Show of hands: Who really understands how and why the American economy crashed and burned back in 2008? Adam McKay’s manic and eager-to-please comedy nightmare The Big Short states from the start that this is a confusing subject and instantly zeros in that this confusion is, of course, intentional. Wall Street is well aware that few of us really know what “subprime home loans” and “collateralized debt obligation” actually mean. Those dryly boring monikers aren’t going to motivate much enthusiasm for outside research especially when the few in the know have little intention of actually attempting to comprehensively make these terms accessible (some billionaire somewhere might lose a few bucks in that event).

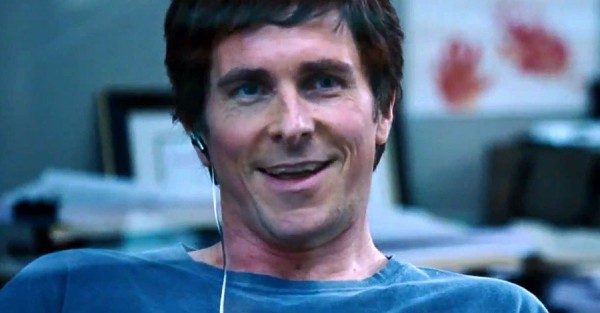

Admirably, McKay walks us through the process like a doting father hand-holding a toddler. Or perhaps more succinctly. a brotherly frat dude holding up the beer bong for a reticent pledge. In The Big Short, McKay attempts to make “sexy” what led us down the rabbit hole to financial doom, employing a zesty, energized verve to what’s essentially an overly complicated word problem- he’s giving us our medicine with a rum and coke chaser. Employing an all-star cast including Christian Bale, Steve Carell, Ryan Gosling and Brad Pitt and nearly every gimmick in the filmmaking rule book, McKay achieves something quite noble: explaining the impossibility of America’s fiscal crisis in an entertainingly accessible fashion while maintaining just enough sobriety to gather audiences into a virulently angry, hopefully impassioned rage.

A formidable and ambitious undertaking indeed. One that begins as eccentric money manager Dr. Michael Burry (Bale)- who sports a glass eye and a hint of Aspergers- starts to take notice that all may not be copacetic while investigating sketchy home loans. With careful research and an economic-inclined brain, Burry senses the early tinge of forthcoming gloom- about three years ahead of the rest of us. As such, Burry makes the bold (and seemingly insane) decision to take billions of dollars of his investors’ money and put it into credit default swaps, basically betting against the housing market and one of the hallmarks of the American economy. This decision finds the attention of squirrelly banker Jared Vennett (a spray-tanned Gosling) and eventually the hot-headed, emotionally unbalanced hedge funder Mark Baum (Carell) and opportunistic young investors Charles Geller (John Magaro) and Jamie Shipley (Finn Wittrock).

From nearly the start, The Big Short has a sort of tonal issue that’s difficult to qualify even while it’s entertaining as hell. Gosling serves as the narrator of the film, often breaking the fourth wall and addressing the audience directly (a device that recurs throughout) and while his dialogue is informative and often delectable, there’s seemingly a disconnect that McKay and credited co-screenwriter Charles Randolph (The Life of David Gale)- the film is based on the novel by Michael Lewis, the same guy who wrote the books that inspired Moneyball (2011) and The Blind Side (2009)- can’t entirely sort out: Are he and his band of “loser, outsider weirdos” heroes or merely part of the problem? All of the main characters of The Big Short are positioned as essentially “the smartest guys in the room,” the ones who saw something that no one else could even fathom, let alone being to look for despite a pungent odor. Yet, they are also the ones who bet against the American economy and made billions in the process while millions of others lost their homes, jobs and livelihood.

That lies the challenging conundrum- simultaneously fascinating and frustrating for a film that seems so on the side of the Occupy Wall Street sect but still attempts to make heroes out of the men nevertheless in the upper echelon of the one-percent. We chart as these characters investigate the looming crisis with raised eyebrows and bemused shock- Baum associates Danny Moses (Rafe Spall) and Porter Collins (Hamish Linklater) even gently warn a lower-income tenant that they are in danger of losing their home- as the infuriating realization of eventual cataclysmic doom comes into focus but there’s a constant reminder that The Big Short may be trying to halfheartedly turn these men into demagogues. The actors instill a sense of compassion and vigor but McKay’s manic aesthetic sometimes becomes a bit too cluttered inhibiting many scenes a chance to breathe. The underlying question is do the filmmakers believe these characters are noble?

McKay glosses over this tonal divide fairly effectively in the first two-thirds of the film as The Big Short admirably puts into layman’s terms how the banking industry actually flows and how fiscal corruption became the natural order – showboating with celebrity asides from the likes a champagne-fluted Margot Robbie in a bathtub and an endless barrage of montages and flashy cutting. It’s in the final act when a righteous, call-to-arms temper is put in motion when The Big Short feels its most out of touch. Baum, in particular, is a curious character- one who’s enraged and contemplative but even with reticence, succumbs to profit off the gloom and doom of countless others. His character tries to stand as the moral compass of McKay’s complicated opus- Baum is even given the most heartfelt backstory saddled with a brother who committed suicide sometime prior- but there seems to be too much overall empathy for these smarty-pants dudes in the end.

The downside of McKay’s noble intention lies in that the movie comes perhaps a few years past prime relevancy as well as the cinematic ghost that looms in its shadow- that would be scathingly excessive indictment The Wolf of Wall Street. Martin Scorsese’s abrasive masterstroke palpably and vividly understood a culture spurred on by greed and one percent excess that it can’t help but short The Big Short, which is more or less a civics lecture designed for the YouTube crowd. If tonal discord and comparisons may be The Big Short‘s follies, there’s still much to admire here and McKay’s ambition is worthy of more than a gander; it’s particularly notable that McKay is same filmmaker responsible for sillier-than-sin works that include two Anchorman movies and Step Brothers.

Verdict: 3 out of 5

More entertaining than it has any right to be, Adam McKay’s The Big Short accessibly and admirably attempts to explain and explore the how and why of the 2008 financial crisis. Utilizing nearly every gimmick in the book (sometimes to an excessive and distracting effect), McKay underlines his film with a sense of moral indignation that’s sometimes at odds with the motivations of its principle characters. Still, his is an easy film to admire and vitally important if for nothing else than as a primer on banker jargon but a difficult movie to truly get behind as we are meant to find heroes out of the very men who bet against the American economy and won.