The Gangster picture represents one of the premier genres of 20th-century cinema. Its character archetypes, tropes, symbols, and themes permeate through all interpretations of the genre in the various waves of film. To be re-examined repeatedly with examples of the remarkable success, under different lenses, must mean that the ideas are on display through the imagery and presentation of the Hollywood gangster. From the Golden Age to New Hollywood and postmodernism, there must be something at the heart of characters like Rico from Mervyn LeRoy’s 1932 film, Little Caesar, that are housed in Vito, or Michael Corleone from Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather. Spanning decades, these protagonists embody the intersections of immigration and assimilation of Italian-Americans and capitalism, as the gangster steps outside the bounds of acceptable commerce to achieve the elusive “American Dream.”

This dream means many things for different groups of people over vast periods of time. Distilled, the American Dream is the concept of personal exceptionalism, both financially and spiritually, that can be found in America through the American capitalist system. Immigrants particularly embraced this idea during the early half of the 20th century, with work plentiful and a decent life somewhat tangible. Mervyn LeRoy was quick to critique this dream as unattainable and hollow in his foyer into gangster filmmaking. Still, as conditions deteriorated in the latter half of the 1900s, a sourness toward the American Dream took root, and with it, a distrust of capitalism and institutions. Along with Francis Ford Coppola down the line, LeRoy uses the Gangster genre to critique this idea in the endings of their films, which act as conclusions to thesis statements never quite stated explicitly in the preceding hours of the story.

In the Golden Age of Hollywood cinema, it was typical for a mobster protagonist to be killed at the end of their story to damn the character for all of their misdeeds and ill-gotten gains. This occurs in Little Caesar, after Rico, played by Edward G. Robinson, returns to the gutter but is detected by the police due to his crazed lust for his lost power. A squad car arrives to arrest him, and he flees behind a billboard advertisement. The police riddle it with bullets, and Rico is shot, with the height of the billboard obscuring his body. In his last breath, he utters, “Mother of mercy, is this the end of Rico?” Rico’s attempt to fulfill the American Dream in a manner unacceptable by the status quo, represented in the police force, is a failure. The advertisement placed in front of him as he dies acts as a reminder of the unstoppable momentum of consumer capitalism that has the ultimate influence in America, not the individual.

Throughout his rise to wealth in organized crime, Rico consistently remarks that he wants to be “somebody.” This motif underscores what Robert Warshow calls “the gangster as a tragic hero.” While wealth is undoubtedly a factor, it is simply a by-product of the fame Rico desires. Validation from the institutional elites, by way of the American Dream. His inability to create wealth for himself inside the established order of exploitative capitalism, but rather outside, thereby ripping the mask off the operation, makes him a threat and is what bars him from the validation of being “somebody.” According to Warshow, Rico’s final line of dialogue, “speaking of himself thus in the third person because what has been brought low is not the undifferentiated man, but the individual with a name, the gangster, the success; even to himself he is a creature of the imagination.” Rico’s view of himself as something greater than the average-joe in this sequence displays his desire to break into the higher classes of American society dominated by wealthy businessmen, who have rejected him for honestly embracing exploitation openly instead of hiding behind a thinly veiled facade of excellence as the reason for their success. Rico’s death, denied of the grandeur he would prefer and obscured by an advertisement, is a symbol of the machinery of capitalism that continues as a collective, despite the actions of any one individual.

