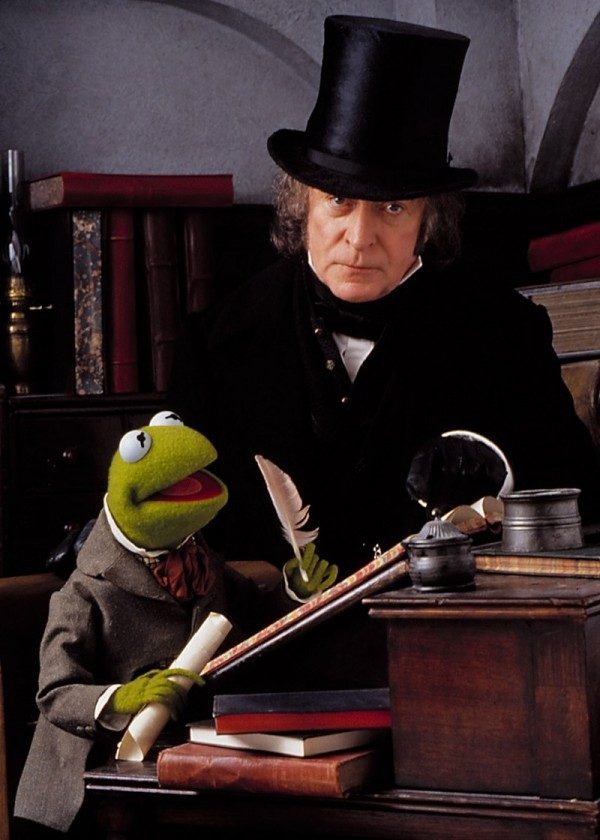

Michael Caine seemed to have learned this very lesson by the time he signed on to play Scrooge in 1992. Caine joined the cast of The Muppet Christmas Carol, a kid-friendly adaptation starring puppeteer and filmmaker Jim Henson’s beloved Muppet characters. The film was the first Muppet movie produced without Henson, following his death in 1990. As a result, Henson’s son Brian directed after selling the script to Walt Disney Pictures, making it the first of many Disney-produced Muppet films.

Caine was approached to play Scrooge (one of the only human characters in a film populated primarily with puppets), and he reportedly agreed on one condition: that he would play the character as if he were working with the Royal Shakespeare Company, delivering a totally straight, dramatic performance as though surrounded by actual humans and not felt puppets. He was even quoted as saying, “I will never wink, I will never do anything Muppety.”

Caine’s serious approach to the character, while perhaps odd in a Muppet film, offered a welcome respite from the overly-hammy, self-referential modern interpretations of Scrooge seen in several adaptations throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

Interestingly, much of the film’s humor ultimately derives from the contrast between Caine’s dramatic, unironic performance and the colorful, fantastical characters around him. It’s hard not to laugh while watching Scrooge scowl and calmly lecture Kermit the Frog’s Bob Cratchit on the finer points of the moneylending industry.

Beyond this, Caine’s seriousness also serves to legitimize the Muppets themselves. As funny as it is to see Kermit get chewed out by Caine’s Scrooge, we genuinely sympathize with the frog’s plight as Ebenezer’s underpaid and underappreciated underling, despite the fact that the character is an amphibian made of green fabric.

As Jim Henson knew, the Muppets are at their funniest when interacting with human performers who treat them as real beings. This approach transforms them from soulless puppets into believable and memorable characters who are every bit as real as the people with whom they perform. Frequent Muppet collaborators like Jimmy Dean and Steve Martin knew this, and their performances helped to propel the characters to the stardom they know today.

Caine’s performance followed suit, helping to establish The Muppet Christmas Carol as one of the most genuinely heartwarming and affecting Muppet productions ever, launching a relationship between the iconic puppets and Walt Disney Pictures that continues to this day.

This movie was also memorable for including Charles Dickens in the story, functioning as the narrator and played by the Muppet Gonzo. This strategy would later be used in other versions of A Christmas Carol.

The 1990s and early 2000s saw their fare share of Christmas Carol adaptations, including several female-led versions. A Diva’s Christmas Carol starred Vanessa Williams as cold-hearted pop singer Ebony Scrooge, and 2003’s A Carol Christmas starred Tori Spelling as an arrogant talk show host, bearing many plot similarities to Scrooged.

2009’s Ghosts of Girlfriends Past combined the Christmas Carol formula with a Matthew McConaughey romantic comedy, to disappointing results. The movie is a classic example of an overly-corny and unnecessary modernization of Dickens’ story, featuring McConaughey as a self-centered womanizer who is visited by ghosts who show him the past, present and future of his romantic life, ultimately leading him to reconnect with the only girl he has ever truly loved. The film exists today only as an unpleasant reminder of the types of formulaic, stereotypical rom-coms McConaughey became known for before branching out into complex, critically-acclaimed performances.

