Wow, that was unexpected. In case you missed it, it was announced that James Cameron would be making not only two Avatar sequels, but three. That’s right, four Avatar movies total, and the final three filmed back-to-back-to-back. And while it’s hard to imagine that these films will lose money (in fact, I’d be willing to bet that the first one comes close to grossing enough to cover production costs of all three), I’m not sure this is a trend Hollywood’s smart to continue.

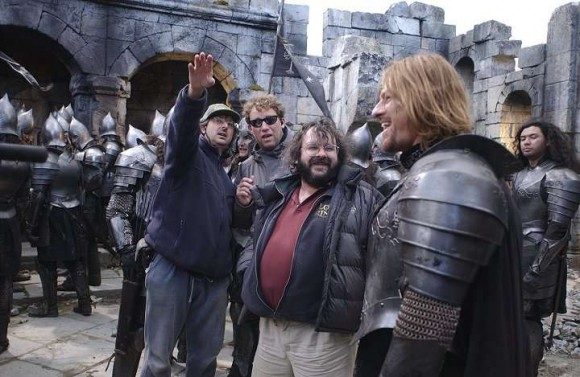

There’s a notable history of shooting films back to back – Superman and Superman II, Back to the Future Part 2 and Part 3, and Trial of the Pink Panther and Curse of the Pink Panther all did it, for example. But it’s a trend that seems to have taken off in recent years, beginning with New Line’s gutsy decision to give Peter Jackson more or less all their money to go make The Lord of the Rings back to back to back. It’s hard to remember now, but that was considered by many a foolishly risky move at the time. J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic fantasy tale was considered by many to be unadaptable, unfit for the big screen. And while shooting back to back is generally reserved for sequels (as is the case for the aforementioned Avatar films), it seems to me that the breakout success of The Lord of the Rings has made studios more willing to fork over huge chunks of money for multiple films.

Let’s look at a list of major movies which have come out and/or have been in production over the last 10+ years that were filmed back to back:

- The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions

- Kill Bill Volume 1 and Volume 2

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest and At World’s End

- Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima

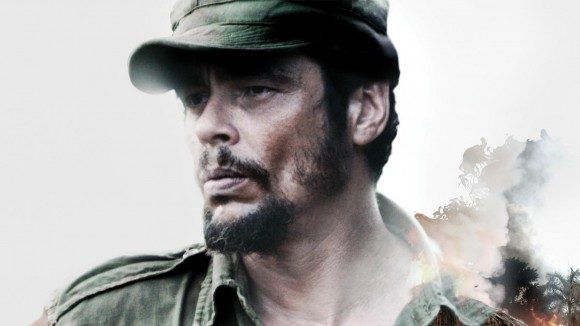

- Che Part 1: The Argentine and Che Part 2: The Guerilla

- Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1 and Part 2

- Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn Part 1 and Part 2

- The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, The Desolation of Smaug, and There and Back Again

You look at that list, and there’s only a couple that jump out as very risky. Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima were hardly a sure thing. Letters starred Ken Wantanabe, but his box office draw is limited, at best, and Flags had no major name stars. That said, World War II movies are historically popular, and the films were backed by director Clint Eastwood and producer Steven Spielberg. Kill Bill was shot as a single film, and only made into two later. The Hobbit was probably a little risky, particularly given Peter Jackson’s decision to shoot in 48 frames per second, but peripherals like leaving the New Zealand sets intact as tourist attractions mitigate most of the risk there (which couldn’t have been that high to begin with). The only films on the list that lost money were Che Part 1 and 2. Steven Soderbergh directed and Benicio del Toro starred, and while those are names that may be compelling to someone who knows movies, they’re not major draws for the general public. And even though the films barely made any money, at a $70 million budget for two films, that’s not a world-ending loss for the semi-major companies involved like Wild Bunch and IFC Films.

