Silence is a film that took Martin Scorsese 28 years to make – twenty-eight years of pre-production drama and lawsuits with one of them being against him for not getting the film done. Slightly to the film’s detriment, Silence wears its struggles on the surface. With a runtime of 2 hours and 41 minutes, every moment is felt, and though powerful, doesn’t quite pack the emotional and spiritual punch that it promises. Scorsese undoubtedly delivers in the areas that seem to matter most to the director, the themes and visuals. However, there are small disconnects elsewhere in the film in terms of structure, acting, and overall narrative content that will leave the audience feeling drained and somewhat distracted.

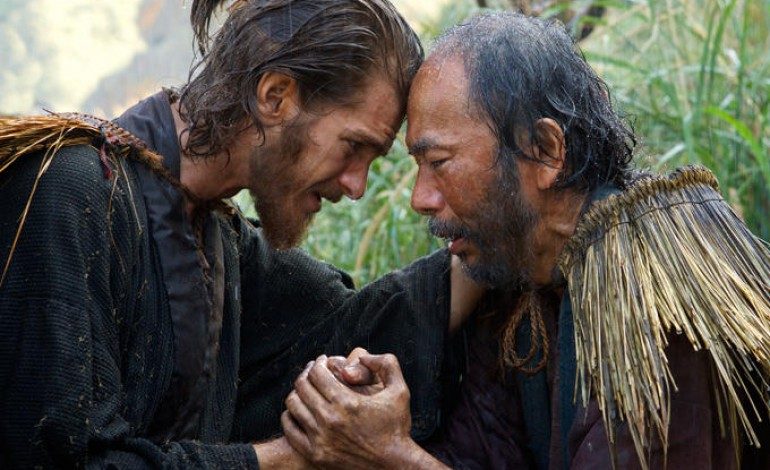

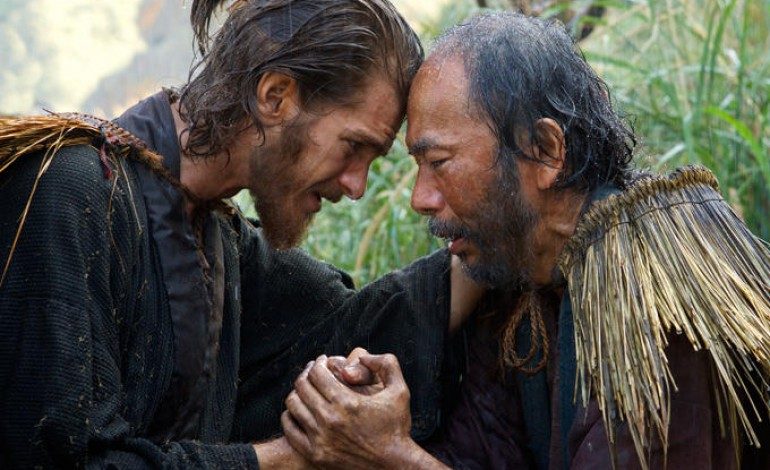

Silence takes place during the seventeenth century in Japan, a time when believers in Christianity and its missionaries – namely Jesuit priests – were being horrifically persecuted. After hearing that their mentor Father Ferreira (Liam Neeson), who has been living in Nagasaki for years without word, has supposedly apostatized (renounced God by stepping on a likeness of his image) at the feet of the Buddhist inquisitor Inoue, two Portuguese priests embark on an impossible mission to save him and their Catholic faith. Father Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield) and Father Garrpe (Adam Driver) smuggle themselves into Japan and encounter small populations of “Hidden Christians” practicing their faith in silence. Their army of two grows by secret, but once they are found out, their faith and religion is tested like never before.

