Welcome to Revisionist History, where we, unencumbered by the demands of studios and profit margins, try to imagine different and better versions of the movies that are out there. This is not a review; it is a full-spoiler discussion of what works and what doesn’t, particularly from a story/concept standpoint (i.e. unless there’s a particular tic that is distracting, it’s hard to account for a poor acting performance or other failure in execution alone other than to say, “Do better.” Which isn’t very interesting or helpful to anyone.)

This week, we’re revising Lee Daniels’ The Butler.

Let’s talk about The Butler (excuse me, Lee Daniels’ The Butler). I was rather excited about this movie. In fact, I actually had the chance to read the script a few months ago, and it immediately reminded me of Forrest Gump, one of my all-time favorite movies, albeit a far less comic attempt. Like Forrest Gump, The Butler is an attempt to humanize the broad swath of American history though a very personal story. It’s also going to provide a point of reference as we attempt to tackle our revision of The Butler, as after seeing the latter, Gump has proved to be a far superior film.

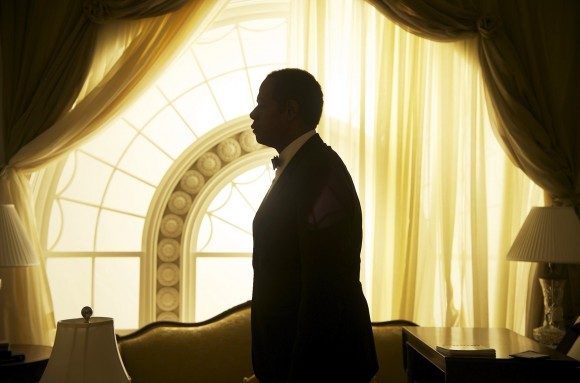

Why is that? Well, let’s start with the setup. In both movies we begin by coming in on a man sitting and waiting. But in Forrest Gump, we immediately meet our protagonist. We get to know him a little through his interaction with others. We get an introduction that explains not only who is narrating the story, but why. In The Butler, we see the elderly Cecil briefly, then immediately cut to his childhood self. The connection between the older and the younger isn’t lost, but we don’t have any indication as to why he might be narrating this story for us, or from where.

This is where the chief failing of The Butler begins. In Forrest Gump, you always feel as though you’re sitting on that bench right next to Forrest. It’s a personal story that you feel in close contact with. You experience the emotions of the decades over again through the particular stories of Forrest and Jenny. I never felt that with Cecil, or with Louis, either (though it’s a love story of a different sort, Louis is undeniably Cecil’s Jenny), and I don’t think it can be written off to a lack of racial identification. Yes, I’m a white guy writing about black people in eras I never personally experienced, but if the movie’s doing what it’s setting out to, shouldn’t that not matter?

Understanding of a character comes down to understanding motivation. Why does a character do what he or she does? On a surface level, this is never a difficult question in The Butler. Beginning with the scene in the cotton field where Cecil’s father is shot, we supposedly know why he advocates passivity. But this doesn’t hold up under close inspection. About a scene later we see Cecil taking drastic action – breaking into a bakery. And in what is an all-around exceedingly odd scene, he sits there at the scene of the crime, and when he’s discovered neither Cecil nor the ship’s proprietor reacts as you’d expect one to when discovering a burglar. What are we supposed to do with this information? It would be one thing if Cecil experienced another negative result from this experience, but he is, in essence, rewarded for his daring. This becomes the pivotal moment, far more so than the death of his father. Learning to serve at that hotel is the formative experience for the rest of his career, and it resulted from a moment of brash action, not reservation.

So as we transition into the adult phase of Cecil’s story, the part that gets beyond mere setup into where the action is really supposed to take place, we don’t really have a good idea of who Cecil is as a person. We see his mask that he puts on for the white folks, but he comes off kind of bland personally, and we don’t know what motivates him to, say, go ask for raises for the black staff from the Chief Usher. We don’t see, for example, a white staff member promoted above him. Not that we need to. This is, after all, the story of Cecil and Louis. They should always be our focus.

And in that sense, some of the supporting cast can actually be distracting. Characters like Oprah Winfrey’s Gloria Gaines or Cuba Gooding, Jr.’s butler Carter are well drawn and complex, but they also steal screen time that could have been used to develop Cecil or Louis further. For example, there’s an entire subplot with Gloria’s struggles with alcohol and infidelity. It’s a great touch, but it makes the film feel busy. And again, it keeps us at a distance. Instead of (metaphorically) zooming in on just two characters, we have to keep a wide angle to see all these other people and their arcs.

