When a piece of media makes it big – I’m talking massive followings with fans creating online spaces to discuss theories, begging the author to answer questions on their favorite characters, wondering about potential adaptations hits kind of big – one of the greatest things a production company can gift a fanbase is the promise of more content. While anticipation can run high, apprehension can run even higher for producers to do justice to a favorite character or prevent botching of a beloved storyline. Regardless of the existing fandom or the source material, adding onto a piece of media is a dangerous job. However, rather than adding to the end of the story that might already have been tied off nicely, many industries decide to tack on material to the beginning as a prequel.

When it comes to making a prequel, there are many different angles a movie production company can take. If the original story is set in some kind of magical landscape where a protagonist is led through a world by someone who has been there before, of course a prequel could feature the story of that guide or mentor. Examples of that can be seen through Sam Raimi’s 2013 Oz the Great and Powerful which served as a prequel to the classic 1939 The Wizard of Oz. Oz the Great and Powerful further gave a backstory to the Oz character who Dorothy and the others were sent to find. More recently, Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory has gotten its very own prequel in the same style as Oz with Paul King’s Wonka, showing the story behind Willy Wonka himself and how he came to be the man Charlie Bucket met all those years later.

Outside of this style, even more prequels keep the same protagonist but give them more depth or an origin to allow the audience to see why the character is the way they are. Disney Studios has a few films of this nature like Monsters University for Monsters Inc. and The Little Mermaid: Ariel’s Beginning which serves as a prequel for the original The Little Mermaid, although The Little Mermaid prequel was not made by the same studio that made the original.