Scorsese’s film is one clearly aware of its implications toward white European imperialism, a point that is made quite a few times by those wishing to do away with Christianity. The film does, however, propagate its own form of white imperialism, employing the conceit of the white savior coming to save a foreign country from its barbarism. Scorsese continuously uses the image of God – one particular visage of Christ in a crown of thorns that Rodrigues keeps remembering from his childhood – as a visual token of sacrifice and suffering. There is even one point in which Rodrigues (dehydrated and hallucinating) sees that same image when he looks at his reflection in the water. The picture transforms from Christ to Rodrigues and back again, further suggesting his role as a white savior. Scorsese does not make it so simple, though, where in the next moment Rodrigues maniacally laughs at the reflection. The film does acknowledge this later on as well, as Rodrigues is once criticized for comparing his suffering to Jesus, and he is never deemed to be unflawed or without sin himself.

Religious imagery becomes troublesome once again though, in a moment when Rodrigues worries that the Japanese Christians worship the icons he gives them (handmade crosses or the Virgin Mary imprinted in metal) more so than faith or the word of God. While a telling observation, it also exposes Rodrigues’ own fixation on iconography (his mental image of Christ) and Scorsese’s continuous saturation of iconic imagery throughout the film to stand in for an individual’s faith – particularly in the film’s final moments.

The rest of the film, however, unbeholden to Catholic icons, is a visual masterpiece. Scorsese shows restraint throughout, both from a near absence of score, and also through the quality of his visuals. The director, with the help of Oscar-nominated cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto (Brokeback Mountain), makes every camera shot count with pinpoint detail – from storming the foggy beaches of Japan’s islands, to more intimate moments of faithful solitude. Suffering is both represented in wide grandiose shots and within the recesses of the mind in close, personal, and emotionally captivating perspectives. Through these intimate moments, Scorsese capitalizes on his theme of “silence” and the power it has not only over faith, but also his visual story. The quality of images is at the same time subdued throughout and a reminiscent upgrade to his film The Last Temptation of Christ.

Unfortunately for the gorgeous visuals, and Scorsese’s mastery of vision, there is plenty to distract the audience and pull them out of the intensity of the film. Firstly, the movie’s linear narrative is told mostly through voiceovers, mainly through Andrew Garfield as Rodrigues in what is meant to represent letters he is sending back to Father Vallignano (Ciaran Hinds) in Portugal as well as prayers to God. Sometimes heard as welcome exposition, the film seems to rely too heavily on Rodrigues’ narration and misses an opportunity to show faith, suffering, and sacrifice rather than tell. Also, when the voiceover makes a transition from Rodrigues to Dieter Albrecht (Bela Baptiste), a German historian chronicling the end of Rodrigues’ journey, the quality of the voiceover turns from religious contemplation to corny narration.

The acting unfortunately does not do much in the way of carrying the film. Garfield does absolutely commendable work here, as does Adam Driver (who lost 51 pounds for the role), but both performances expose a disconnect between the actors and the material. I am reluctant to call it an immaturity, although it does seem that way in certain moments, especially with one using an ambiguous European accent and the other committing to the Portuguese, but both speaking in English at all times. Some fault is with Scorsese himself, though, who although was raised a Catholic and seems to know the religion well, seems also to tell a story not strongly rooted in Catholicism, but rather history and an emphasis on visual splendor. Little things like Garfield’s perpetually luscious disco Jesus hair, and the casting of Liam Neeson as a dissenting believer rumored to have taken a Japanese identity, – which will likely have audiences thinking back on his role of Ra’s al Ghul in Batman Begins – distract from the actors’ impacts.

Verdict: 3 out of 5

If you are someone ready to dive deep into a nearly three-hour film of religious suspense, you will come out feeling somewhat rewarded for the large slow burn. It is unclear how religious audiences will take to the film, as it lacks in dogmatic potency, though remains true to the Church’s ultimate teachings. Some will likely detest this film for Scorsese’s slight manipulation of white imperialism, but some will also praise it as a love letter to devout faith and perseverance. Whichever way the audience takes it, Scorsese inarguably delivers as a visual director, and tells a great story in the film’s silences.