For our revision, we’ll open not on a man in the White House, but on a cotton field, and we’ll have no narration. We see a boy – sweaty, sore, tired, but happy because his father is next to him. When a female worker, we won’t even make her Cecil’s mother, is taken to be abused by the overseer, his father tries to stop the white man and is shot for his trouble. Cecil soon runs away. He comes into a town and is seen by an old server loitering outside the hotel, eyeing pastries through the window. That night, Cecil’s back outside, about to break in when he’s stopped by the server, who takes the boy in and trains him as a worker. Cecil grows up under this second father’s tutelage, learning how to survive, even thrive, in a white man’s world, as we see him stoically, patiently serving during the day and having fun when off duty.

Jump forward a number of years and Cecil’s serving in a swanky D.C. hotel. Maybe we see him drive home from work and see that not only does he have a car, but he definitely lives in the nice part of the black neighborhood. A modest house, sure, but his wife and two sons aren’t starving. Cecil gets the call to come interview for the White House job, but we’ll add a little twist – he’ll have to take a pay cut to go work there, but Cecil understands the honor of the position and takes it anyways. And maybe this is a minor point of contention for Louis. Maybe Cecil goes back on a promise to help pay for college because he can’t afford it with this new job. Before this conversation, we’ll have already had the scene where Cecil first serves President Eisenhower, so he goes back to the fact that he served the president as defense to Louis.

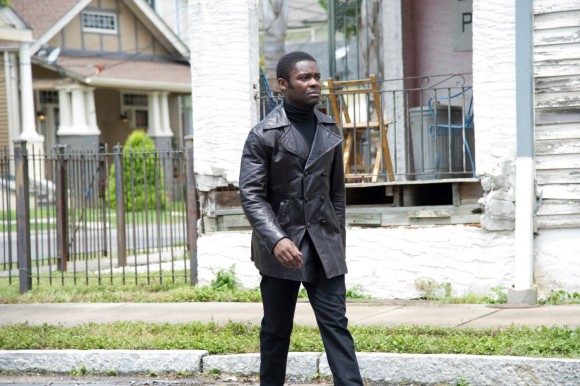

So as we proceed, Cecil’s working long, thankless hours, and rather than see Louis just jump into being a radical, we see him experience the difference between the equality of people within his all-black college and the segregation of the outside world, especially in the south. Maybe Gloria even becomes the proxy for their relationship for a while, if you want to keep her subplot. Louis calls home looking for fatherly advice, but Cecil’s never there, always working. It seems the happy Cecil, the one we might have formerly seen bringing down the house when he’s not go his server’s mask on, is present less and less. This might even become an important runner through the film – is Cecil personally capable of letting go as he spends more time occupying the facade of the black butler character? Meanwhile at college, Louis sees how he can sometimes be free of the duality he grew up around (face for white people vs. face for black people) and he begins to take interest in the civil rights movement, spurred on not by some girl (the persistent girlfriend character is too much a scapegoat), but by a desire to change things. And from here we begin the march through history.

But it’s at this point that we also need to be especially careful in our revision. Remember, this has to be a personal story, not just a historical panorama. Returning to Forrest Gump as an example, we need particular events like Forrest’s Vietnam heroics or Jenny’s near suicide. This is easy enough to accomplish with Louis. He’s present at sit ins and the like. The only change that really needs to be made is to focus on him particularly rather than the group, and choose a few specific moments instead of painting him a character in every significant event. We need to see that he’s caught between the supposed safety of the life his father provided and this new path he’s chosen. He probably even needs to chicken out a time or two. This would probably make his eventual turn to the Black Panthers more real to us as well, and let’s say that instead of backing out before they go through with an attack (like he would have early in the film), Louis goes through with it only to see the murder for the horror it is. We get a nice character arc for Louis that grows him into an activist adult.

Cecil is a bit harder, but I think like Louis it comes down to choosing between comfort and action. Let’s still place Cecil adjacent to some of the history of race relations, but instead of the presidents being the white people we focus on in the White House, let’s make it some white staff members. Cecil loves his job. He loves the dignity of it, as he sees it. But that’s going to get eroded over time as he sees both himself and others struggle to advance. Louis will probably be used against Cecil, and Cecil needs to be caught between pride when he sees those like his son affecting opinion in the seat of government and horror at his son being both beaten and arrested. His fatherly instinct, not to mention his personal persuasion, will be to maintain safety, and this is what he’s got to fight to overcome. While Louis is fighting for legal equality, Cecil is doing the same for de facto social equality. His arc is about not being afraid to stand by a controversial opinion in mixed-race company, demanding the respect of his peers because he, in fact, is earning it every day.

Like the existing film, Louis’s actions will be juxtaposed with Cecil’s, but with any luck they’ll both appear both more active and more real to us. They will move to a similar end from roughly opposite directions. The triumph of our story isn’t the historical movement of race relations – though that is a certainly a victory to be highlighted – but the triumph of love between a father and a son, and that by their actions they are able to stand together of one mind having overcome the struggles along the way.

That’s our revision of Lee Daniels’ The Butler. Have your own? Let us know what you’d do differently in the comments.