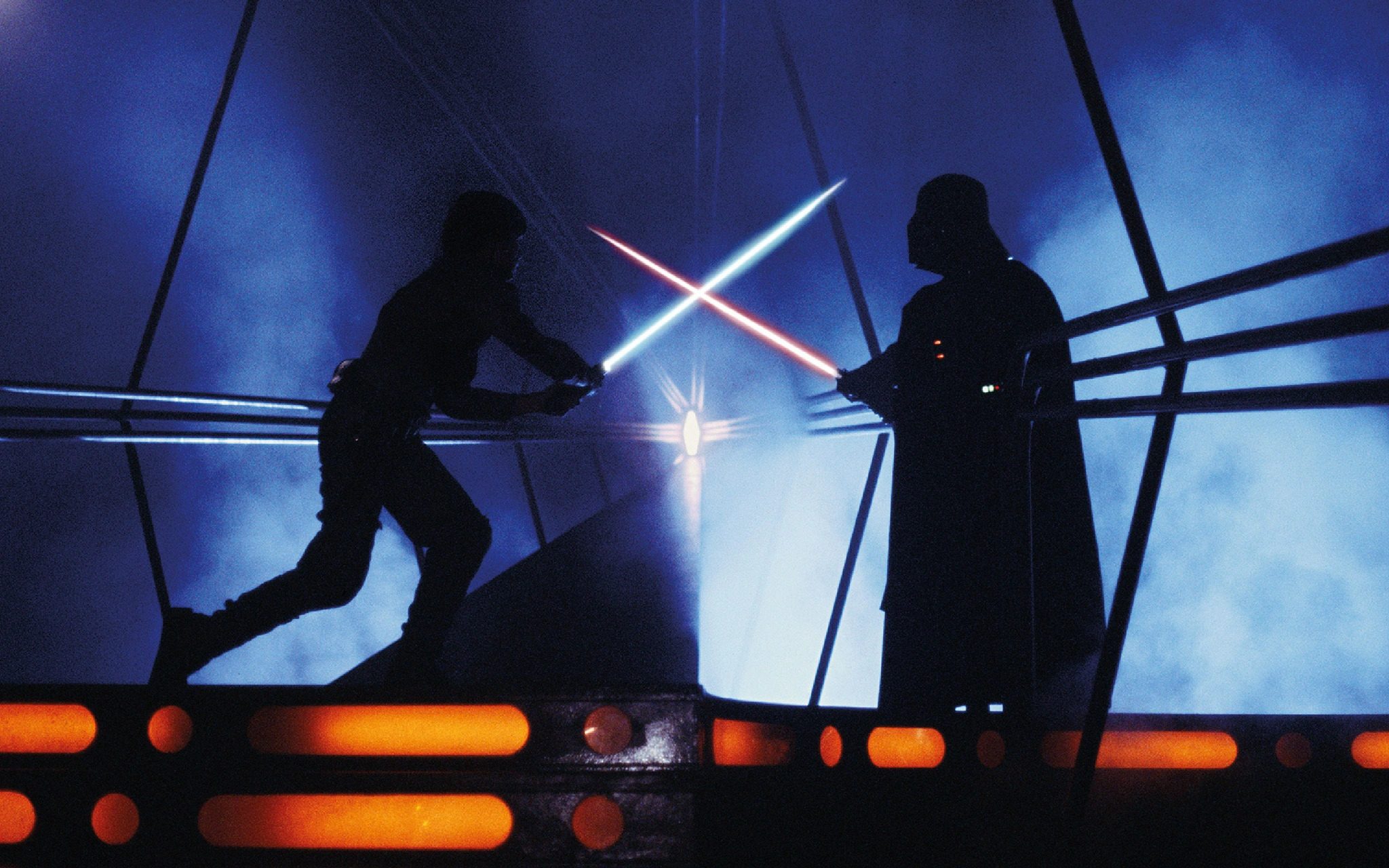

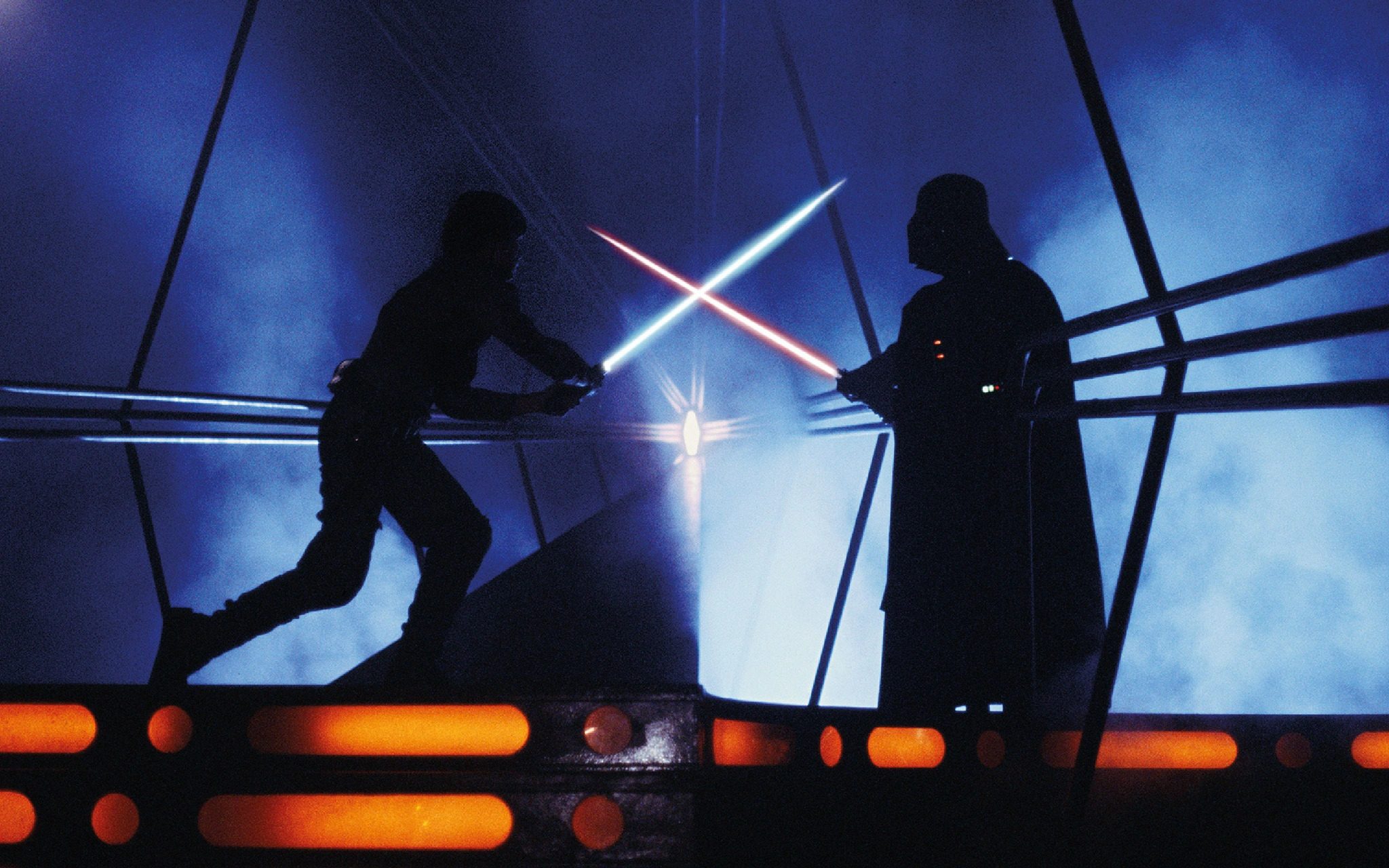

While all these prequels allow for worldbuilding and character development, no other style of prequel is quite as enticing as those focusing on the antagonist of the original story. Probably the most iconic example of a villain backstory style of prequel are the first three Star Wars films that came out from 1999 to 2005. The Star Wars franchise was set up deliberately with room on either end of the original trilogy which came out from 1977 to 1983 to have more of the story added on. The very first Star Wars installation was released as Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope without the existence of an Episode I-III until years later. However, how the story before we meet Luke Skywalker pans out was up to the creativity of the directors and producers of the series, namely writer and director George Lucas. While Lucas said that the prequels were created from a combination of the lore he had created surrounding the original three films, the decision to focus on Anakin Skywalker, one of the main antagonists in the later films was a stroke of genius.

