If you hate Superman, I don’t blame you. The comic book icon, heralded as the world’s first superhero, has long been criticized for his squeaky clean, uninteresting, Boy Scout demeanor, his seemingly endless laundry list of superhuman abilities that essentially make him immortal and thus remove any real suspense from stories placing him in peril, and his incessant ramblings about truth, justice, and the American way, which now feel woefully dated.

Decades of comic book tales, animated series, and movie serials have painted the character in this light, and it’s thus fair for most to assume that these are the qualities we’re supposed to enjoy about Superman. Indeed, many of the writers, artists, and actors who have presented him to the world likely appreciated these elements themselves.

The problem is that, especially in today’s world, it’s hard to celebrate these aspects of the character. At a time when events in America make it more difficult than ever to be proud of the country, and political leaders are choosing to exercise or not exercise their immense power in ways most cannot possibly justify or support, it is difficult to view a godlike being who spouts American ideals while self-righteously brandishing his destructive power as a hero.

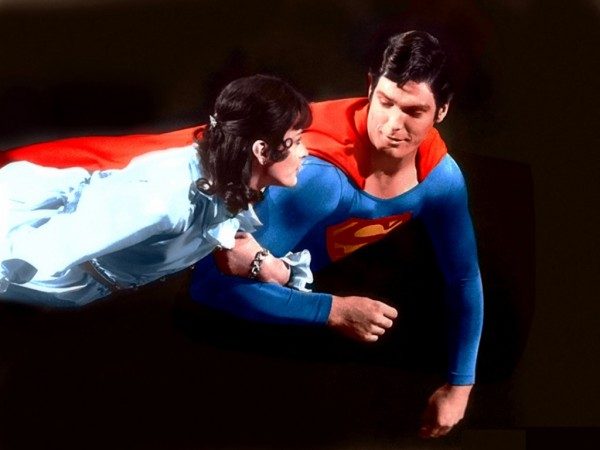

Yet one landmark film, made during another era when faith in American government was at its lowest, managed to capture the character from a new perspective, one that truly resonated with audiences. At a time when the closest thing to a superhero movie was the campy 1966 cinematic translation of the Adam West TV series Batman, a group of filmmakers decided to take a gamble by producing a big-budget, special effects-laden blockbuster that took a superhero seriously. Director Richard Donner’s 1978 megahit Superman succeeded for a variety of reasons, but the heart of the film that has kept it relevant for nearly 40 years is its star, Christopher Reeve.

Reeve was not a fan of comic books, nor of Superman, but perhaps this gave him an advantage in his performance. His portrayal of Superman stands out because he chose to approach the iconic character not as a square-jawed, two-fisted do-gooder or as a self-important god, but as a sensitive individual who, when it came to using his extraordinary abilities, worked hard to exercise restraint.

So as we celebrate what would have been Reeve’s 65th birthday (the actor passed away in 2004) during a period of extreme violence in this country, it is worth remembering how his Superman exemplified how forces of destruction can be sensibly controlled, and that gentleness and compassion are stronger forces than violence ever will be.

