Welcome to Revisionist history, where we, unencumbered by the demands of studios and profit margins, try to imagine different and better versions of the movies that are out there. This is not a review; it is a full-spoiler discussion of what works and what doesn’t, particularly from a story/concept standpoint (i.e. unless there’s a particular tic that is distracting, it’s hard to account for a poor acting performance or other failure in execution alone other than to say, “Do better.” Which isn’t very interesting or helpful to anyone.)

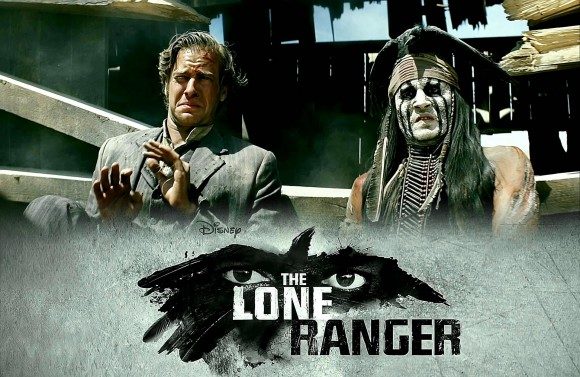

This week, we’re revising The Lone Ranger.

Oh boy, do we have some work to do.

As you may have noticed, reviews for what otherwise might be titled Pirates of the Wild West have been pretty universally negative. And while the movie is certainly not good, I’ll deign here to say that, insofar as they are considered unto themselves (without regard for the larger story they’re a part of), only two pieces were truly bad: the score, and Johnny Depp. The rest could do no more than elicit utter apathy. Again, doesn’t mean that most of the film got it right, only that it’s not altogether the unwatchable train wreck (pardon the pun) some are making it out to be.

And with that, let’s move into full revision mode, because bad decisions that elicit no emotional response are only very marginally better than bad decisions that elicit negative ones.

Let’s start with the tone of the movie. Very clearly it’s going for the same sort of mix of physical comedy and compelling action that made the original Pirates film such a rousing success. I wasn’t just talking about the men behind the movie when I said this was Pirates of the Wild West. The Curse of the Black Pearl pulled this off very effectively by giving us characters we cared about and understood as characters before throwing them into the action. Think about our introductions to Will and Jack. Jack is seen sailing into the harbor on a sinking ship. It’s grandiose and silly and fun to watch – but it’s also effective. He makes it to the harbor. The rest of the movie, his character follows this exact pattern. We want to watch him because he’s a funny character that engages in amusing physical comedy, but we’re also very aware that he’s deadly capable. Likewise, we meet Will when he’s delivering a sword to the governor. He’s not the goofy character that Jack is, but we still see him break a chandelier or some such thing on a wall and, embarrassed, try to cover it up. Physical comedy that informs his character as an overeager, energetic young man. When he actually gives the governor the sword, he demonstrates a fancy bit of swordplay, and we see that he’s also very capable. Again, a mixture of amusing goofiness and deadly seriousness that’s wrapped up in the characters. It lets the audience know exactly what to expect (tonally and from their characters) from the very start of the movie.

So what about The Lone Ranger? We’ll get to the ridiculous frame in a moment, but let’s start with the first time we actually see the Lone Ranger and Tonto on screen together. They’re holding up a bank. And sure it’s the desert west, not the lush Caribbean, but everything is drab, all browns and tans and blacks. Tonto and the Ranger have guns and are serious. Sure, there’s a nice little homage to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid when the Lone Ranger has difficulty declaring that it’s a bank robbery, but let’s not forget that Butch and Sundance are antiheros. This hard-boiled, desperado nature, then, is our expectation for the characters, and since they are the main characters, our expectation for the movie. And really, most of the movie sticks to that. The problem is that this creates a gritty world. “Gritty” may be the favorite buzzword of Hollywood these days, but for The Lone Ranger it’s a miscalculation on multiple fronts. First off, the audience is never as willing to buy Tonto’s eccentricities as they were Captain Jack Sparrow’s because they don’t seem to fit in this world. Pirates was always a place of magic and wonder. The wild west is a place of grim survival. To which the answer may be said, “but Tonto seems to have actual magical powers.” True, but look at the way he goes about it, the kind of magic it is. It’s most akin to necromancy. If he’s actually doing magic rather than just being weird, the magic is no longer goofy fun, but another bit of the seriousness. By the time we get to the first plot point, the ambush and murder of six (or seven, depending on how you want to count it) lawmen, this movie’s not going anywhere that could be considered fun physical comedy.

Part of this insistence on the part of the filmmakers seems to be a determination to move away from the campiness of the Lone Ranger as a character and intellectual property. Throughout the film, if they can’t make it serious, they make the campy elements jokes, so the audience knows they’re not taking those moments seriously. Though at the end of the movie, the moment when Tonto admonishes the Lone Ranger never to say, “Hi, ho Silver, away!” again is perfectly emblematic of the entire movie. It’s impossible to make a realistic western where the main character uses guns but not lethal force without leaning into the camp a little bit.

So back, for a moment, to the frame. This just about broke the movie for me (you know, besides the other ways it was broken), but it took me a while to figure out why. On the most basic level, it impedes the audience’s ability to suspend disbelief. If we’re going to embrace the inherent camp of the Lone Ranger, it has to be as simple as possible for the audience to lose themselves in the movie. Otherwise the camp isn’t fun – it’s just campy. That’s very important. But the frame of the little boy talking to the elder doesn’t work for another reason beyond the boy’s Princess Bride-esque – though far more annoying – interjections.

