If you have been paying attention to Hollywood filmmaking lately, you will have undoubtedly noticed a certain pattern – some might even call it a glut – that has emerged in the past few years. There is a trend, particularly noticeable around the summer months, for films to have their roots in preexisting properties rather than on new material. We’ve gotten rehashes and reinterpretations of preexisting movie franchises, comic book series and graphic novels, stage musicals, video games, toy brands, amusement park rides, and more! Now, the reasons for this particular course have been debated and picked apart ad nauseam: the lure of cross-medium appeal, the fiscal security of a preexisting audience investment, the ability to easily promote and merchandise beyond the movie theater, etc. And whatever the perceived cultural cost of this trend, the combined profits of many of these films could rival the gross domestic product of medium-sized nations, so we’re not expecting any major course corrections any time soon.

For many, however, the point where the scales tip into the lands of absurd self-parody is whenever a film based on a board game is announced. 2012’s Battleship debacle is perhaps the most infamous example. The current vogue of translating board games into films is often seen as Hollywood’s adaptive addiction at its most crass and amoral. No matter how unnecessary and mercenary a film adaptation of, say, a decades-old cartoon character might seem, at least in that case the filmmakers are inheriting specific characters, scenarios, and themes to work with. Board games can only provide the suggestions of these elements – the narrative blanks that the films need to fill in are much more pronounced. And when you get a film like Battleship, which strayed far, far away from the recognizable game in the filling of those blanks, well… it becomes hard to escape the feeling that Hollywood is pursuing these properties only for the comfort blanket of preexisting appeal rather than for any creative or cultural value.