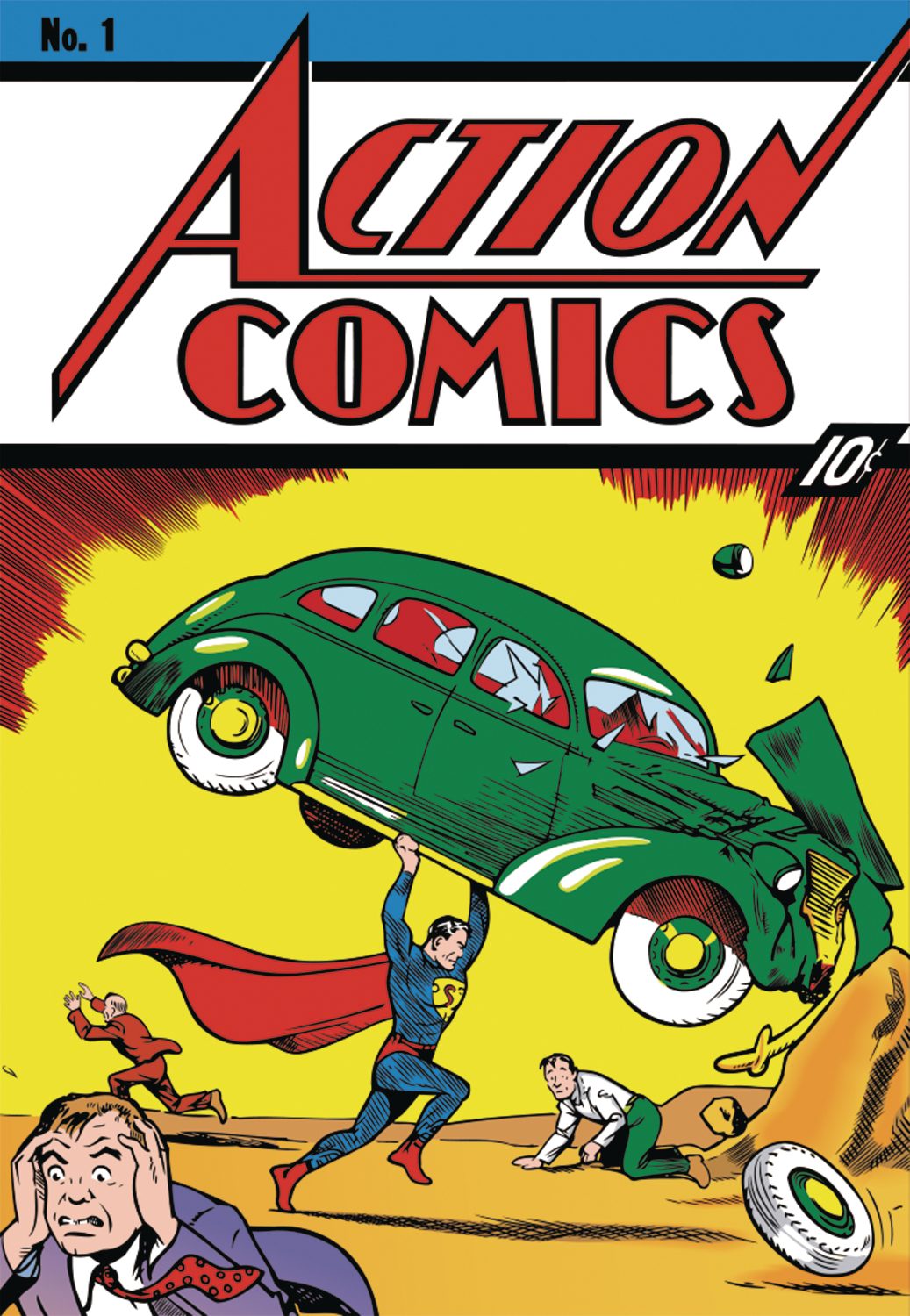

In order to fully grasp Reeve’s impact on Superman, one must look back at the character’s origin. Created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster in 1933, Superman first appeared on the cover of the appropriately-titled Action Comics #1 in 1938, lifting a smashed car over his head while bystanders ran away screaming in shock or, more likely, terror.

This memorable image epitomizes the initial approach to the character. Through the 1940s and 1950s, stories featuring the Man of Steel focused on his remarkable abilities, pitching him as an action hero ready to quite literally fight the good fight whenever evil reared its head.

The 1950s TV series Adventures of Superman, which starred George Reeves in the title role, was filled with scenes in which Superman smashed through brick walls and punched criminals. In fact, the show’s original producer was fired after the first season for making the program too violent.

Similarly, early Superman comic books had the character killing villains before it was decided that Superman shouldn’t be a murderer. Still, comic book writers continued adding new powers to Superman’s repertoire during the early years to make him an increasingly formidable physical force.

But by the late 1970s, the cultural attitude had shifted. Readers and viewers no longer wanted to see a superhuman being indiscriminately punching his way out of problematic situations. In the wake of Watergate and the Vietnam War, they wanted an accountable hero who understood the sense of responsibility tied to his powers and was able to recognize that the solution to violence is never more violence.

Richard Donner understood this, crafting a Superman film that would realistically reflect how the world would react to a costumed character with superhuman abilities attempting to take global peacekeeping into his own hands, and how such a being would go about achieving this task delicately and respectfully.

While the production initially sought out traditional masculine icons such as Robert Redford and Clint Eastwood for the title role, when they proved unavailable, Reeve, then a relatively unknown stage actor, was brought to London for a screen test. Reeve reportedly took time on the flight to the U.K. to think through how he wanted to take a different approach to Superman.

The way he saw it, the late 1970s had brought about a change in the masculine image. It was now socially acceptable for men to express vulnerability and gentleness, and Reeve felt that the new version of Superman should reflect this cultural shift.

His thoughtful and timely take on the Man of Steel made a strong impact during his screen test. Though Donner felt Reeve was too skinny for the role, he was blown away by the young performer’s audition and cast him anyway. Reeve then spent two months bulking up under the tutelage of former weightlifting champion David Prowse, who a year earlier had played the man in Darth Vader’s suit in Star Wars.