We’re beginning to set up an alternate movie that isn’t afraid to be unapologetically a little unrealistic. Not weird, just pushing disbelief. Done right, a framing mechanism could actually aid this, letting the audience know that some abnormal stuff might happen without destroying the fun of the events themselves. The problem with the existing frame is that it clashes with the story we’re told. The grittiness of the movie suggests that what we’re watching is fairly objective history. The framing mechanism is geared more to subjectivity. The frame, and the boy calling out errors, suggest that this is all a tall tale in which the audience is a participant teller, like a child being told a bedtime story. But Tonto’s story is presented as fact. The movie doesn’t even manage to ask an interesting question about the nature of what we accept as valid.

Ok, so we’ve got tonal and structural stuff fairly well established. Now let’s look at the narrative itself.

The Lone Ranger chose to tell an origins story. While my father is fairly well versed in The Lone Ranger, I am not. Like me, I’m guessing the majority of the people who thought about seeing this movie knew about three things about the property: 1) The main character is a crimefighting Texas Ranger who wears a mask, 2) he has a native American sidekick named Tonto, and 3) he rides a white horse named Silver. So you might think an origins story is the right place to start.

If you’re reading this article, I’m assuming you’ve seen the movie already. Think about this: did you need to know anything more about the character than the three things above? It’s a failing of the movie that there is little character arc for any of the characters, but beyond that, did you ever care that the Lone Ranger was motivated by vengeance for his brother’s death? And if you did, is there any reason he should keep suiting up as the Lone Ranger and putting himself in harm’s way now that that vengeance has been accomplished? My answer to both questions is no. I didn’t care why the Lone Ranger decided to be the Lone Ranger. There’s enough intrigue in his relationship with Tonto and his peculiar methods of crimefighting. I’ve argued before (and I think more than once) that there should have been more of Superman’s origins story in Man of Steel, and lest I be called a hypocrite, I’ll take a moment to defend my view here.

And with all that in mind, let’s start laying out our revision.

We open on an in progress stage coach robbery. The Lone Ranger and Tonto foil the robbery, but without the use of deadly force. In fact, they even stop the man riding shotgun on the coach from killing one of the outlaws during the fight. It’s pretty incredible watching them shoot the guns out of the outlaws’ hands and other nonlethal tricks. They drive the outlaws off and learn that the coach is carrying payroll for the railroad construction and offer to escort it into town.

In town the Lone Ranger and Tonto speak to the railroad company man and he thanks them. The sharper among us may notice that he addresses himself to the Lone Ranger only, never to Tonto. Tonto makes a comment about the railroad angling through Indian land, and how that would violate the treaties they’ve set, but the railroad man says they’re going around. He tries to hire the Lone Ranger and Tonto to investigate a series of robberies well up the track. It seems supply chains are being hit, and money and supplies are regularly not making it to the front of the tracks, not to mention food, medicine, and other supplies that settlers are counting on. They decline the employment, but say they’re headed up that way anyways and will look into it. It seems there’s word of a crooked lawman up that direction, and they intend to look into it.

Much of the town turns out to see them off, and maybe there’s a particular young woman whose pretty smile catches the Lone Ranger’s eye. But before there’s any time to linger, it’s, “Hi, ho, Silver, away!” and they’re off. They ride and make camp and ride some more, talking as they go. After several days, they come across a homestead on fire and rush in to help the family rescue their livestock, belongings, and young child. The fire was set by cronies of the sheriff the town several miles up for failing to pay new “taxes” – basically the cronies’ whiskey fund. They ride on to the town, a place once gleaming, now in disrepair, with makeshift saloons at every corner. They confront the sheriff, who mocks sympathy and apology and then throws them in prison.

That night they manage to escape, but are run out of town by the chasing guards before they can retrieve horses or effects. They make for water to refresh themselves, regroup, and come up with a plan. They stumble onto a camp of supposed outlaws, but quickly learn that this is actually the deposed sheriff of the town and his deputies. It seems they’re not the only displaces lawmen, and while most towns have made it though better off, all along the track sheriffs and marshals have been bought off or replaced – by the railroad! His posse and others like it have been the ones robbing the trains to try to disrupt the railroad’s business. Tonto and the Lone Ranger admire their pluck, but admonish them that their actions are hurting the townspeople, too. There has to be a better way to stop the railroad from disrupting justice. And more immediately, they need to get the town out of the tyranny of the new, false sheriff. They start thinking up a plan.

We jump cut to the plan in action. It’s quirky, but effective, and in no way superhuman. They depose the false sheriff and his cronies, and they find written instructions signed by…none other than the railway man they met earlier! And he’s planning on going right through Indian territory! He’s got to be stopped! The Sheriff and his deputies will stay oversee the town and help reinstate the other sheriffs on the line, but for the Lone Ranger and Tonto, it’s Hi, ho, Silver, away! Except that what’s faster than a horse? An iron horse.

Back at the town on the (current) end of the line, the train in the distance is eagerly anticipated by the railroad man. But when the boxcar opens up, out thunder the Lone Ranger and Tonto. They arrest the railroad man but it’s too late. The man is thrown in jail, the railroad stopped, and they’ve saved the day.

Now, that’s a pretty bare-bones outline, and probably needs some beefing up in the middle plus a big action bit at the end, but the idea is there. We buy the Lone Ranger’s nobility and unusual methods because they’re consistent, effective, and make his heroism all the more impressive. He’s an everyman, but an everyman living an extraordinary life. We like seeing how he’s able to accomplish his heroics because they’re difficult. We lean into the campiness of the Lone Ranger as a character and get to go for one heck of a fun ride in return.

And that’s our revision. Have your own? Let’s talk about it in the comments!