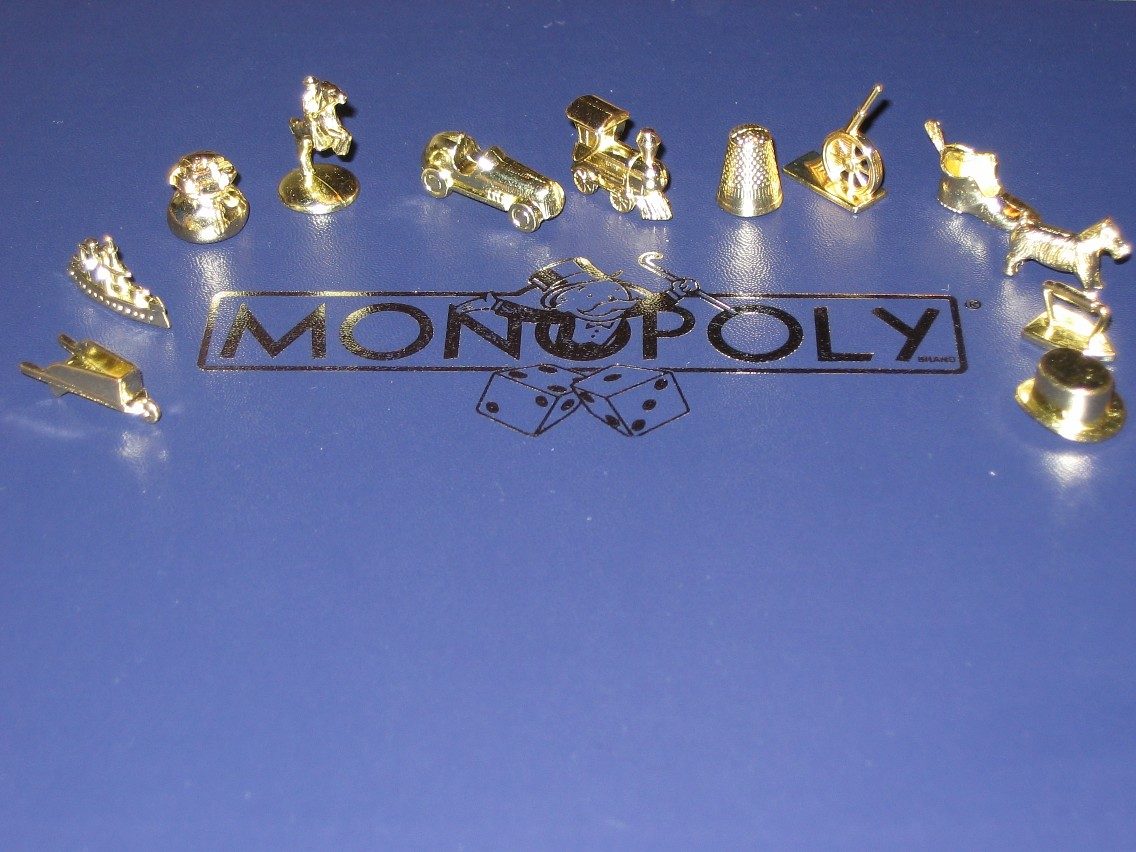

Not that these sorts of considerations have put any kind of a dent in studios’ plans to keep making movies based on board games. Over the previous years, Hasbro has announced deals for films based on everything from Hungry, Hungry Hippos to Candyland. Most recently, a few heads were turned by the unveiling of plans for Monopoly, arguably the most popular (or at least most ubiquitous) board game of the modern era, to make the leap into the silver screen. And if you are experiencing a vague sense of déjà vu, it’s because that particular announcement has been made at pretty regular intervals since 2008. Formerly set to be a Ridley Scott project, the property has undergone a few reinventions and dormant periods. This new iteration is set to be written by Andrew Niccol (writer-director of Gattaca, and Oscar-nominated screenwriter for The Truman Show) and aims to be a “a film for all ages, visually sumptuous, heartwarming, and full of action and adventure.” Between now and the moment of its inception, the film has seen a modest amount of heavy hitting writers and producers involved for some stage of development hell or other.

All of which does beg some questions… Is there something to this idea of adapting board games, aside from the ruthless calculus of bean counting? What exactly is it about Rich Uncle Pennybags and his world of cutthroat real estate that has attracted multiple Oscar-caliber filmmakers to the property? And is it possible to approach the idea of making a Monopoly movie and earning something more than huge bags of money?

Let’s start with that first question. When asked by Business Insider about the recent proliferation of board game movies, Hasbro Chief Marketing Officer John Frascotti responded:

“In the case of some of our board game titles like Ouija and Candy Land these are brands that have a lot of cross-generational relevance and cross-generational emotional appeal because parents and children have grown up playing these games and associate them with really enjoyable parts of their lives. A brand like Candy Land has such emotional resonance with moms and their daughters because it’s been played for years and it’s been a shared experience. A brand like Ouija has a certain amount of mystery and intrigue behind the brand.

“What we find is that these brands are great platforms for storytelling. So even though they may not have quite the same lore and character beneath them that Transformers and G.I. Joe do, they certainly have a high degree of emotional resonance, cross-generational resonance, and they serve as a great platform for storytelling because they involve, in the case of Candy Land, great characters in the board game, and in the case of Ouija, there’s that intrigue and mystery behind the brand that has existed for many years.”

The first half of that address is less interesting, as it stays within the realms of cross-promotional and generational appeal that gets audiences into the movie theater. It’s once Mr. Frascotti begins to address what happens to the film’s storytelling that our eyebrows rise up a bit. What’s particularly telling is the way that he phrases his statement: these properties are great platforms for storytelling, not great stories. A tiny distinction, but a telling one.

Two weeks ago we talked about the difficulties of adapting the character of Spider-Man into film form, particularly when contracts stipulate when, how, and to what effect various events have to unfold in the hero’s life. When you take on Peter Parker you’re buying an iconic costume and a particular tone of rip-roaring, crime-fighting adventures, but you’re also taking on backstories, romantic partners, aged relatives, archenemies, and setpiece moments. On its most basic level, you’re buying a series of events that occurred to a specific character in a particular sequence, and you can only deviate so much before it feels like you are doing a disservice to the source material.

But when you’re adapting a board game you don’t have that sense of a specific sequence of events; the main element that people remember from something like Monopoly or Candyland is not so much a set of events as a set of mechanics. It really is like just buying the iconic suit and the crime-fighting tone but none of the baggage. And as long as you nail those elements in the presentation, you’ve got the narrative freedom to expand outwards as necessary.

