With a pop culture becoming increasingly dependent on nostalgia – last week alone brought us big screen re-whatevers of Power Rangers and CHIPS, as well as details on a potential Matrix cash-grab – it’s unavoidable that even some of the better works of the past couple of decades will be repurposed for our screening dollars.

Among the most recent trends is the Unwanted And Too Late Sequel – those ‘next chapters’ that come over a decade after the last installment. They might have a lot of the same behind the screens crew and returning cast, but they almost always fail. From the lowest dregs such as Dumb and Dumber To (20 years between) and Zoolander No. 2 (15 years between) to even those with the highest pedigree like Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (19 years between, though more of a soft reboot) and Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps (23 years between, and probably Oliver Stone’s lowest point)– these are the types of movies that make us hesitant to return back to the movies we loved lest we spent a good portion of our lives being wrong about taste. And, of course, this month’s T2: Trainspotting, a film so dependent on nostalgia, it stole its title from a nearly 25-year-old marketing gimmick.

To be fair, the decade-plus sequel need not always be a death knell for quality. Richard Linklater’s Before trilogy, which chronicles the relationship between two people (played by Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy) once every decade is probably his crowning achievement. Hal Hartley similarly gave us a fresh and original installments of the Henry Fool trilogy once every decade. And…is that it? But these series uniquely work because they play into the filmmakers’ evolution as an artist and as a person. The original films also never had remarkable cultural impact, so the filmmakers don’t feel as beholden to repeat what made the first installments so successful, which enables the sequels to become their own entity rather than a cheap retread.

However, for the most part, decade-plus sequels are trapped way too much in the past and are unable to develop a voice of their own. We want a sequel because we loved the original, so the past, or rather the nostalgia, naturally becomes the biggest problem with these movies – not just for the audience, but for the filmmakers.

As an audience, we are, let’s face it, not particularly discerning. We might recognize and acknowledge that what we are watching is but a pale reflection of its former self, but throw in some callbacks (no matter how horrible or clumsily done, Indiana Jones) and a decent moment here or there, and we’re willing to accept an okay-if-unexceptional movie. (Or worse…) On the whole, there’s nothing wrong with a ‘just fine’ movie, but when starting from a great movie, shouldn’t it feel like let down?

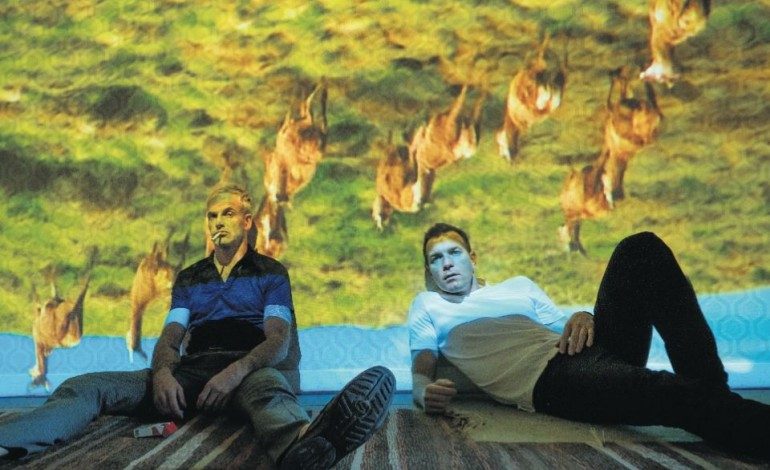

This is a particularly notable question for more adult fare, such as 1996’s Trainspotting, which skews closer in spirit to the Before and Fool series. The original film, of which I am a fan, was a dark, gritty movie about violent junkies and criminals in Scotland. A big part of its appeal came from the spirit of filmmaker Danny Boyle (working off of Irvine Welsh’s classic novel, who similarly couldn’t successfully bring back the boys in 2000’s Porno), which he shared with many auteurs of 1990s independent cinema. The angst, the anger, and the indefatigable nature of which is what gave life to Renton, Spud, and Begbie – and Vincent Vega and Dante Hicks and so many memorable characters from that period. That attitude was a major component of the films’ initial success, but that’s an attitude that is best served by the hunger of youth, regardless of decade or generation.

21 years later, that’s going to be missing. It has to be. People get older. They change. Settle down. Priorities shuffle. They look back on the past with kinder eyes because now they have a past to look back on. This softening of the edges is a fact of life that’s true for most everyone – filmmaker or not. It’s not necessarily a bad thing (though sometimes it can be; one only needs to look at Boyle’s Miramax-brother Kevin Smith, who made the moral of Clerks II that Quick Stop and RST Video are Shangri-La? If that isn’t a downer…), it’s how we grow as people, but what does it mean for this individual project? Unfortunately, it probably means that the sense of rebellion that defined the original is going to be lacking. That pissed off spirit that inspired the worst toilet in Scotland and a hallucination of a baby dead from neglect crawling on the ceiling has (hopefully) moved onto the newest crop of filmmakers.

But without that component, is Trainspotting really a world worth returning to? These aren’t “old friends” we want to return to, they’re scumbags. The first movie knew it and played towards that angle; the characters were allowed to be despised because we never expected returning to them. Coming back to them so many years later almost certainly means that they’re going to be viewed with rose-colored glasses fitted with the lenses of nostalgia and love. I can understand why Boyle and the actors would feel that way, and you can’t really fault filmmakers and stars for wanting to reminisce and try to recapture some of those old memories. But does that suit Trainspotting?

Admittedly, I could be entirely wrong about T2: Trainspotting. The reviews are overall decent. Director Danny Boyle, now an Oscar winner, has been routinely exceptional and has grown as a filmmaker rather than reverting and falling prone to wallowing in pools of nostalgia … like some other Miramax-brother. Maybe Boyle can break the almost universal trend and possibly have something unique and clever to say about life and aging through these characters – criminals and former criminals alike. Or maybe not. Probably not. (The ‘Choose Life 2.0‘ speech in the trailer for T2: Trainspotting is a quite cringey example of the Obligatory Callback; taking something that was once unique and defining and giving us an ersatz copy whose sole purpose is to make us salivate over nostalgia like the Pavlov dogs we are.)

The decade-plus sequel is a really tough sell and even harder to pull off. For something harsh and gritty like Trainspotting, what else is there to say about these characters? Will this sequel be ‘necessary,’ or will it merely be ‘enjoyable enough’? Is ‘a fun time’ enough enough to warrant its existence, or maybe they should have left well enough alone? As great as Trainspotting was, some stories work best with one volume.

God help Blade Runner 2049.