So why am I getting worked up about three Avatar sequels? Well, because whether this is the thing that leads to the massive collapse and paradigm shift in the industry that George Lucas and Steven Spielberg predicted a little while ago or not, I don’t think it’s good for movies, and I don’t think it’s good for the consumer.

Ok, time for a little philosophical background. Let’s take as a given that creativity is a good thing in the movies (if you disagree, please let’s talk about it in the comments). We want innovation, new twists on old tales, new ways of telling stories, new stories to be told. Creativity is what gives life to the movies. Therefore, a goal should be encouraging creativity. There are a couple things that pretty consistently spur creativity in really positive ways, whether you’re talking about movies or not. The first of these is a freedom to fail. To be creative, you have to take risks, to try new things and new combinations of old things. The need to succeed and other stressors can actually inhibit the brain from making new and useful connections. Writers will tell you how they threw away half a novel, but had to write those pages in order to arrive at their final product. Even physical sciences, which we usually conceive of as having definitive right and wrong answers, are dependent on freedom of failure. Experiments do not always go as planned, but there’s always something to be gained, even if it’s as simple as, “Don’t do that again.”

Paradoxically, the second thing that spurs creativity can often be limitations. Limitations eliminate the obvious solution to a problem and force innovation. Maybe the best (and most doggedly harped upon) example in the movies is the Star Wars pictures. As many have said, part of the reason the original films are so much better than the prequels may well be George Lucas and his coworkers were severely limited by budget, technology, and outside influence (the last of these being a “limit” on George Lucas more than the production as a whole – two brains are better than one isn’t just an aphorism). Can you honestly imagine Yoda being created as a puppet in today’s world?, I mean, he was in The Phantom Menace, but all he did in that movie was sit in a chair and then walk about two yards, and for the next film he was replace. The entire Dagobah set had to be built several feet off the ground with ridges cut out along pre-blocked lines so the puppet could move through the environment. At it looked great. It was a tangible world and character that the CGI Yoda endlessly flipping around the screen didn’t come close to matching.

So back to Avatar. James Cameron now has however many hundreds of millions of dollars committed to him, and he’s got to deliver on three films. Now in one sense, that might be considered a good thing. “He’s already got the money committed,” you might say. “Goodbye, stress.” Maybe, but James Cameron isn’t worried about putting food on the table (if you want to see more on the science of motivation, by the way, check out this excellent summary). I think Cameron’s internal monologue goes a little more like this: “I’ve got one chance to get this right, one chance to shape what people will think of me and my work for the next decade. If I screw one film up, I don’t get to reflect, change my approach, and fix it on the next one. If I screw one film up, I probably do it to all of them.” In short, there are heightened expectations when you move from one picture to three. Now, let’s be fair. Everyone has expectations placed on them, no matter the job. Whether someone is able to rise to those expectations or whether they’re crushed by them says a lot about a person. But when you make multiple films in a row, the expectations are appropriately higher. That’s stressful, and it can lead to trying to make sure you don’t screw up instead of risking failure in the pursuit of something special. Not only that, but it’s suddenly a lot easier to choose the easy way out of a problem, or if not necessarily the easy way, at least a singular way. Maybe there’s a similar issue to deal with in each film. If all three are being made at the same time, the same solution gets applied across the board. Make them separately, and maybe new ideas get brought to the table each time.

Look, maybe this is a cynical viewpoint, but making one movie is risky enough, probably why the majority of these investments have come on sequels to established, hit franchises. But it does seem like this is becoming a more common occurrence, and that’s something to watch out for. I’m also not ignorant of the economical reality of may of these big-budget movies: they’re so expensive, they need to appeal to the widest possible audience in order to make money. When these things are being made, innovation isn’t necessarily the studio’s end goal as we’ve postulated above. All I’m saying is that if we want movies to thrive and evolve and keep us on the edges of our seats, maybe doing this multi-picture business isn’t the best idea, even for the big ones. Good movies aren’t made on an assembly line. We shouldn’t treat them like they are.