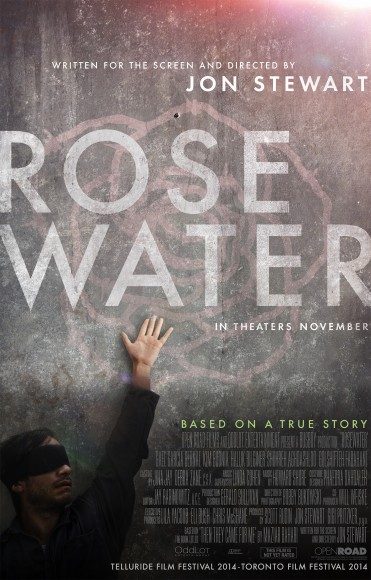

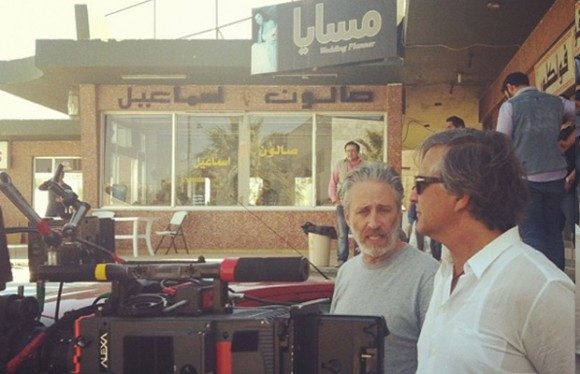

Rosewater is one of those odd films, like Boyhood earlier this year, where there’s almost as much to say about the making of the movie as the actual movie itself. Rosewater was written and directed by Jon Stewart – yes, that Jon Stewart, of The Daily Show fame. And to make it weirder, the story he’s telling here – the imprisonment of Iranian-Canadian journalist Maziar Bahari following the 2009 elections in Iran – is actually one his show was directly involved with. It even shows up in the movie, with Daily Show correspondent Jason Jones dramatizing the real interview he did with Bahari at the time, an interview later used against Bahari as proof he was an American spy. So Rosewater is a curiosity in that sense, but this is not a mere theatrical extension of The Daily Show. As the writer and director, Jon Stewart’s fingerprints are all over the movie, but it is its own entity, and moreover it measures up quite well.

Rosewater tells the kind of story you might expect Paul Greengrass or Kathryn Bigelow to take on – an immediately relevant, politically charged drama. Iranian expat Bahari returns home to cover the lead up to the elections for Newsweek, but ends up staying longer than expected, first to cover the aftermath (demonstrations both peaceful and less so, and widespread accusations that the election was rigged) and then against his will as a prisoner of the state. Along the way are discussions of the virtue of a free and open democracy, the overbearing influence of extreme religious regimes, and the importance of bravely bearing true witness.

It’s this last one which is most important to Rosewater. The movie strongly implies that truth is an unstoppable force, one which can be subsumed in the short term, but will erode a foundation of lies and abuse in the long term. The more people brave enough to bear witness, the more open the climate for discussion, the more rapidly the truth will find its way to the surface. As anyone who watches The Daily Show can attest, this is undoubtedly the motif of all Stewart’s work, and he’s found a way in Rosewater to express it through drama rather than satire. It’s a strong thematic and emotional core to the movie that does a lot to hold a few of the more tenuously constructed elements together.