I think this is the reason why something like Clue, which was adapted into a film in 1985, is a bit more of an intuitive fit than other adaptations we’ve seen so far. Sure, the film was more of a divisive cult hit rather than a runaway box-office smash, but it’s remembered more fondly than practically anything else in this particular trend. The film perfectly captures so many of the surface details and mechanical workings of the game, and that buys it the leeway to spin the story in different directions. It helps that the source material itself has more of a sense of narrative attached to it than other games, but the film’s devotion to preserving the specific details is still remarkable. It is all set around the murder of a wealthy party host. It does follow six suspects who are trying to solve the mystery. Its main setting does follow the general pattern of the house plan that serves as the game’s board, even down to the secret passageways that transport people around the building. And, of course, murders are committed through a revolver, a wrench, a candlestick, a rope, etc. Since these recognizable elements of the game’s mechanics are on hand, the screenplay is free to go wherever it needs to in order to structure the comedy-murder-mystery. Want to make Colonel Mustard a secret war profiteer? Sounds good to us. Mrs. White is widower to both a nuclear physicist and a stage illusionist? Okay. You want to introduce a deranged butler to serve as master of ceremonies? Who’s going to tell you that you can’t do that?

It’s this same adaptive flexibility that has let the Monopoly film undergo so many skin changes since it was first announced in 2008. The original take from Ridley Scott seems to have been more of a comedic take on Wall Street, focused on the ridiculous extremes that people will pursue for the sake of money. “I wanted to just make a movie about the idea of greed. I told them you know your game can turn your sweetest, dearest aunt into a demon — a nightmare of greed. So that’s what we’re going to do,” Scott said in an interview with ComingSoon.net. Later interpretations of the film were described as a Goonies-like family adventure, complete with a treasure map, while the new Andrew Niccol-penned project seems to be taking more of a Horatio Alger approach, following, “a boy from Baltic Avenue, one of the cheapest properties in the US version of the game, who uses both Chance and Community cards to make his fortune.” And all of those are a far cry from an even older treatment of the project, by There’s Something About Mary scribe Frank Beddor, which followed a lovable loser who actually gets sucked into the game, Jumanji-style.

And some of those concepts sound like they’re destined to make better films than others, but as adaptations they’re all playing on an even field. Since they all hit those external signifiers of the games mechanics to at least some degree, it’s hard to argue that one is a more valid take on the material than the others. (Well… okay, the Goonies version of Monopoly sounds a bit more out of left field than the others, but we know next to nothing about the actual details of what it was aiming to do). Again, it sounds like such a crass money-grubbing tactic – all of the propulsive momentum of a built-in audience but with a minimum of narrative responsibility. Sure, there’s a bit of a double-edged sword in the mix due to the fact that you do have to service those recognizable mechanics from the games (and woe to the filmmakers that fail to deliver on even that basic of a level), but there is something that just feels creatively suspect about the entire thing, isn’t there there?

Well, yes… but it doesn’t have to. It’s a shame that Battleship was met with so much critical and popular reviling, because that film is the closest thing we have to a proof-of-concept of an insidious little idea that might actually deliver on board game movies’ hidden creative potential. Namely, the notion that once you’re working on a recognizable adaptation you’re free to take all manner of creative risks that would normally be completely unthinkable. Imagine you have a great idea for an alien invasion movie, something really fresh and creative that hasn’t been seen before, but nobody wants to touch it because it’s going to cost $300 million. What if you can bend that concept just far enough to include the recognizable mechanics of a recognizable board game, say… Battleship? Suddenly you’re using what seems like the safest, greediest, and most cowardly tactic in the Hollywood playbook to make something that could actually be fresh and different. After all… if there is a theoretical audience no matter what you do and you’re not boxed in by what you have to do to serve your source material, there’s almost nothing to stop you from trying something really crazy and original with your story.

Of course, that requires for you to have a phenomenal script and a deft handle on how to integrate the mechanics of the original game, neither of which director Peter Berg really seemed to have with Battleship. But the concept still stands. Sure, board game films may well be a product of mercenary Hollywood accounting, but that doesn’t mean that they can’t be hijacked into actually serving up some interesting and creative ideas. Andrew Niccol, the current torch-holder for the Monopoly film is known for some of the most sophisticated and incisive science fiction films of the past two decades… as well as for a whole bunch of wasted potential and some truly terrible literary adaptations. Let’s hope that he’s allowed to keep the subversive and provocative sensibilities that made Gattaca and The Truman Show so affecting as he translates Rich Uncle Pennybags to the big screen. The film, if it ever makes it out of jail, is likely going to make an impact in the box office no matter what happens – it’s managing to make one anywhere else that’ll be the real coup.