Put simply, if witnessing brutality in an aesthetically pleasing way sounds like a good time, Andrew Neel’s Goat (produced and featuring an odd appearance by James Franco) is the film for you. Surrounding the fictional events of a fraternity hazing gone awry, Goat pushes the limits of viewing pleasure by indulging in Neel and Franco’s apparent fascination with careless violence and the performance of masculinity. The silver lining: Neel’s directing and visual design takes the film in innovative directions, while his star, Ben Schnetzer (Pride, Warcraft), carries the film by way of a particularly memorable breakout performance.

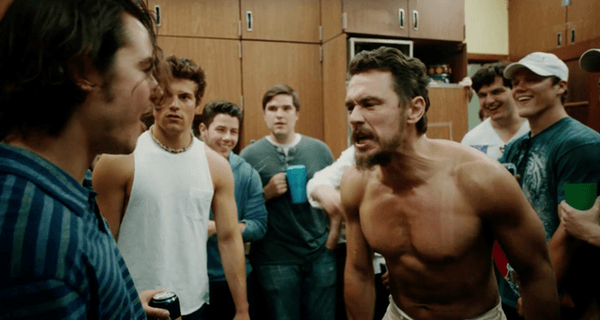

Goat is based on the true story of Brad Land and his titular memoir which sees the author as a 19-year-old college student recovering from a personal tragedy – in the form of a random jumping that leaves him beaten senseless – when he decides to pledge his older brother Brett’s (Nick Jonas) fraternity. “Hell week” lives up to its name as the fraternity brothers unleash new and sickeningly creative forms of brutality while hazing Brad and his fellow pledges under the euphemistic disguise of “initiation” rituals. Brad is tested on every level of physical, emotional, and psychological strength and learns the true meaning of brotherhood in the hardest way possible.

This is not Franco’s first time being involved with the subject of senseless brutality among young adults within the modern American landscape. He also broached the subject in Palo Alto, a film based on Franco’s memoir of short stories which he also adapted for the screen. In that film as well as in Goat, violence is connected to an underdeveloped and Neanderthal-like stage of growth among American youth where masculinity is exploited and twisted in its performance. Goat goes even further to explore the consequences of masculinity when embedded in a social institution like a fraternity and under the weighty symbol of “brotherhood”. His subject matter is undoubtedly intriguing; however, he relies too heavily on overpowering images of cruelty to tell the emotional story in an effective way. His ruminations on brotherhood are shallow and Neel leaves it to his actors and the audience to reconcile the plot with its deeper meaning.

With a potentially deep well of emotional situations to pull from, Neel’s actors are left responsible to get those messages across, and for the most part, they deliver. Up-and-coming actor Ben Schnetzer is given the bulk of emotional and psychological burden to convey and pulls it off magnificently while left largely to his own devices. Recovering both physically and mentally from an act of cruel and unprovoked violence, Brad experiences literal wounds as well as a bruised ego and shame for his inability to fight back. This brings a mixed bag of feelings to the surface, or rather just under the surface, as Brad silently deals with the implications of losing a fight while living under the influence of a traditionally masculine older brother and the fraternity culture, one of the loudest and stereotypical symbols of masculinity. Schnetzer maturely brings Brad’s tortured persona to the screen, accurately portraying the warring feelings of shame, personal guilt, youthful ignorance, and the need for acceptance buried under the mask of false strength and confidence.

Singer Nick Jonas is also given a hefty task in playing Brett Land, Brad’s shining example of true masculinity and all the desirable traits that it accompanies – bravery, self-control, power, and “cool”. Brett is not only these characteristics, though. He is also a caring and thoughtful older brother who is torn between the name and the reality of brotherhood. Very likely Jonas’ most challenging role to date, his effort in baring these emotions is apparent and noteworthy; however, the desired effect is not nearly as strong as with Schnetzer. Neel’s supporting cast, particularly rising indie actor Danny Flaherty (King Jack) and Gus Halper in one of his first feature roles, do well to pick up the slack and add different dimensions to the study on male virility.

Although Land’s memoir likely weaves a similar tale of cruelty, Neel’s interpretation ignores countless opportunities to explore Brad’s mental and emotional obstacles, opting rather to exploit brutality for the sake of art. Neel presents audiences with domineering images and scenes of physical savagery. He does so with camerawork indicative of a horror film, with one scene in particular even seeming to pay homage to The Human Centipede. The look also resembles reality television at times in camera shots set up to feel organic and unplanned. The almost complete lack of a soundtrack or score adds to the terror, making the violence more real, and the performances even more demanding to counteract the brutally intense blow to the senses. Ambient sounds often work directly against the actors as they are forced to fill deafening silences with their own emotional interpretation of the material.

The most impressive aspect of Neel’s shots is his unique lighting design. Working in unison with the silences are scenes lit by a single spotlight, creating a stark atmosphere of isolation. Brad’s first and most prominent experience with violence as well as every subsequent incidence within the fraternity, and even sexual encounters representing the performance of violent emotion, are all in danger of being enveloped with darkness – if not for a single bright light. The lighting illuminates the isolation caused by contaminated masculinity and also the general perils of emotional development. Neel, in this small way, is able to find the individual within his cold and mob-view of violent humanity. The lighting and silence alone, however, are not quite enough to provide a satisfying thematic and emotional depth.

Verdict: 2 out of 5

I was very close to giving Goat a better score if only for several of its memorable performances and creative artistic qualities. The fact that Neel seems to revel so deeply in brutality, however, and ignores opportunities to delve deeper the individual and human relationships, creates a prominent imbalance in the film. The last twenty minutes of Goat attempts to add clarity and resolve through a heart wrenching incident and the emotional reunification of Brad and Brett (featuring a visually stunning final shot), but its effect pales in comparison to the over-stimulating violence preceding it.