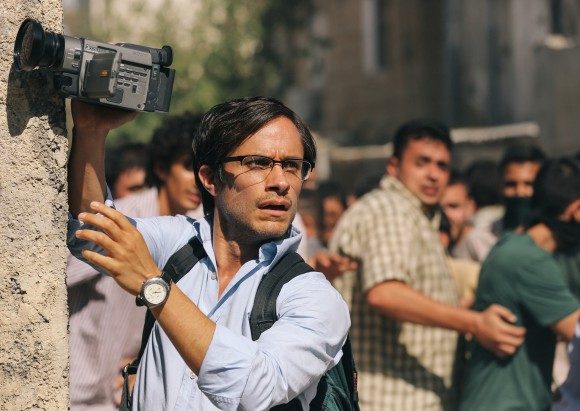

Just because this is a drama, however, don’t expect the whole movie to be straight-faced. Not only is this in the image of Stewart, who has an averred affinity for the comically absurd, but most good dramas are not without their comic relief. Those worried that Rosewater might veer too far in this direction, though, can put those fears to rest. The comic moments are well-grounded within the characters, specifically connected to Bahiri himself and his trying situation as a political detainee. Rosewater doesn’t sugar-coat the situation, either; comparisons to Paul Greengrass’s body of work are invited not only by the subject matter, but through the frequent use of hand-cam and newsreel footage, especially in the more frantic moments. I appreciated that Stewart went for a smoother look overall, rather than Greegrass’s notoriously bouncy cinematography, but Bahiri walks the streets of Iran with a camcorder, and Stewart isn’t afraid to pull from that feed to emphasize the reality of what’s being shown.

The casting of Bahiri is the other part of this movie which might, from the outside, seem a little funny. Mexican national Gael Garcia Bernal is a fine actor, but it’s easy to see where making him Iranian might strike some as odd. But like most of the concerns about Stewart in the director’s chair, worries about how Bernal would fit into the role can be put to rest. Bernal is more than up to the task of adopting a foreign accent, and while large portions of the movie require nothing particularly exceptional from him, he’s given several chances to shine as well and seizes them.

Bahiri was kept in solitary confinement after his arrest, almost his only interaction coming with the “specialist” assigned to interrogate him. Stewart uses these times in solitary to dig into Bahiri’s past, staging conversations between Bahiri and his deceased father, who was jailed in the ‘50s for being a communist, and his also-passed sister, jailed as a revolutionary when Bahiri was still a young boy. These interactions, along with the knowledge that Bahiri has a wife and unborn child waiting for him at home, do a lot to humanize him beyond the “unjustly jailed journalist” stereotype, and Bernal brings it home with a performance that emphasizes first Bahiri’s incredulity that anyone would think him a spy, then growing brokenness as the days and months in confinement drag on.

There to match Bernal as his nameless interrogator, identified only by his rosewater scent from which the movie draws its name, is Kim Bodnia. Bodnia renders Rosewater (as I’ll call him just to make it easy) a shockingly sympathetic figure, one who certainly harbors cruelty and anger, but also feels emotionally threadbare from his work accosting prisoners. The validity of his character in real life may be up for some debate, but in the context of the film, Rosewater makes meaningful contributions to the idea that forceful repression is something that cannot stand over time, that cruelty and bigotry will eventually self-identify and crumble.

The movie is not without some flaws; the plot is perhaps not quite as cohesive as it wishes, and while the movie does a decent job of getting to know its main character, there’s a something lacking in how it connects him to the moving tides of world events. Some of that insularity comes from attempting to have the audience share in Bahiri’s isolation, but the audience is always observing more than experiencing Bahiri’s confinement, so the moments where the movie breaks wider to show Bahiri’s position as a catalyst in world events feels a bit tacked on. It should also be noted that while Stewart is plenty capable as a director, it does feel like he’s still experimenting a little with the bag of tricks at his disposal. Rosewater is a compelling drama, but it is perhaps guilty of having the eye of a documentarian more often than is useful.

The Verdict: 4 out of 5

The moments of Rosewater that lands are very strong, and the thematic conviction on display does a lot to cover up some of the flaws that do exist. Audiences should also be reassured that those flaws aren’t a result of surface level oddities like Gael Garcia Bernal’s casting as an Iranian expat, or The Daily Show’s Jon Stewart being the man behind this movie. In fact, one of the strongest endorsements for the movie I can give is that this feels thoroughly like a Jon Stewart movie, proving an adroit blend of his social consciousness and observational humor within the context of a drama. Rosewater may struggle at times to say exactly where the impact of its story should land, but there’s no denying that it has impact, both as a piece of entertainment and as a bell for social change.