The prequels give more context to and flesh out the government system of the Star Wars universe and introduce the audience more to many of the characters with smaller roles in the original series. At the same time, following Anakin’s perspective, being discovered and trained to be a Jedi knight just as his son would be many years later, the audience is allowed to see a much more human side of Anakin, his feelings and reasons for many of the things he did later on. While there were a whole host of factors that we can’t even pretend to encompass in one piece that led to Anakin’s transformation and turn to the Dark Side, the main root is Anakin’s fear, particularly the fear of loss and being too weak to protect those he loves.

Similarly, the most recent prequel that has been rocking the film world is the adaptation of Suzanne Collins’ latest installation, The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes. The original Hunger Games trilogy might not have required the existence of a prequel as much as Star Wars, but the world of The Hunger Games is complex enough and just far enough removed from our world that a worldbuilding prequel would never be turned down. Just like Star Wars, Collins chose to flesh out and humanize the antagonist of the original series, Coriolanus Snow. In a prequel that could have easily chronicled the days of the uprising or even followed the life of another tribute, the choice to make later President Snow our protagonist was really smart and kept the narrative fresh and exciting. Very similar to Anakin Skywalker, Corio’s most significant arc is focused on his obsession with a woman and the desire to protect what he values. The question of whether or not Coriolanous and Lucy Gray ever really loved each other can be debated in future pieces, but for now the certain fact of his obsession and desire to possess Lucy Gray is enough to make him a fascinating character and tie a parallel between him and Anakin Skywalker.

The goal of both the Star Wars prequels and Songbirds and Snakes is to initially humanize the antagonists of their original series and show them as more three-dimensional. We all love to hate someone, particularly when they dare to interfere with our beloved protagonists, but when the one we have hated for years suddenly becomes the new protagonist with some kind of tragic or relatable backstory, what then? Love is a very human emotion and is easily the most common theme of any film, TV show, or song. By painting a romance in the lives of both Corio and Anakin, the audience is much more likely to relate to or at least sympathize with them. However, even in these romances that they both foster, the toxicity and possessiveness of their characters also slowly become evident.

Anakin for instance starts as a very sweet kid in Episode I: The Phantom Menace. The audience only sees this boy who was dealt a rough hand but who still is powerful enough to have the chance to train to be a Jedi. However, they also recognize in him his fear of change and loss, something that worries the Council and causes them to initially reject him. It is this fear that they worry could eventually lead him astray. As a reflection, years later, Anakin’s son, our initial protagonist, Luke, teeters on the edge of that same fear when he goes back to save his friends. The support and strength that Luke can rely on to overcome that fear is what sets the two men apart. Showing that Anakin also struggled with the same things that Luke did years later, someone the audience is already sympathetic to, makes Anakin much more human and someone who could have been just as heroic as Luke under different circumstances.

Coriolanus similarly had the shadow of his father looming over his reputation. As one of the creators of the Games and a powerful political figure, Corio’s father was known as cruel and cold, doing anything to get to the top. Throughout the film, Tigress tries to keep Corio from growing into that same image, a task that the audience already knows she will eventually fail in. Even with this foreshadowing to the President Snow we have all come to hate, Corio’s charm and determination to help Lucy Gray, risking his neck on multiple occasions manages to still endear him to the audience. He is a bright and capable young man who has also not had the easiest life, causing us all to still root for him. Even so, Coriolanus’s selfish and possessive nature follows him through the movie in subtle ways that eventually accumulate in him being willing to kill the woman he had initially claimed to love to have himself come out unscathed.

The beauty and genius of antagonist-focused prequels is the knowledge the audience has going into it. We all know that sweet young Anakin will one day become Darth Vader and that charming Coriolanus will grow up to become President Snow and there is nothing in the narrative that can prevent that outcome. The villains we want so badly to hate are suddenly young and innocent making the audience second guess if they were evil at all. By humanizing the antagonists and showing the circumstances that led to their ‘villain arc,’ the audience has to sympathize with them and see the accumulation of events and the role models that played a part in making them who they are. At the same time, this style of film challenges the audience to question their moral code as they relate to and sympathize with a shady character. Does it make us terrible if we cheer when Corio finds Lucy Gray in 12? Are we also villains for hoping Anakin will prove them all wrong?

While both Anakin and Coriolanus are incredibly painted morally grey characters, they are still the protagonists of their prequel films causing the audience to have no choice but to relate to and sympathize with them through the story. Not only does this add so much more meaning to their character – thinking about Snow’s relationship with District 12 even before Katniss and Peeta’s games – but it also adds significantly more emotion to the original movies. We saw the relationship Anakin and Padmé had, no matter how toxic it was, how does that affect how we now see what could be running through Darth Vader’s mind in the iconic “I am your father” scene? Prequels of any kind add more depth to a world in many ways from simple worldbuilding to fleshing out the ‘original’ journey, but the telling of a villain origin story is by far one of the most enticing of them. How do you show a villain as a human? How does the audience feel about them now? Prequels are such an excellent way to humanize a character and turn them from simply a villain into a more complex individual, giving them emotions and a past that the audience is forced to sit with through the original story, questioning our morals and debating who is really a villain after all.