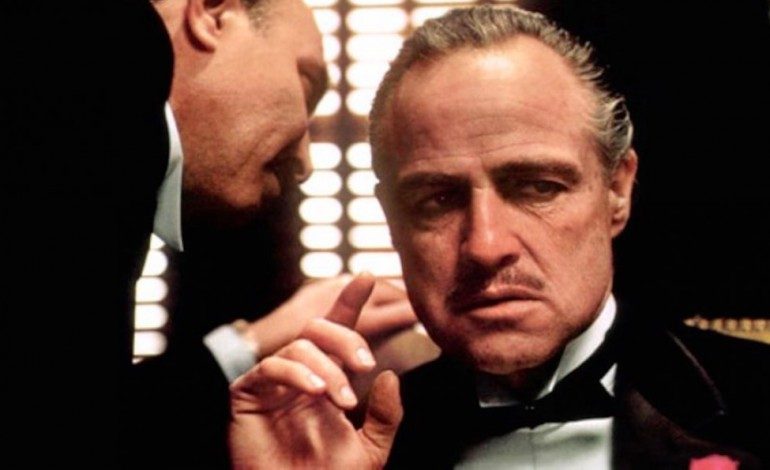

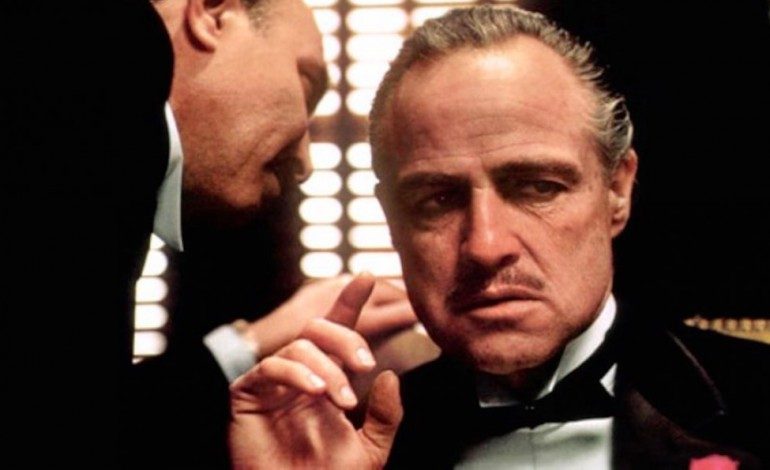

Francis Ford Coppola and Mario Puzo’s The Godfather (1972) offer an updated view of organized crime for a more skeptical age and audience. As a member of the “Film School Brats,” Coppola was among the first generation of filmmakers to go to film school and learn about how Hollywood cinema relates to American culture at large. Multiple times in the film, the characters refer to their operation as “the Family.” This is famously at the request of the Italian American Civil Rights League, who believed that the word “mafia” defamed the Italian-American reputation. This term is utilized in the film to denote an exclusivity to the Corleone business, which has now been accepted into high society, unlike in Little Caesar. This status is shown in the widely attended wedding ceremony in the film’s opening, the respect given to Vito Corleone, and the meeting of the five families, which resembles a boardroom meeting. This final example is set to the backdrop of a locomotive mural traversing the western United States. This evocation of the American frontier implies a correlation between the “Family” and the expanse of capitalism and business.

The American Dream is achieved in The Godfather by Vito Corleone but is shown to be hollow and built on exploitation, not unlike “legitimate” American corporations. This dream, however, is not open to all. The ending of the film, which features Michael Corleone, played by Al Pacino and now the head of the family, promising to inform his wife, Kay, played by Diane Keaton, just how they make their money. He implies that their income comes from non-criminal activity, but as Kay leaves, two Capos enter to speak with Michael and close the door behind them. She is left in the dark, knowing there is more to what her husband claims. This moment speaks to a greater distrust in the American capitalist project after the turbulence of the 1960s. In Chris Messengers The Godfather and American Culture: How the Corleones Became ‘Our Gang,’ he argues, “A case could be made that The Godfather’s climate of reception in1969 was in part dictated by that historical moment (patriarchy under severe stress because of the Vietnam War, collapsing American families, and generational conflict, a craving for law and order beyond compromised American institutions), but such hypotheses do not account for the kind of alternative Don Corleone and his family provide.” This observation is poignant, but the film makes an effort to show that the Corleone family offers no alternative to the status quo. The family’s business remains outside the acceptable bounds of commerce, but the affairs are tolerated and even embraced by the populace and many corrupt elites.

The ending casts Kay as the average citizen who benefits from the mafia’s activities but is ultimately excluded from its utilization. Michael Corleone makes dealings with his Capos behind closed doors, just as the populace has no control over the means of production. This final moment reflects the direction of the American Empire away from the human-centered social democracy of the New Deal and Great Society and towards a neoliberal capitalist country, prioritizing corporations over people and making these decisions without moral questioning. In A Class Act – Understanding the Italian-American Gangster, author Fred L. Gardaphé argues, “Vito enables the family to rise from poverty to riches, as their heir, Michael refines his father’s tricks of the trade to help the family thrive in a post-immigration world in which the trickster gains acceptance as an American businessman, but loses his family.” Michael’s dealings isolate him from family and the love that comes with it because to be successful under capitalism; one must put profits before people. Kay’s realization of Michael’s ulterior commitments speaks to the general unease of the late 1960s and early 70s that we are not the ones charting the course for the future of America. Therefore, the American Dream is realized in The Godfather but shown to be exclusive and immoral.

The final scene in films and works of the Gangster genre work as more overtly stated conclusions to the thesis statements sprinkled throughout the runtime. The moment makes a viewer see the bigger picture and ponder the events that occurred previously. The mobster is one of the more hardened capitalistic characters of the American experiment. The rejection by higher classes of elite society in the Gangster film makes their harrowing exploits somehow sympathetic. Their honest embrace of rugged exploitative capitalism makes them more honest than those who “earn” their wealth “legitimately,” namely CEOs and corporate managers. This placement of the gangster in each era of cinema, corresponding with each era of American society and economic structure, gives the viewer an idea of what the pursuit of the American Dream means and where it ultimately leads.