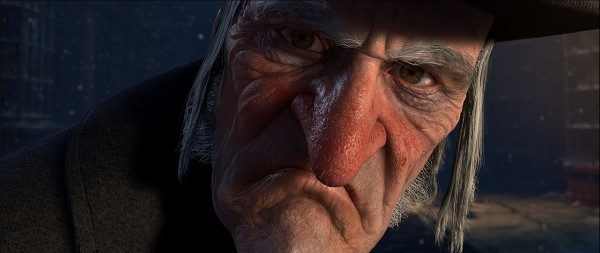

Next up was writer-director Robert Zemeckis’ 2009 computer-animated motion-capture adaptation of A Christmas Carol, which stood out for several reasons. The Walt Disney Pictures-produced movie stuck particularly closely to Dickens’ original novella, lifting exact dialogue from the text and even mimicking the artwork of John Leech, who drew the original illustrations featured in the book’s first edition. The film also featured a star-studded cast including Jim Carrey, Gary Oldman, Robin Wright, Colin Firth, and Cary Elwes.

The use of motion-capture technology allowed some of the actors to portray multiple roles. For instance, Carrey played Scrooge along with all three ghosts, and Oldman portrayed Bob Cratchit, Cratchit’s son Tiny Tim, and Scrooge’s former colleague Jacob Marley. While Carrey had previously delivered a comedic interpretation of the Scrooge-influenced Dr. Seuss character the Grinch in 2000, his turn as Ebenezer Scrooge came across as much darker and more serious. Carrey stated that he worked hard to perfect his English accent and to achieve a unique physical presence for Scrooge and each of the ghosts, hoping to create a film that would be warmly accepted in the U.K.

While the authenticity of the film was appreciated, its darker tone was criticized by many who thought that a Disney interpretation of the story should be more child-friendly. Perhaps as a result, adaptations of A Christmas Carol in the years immediately following this version tended toward the lighter side, such as George Lopez’s performance as Scrooge stand-in Grouchy Smurf in The Smurfs: A Christmas Carol.

Now, we seem to have reached a point where a solemn respect for Dickens’ original vision and the desire to capture a lighthearted, modern energy have met. The Man Who Invented Christmas represents the clash, or perhaps the coalition, between these two approaches.

Rather than a straight adaptation of A Christmas Carol, this movie functions as a historical re-telling of the process Dickens undertook to write his famous novella. The plot follows a young Dickens, played by Dan Stevens, fresh off of the failure of his past three novels and eager for a hit that will sustain his family and his withering career. Over the course of six weeks, Dickens takes inspiration from real-life individuals around him and concocts the plot and characters of A Christmas Carol. In the process, he helps to establish the modern concept of Christmas itself.

Since the movie obviously stands apart from previous films by focusing on Dickens rather than his novella, its use of Scrooge differs dramatically as well. Christopher Plummer plays a version of Ebenezer who is the personification of Dickens’ own imagination. He appears at the exact moment Dickens dreams up the name Scrooge, and begins conversing with the author as if he is actually present in the room with him, almost functioning as a ghost himself.

The movie draws similarities between Scrooge and Dickens’ father, John, suggesting that the author used his dad as inspiration for the character’s self-centered tendencies. It provides the same treatment for other Christmas Carol characters, such as Tiny Tim and Jacob Marley, who all appear in Dickens’ imagination and help to encourage him as he works through the creation of his story.

But instead of focusing on the dark tone of Scrooge’s ominous storyline, the film emphasizes Dan Stevens’ portrayal of Dickens as a vibrant, playful creative, a dreamer who lives for the thrill of concocting stories and wishes to celebrate a modern, festive, and cheerful concept of Christmas. This last part is in fact true, as Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol at a time when the British were reviving old Christmas traditions, such as carols, while also experimenting with new staples of the holiday like Christmas trees. Many credit Dickens’ novella with helping to usher in the modern Western concept of Christmas as a time to consume seasonal foods, gather with family, and celebrate generosity.

While The Man Who Invented Christmas may take some historical liberties with Dickens’ life story and creative process in the name of entertainment, it does serve as an interesting next step in the evolution of the Christmas Carol adaptation. It is nice to see old Ebenezer Scrooge portrayed as not merely the heartless miser we have seen countless times, but as an idea that saved a struggling young author and his family. There’s nothing selfish about that.