Despite his eventually imposing physical presence, Reeve maintained his commitment to highlighting Superman’s sensitivity in every element of his portrayal. In Reeve’s eyes, Superman, as an alien sent from his dying homeworld to protect the people of Earth, would still view himself as an outsider looking in.

As the movie reveals, Superman understands the destructive and disruptive potential of his powers from a young age. Rather than exercise said powers excessively, he seeks to understand and respect humanity. Thus, he chooses to leave the humans to sort out their own issues and only intervene when the situation becomes dangerously serious.

In other words, Reeve’s Superman is an exercise in restraint, and this shows through in practically every scene in the film. When Superman flies to reporter Lois Lane’s apartment for an impromptu interview, Reeve sheepishly apologizes for startling Lois and then proceeds to patiently stand with his hands calmly clasped in front of him. This non-threatening pose stands in stark contrast to George Reeves’ classic hands-on-his-hips power stance from the 1950s TV series. Even the way Reeve pulls Lois’s chair out for her before taking his own seat at her table and delicately tossing his cape to the side to avoid sitting on it reflects a reassuringly gentle humility.

It becomes clear as the film progresses that though Superman is wildly powerful, aggression is simply not in his nature. Reeve almost never raises his voice, even when speaking with his archnemesis, Lex Luthor.

Arrogance doesn’t seem to be in his DNA either. When asked if he’s impervious to all pain, Reeve smiles and replies, “Well, so far,” as if suggesting that surely there is something out there stronger than Superman, but he hasn’t encountered it yet.

Due to Reeve’s portrayal of the character, Superman’s secret identity, mild-mannered Daily Planet reporter Clark Kent, thus serves as not just a performance designed to allay suspicion of his superheroic efforts, but as a guise through which Superman can experience humanity non-disruptively and also minimize his use of force to effect positive change in the world.

When Clark and Lois are mugged by an armed criminal in an alley, Clark waits to take any physical action and instead tries to calmly reason with the thug, hopefully remarking, “You can’t solve society’s problems with a gun.” His efforts predictably fail and he is forced to use his powers to catch a bullet from the criminal’s pistol, but the fact that he tried to talk things out with the thief first is as admirable as it is ridiculously naive.

This is perhaps the most brilliant part of Reeve’s performance as Superman. He makes every effort to avoid using force to solve problems, instead attempting level-headed, diplomatic solutions at every turn and only relying upon his powers as a last resort. His restraint in using his powers, rather than the powers themselves, are what define him as a hero. This is admirable in itself, but Reeve also recognized that in this way, Superman hopes to serve as an example to world leaders on the brink of nuclear war.

It’s as if the most powerful weapon of mass destruction in history crash landed on Earth and simply refused to detonate, preferring to serve as a physical example of responsibility. While he may have the power to destroy anyone or anything he likes, Superman chooses to exercise his power in the most limited way possible, only using it so as to prevent crises and help others. He knows that he has the responsibility to act in this manner (as Uncle Ben would eloquently detail in the Spider-Man movies decades later).

Perhaps Reeve said it best in an interview to promote the 1987 sequel Superman IV: The Quest for Peace, a project on which he contributed to the story. When asked why he wanted to return for a fourth Superman film, Reeve stated, “It’s fun entertainment that has an actual character at the center of it…a character who’s caring, who loves people, who’s considerate, and who’s a gentleman, as a possible antidote to the Rambo’s and the Chuck Norris’s and the Schwarzenegger’s.”

The tail end of this statement refers to the hyper-violent action films of Sylvester Stallone, Chuck Norris, and Arnold Schwarzenegger that dominated the cinematic landscape in the 1980s. Reeve went on to proudly describe how in nearly every one of his Superman movies, not one person dies. He believed in Superman as an icon of peace and peaceful conflict resolution, and in many ways this is what the character came to embody thanks to his portrayal.

The actors who would go on to play Superman after Reeve followed his example. Brandon Routh based his bumbling Clark Kent and soft-spoken Man of Steel in 2006’s Superman Returns directly on Reeve’s portrayal, which he says he watched as a child. Even Henry Cavill, in his edgier, moodier performance as Superman in Zack Snyder’s recent DC Entertainment films, serves as the level-headed voice of reason in contrast to Ben Affleck’s off-the-rails, violently vengeful Batman.

The true depth of Reeve’s own heroism was later revealed following a tragic horse riding accident in 1995 that left him paralyzed from the neck down for the rest of his life. He co-founded a leading spinal cord research center and created the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation to raise funds for spinal cord research and to better the quality of the lives of individuals with disabilities. While he tragically died in 2004 at the age of 52, Reeve’s advocacy and fundraising efforts continued to make an impact.

His iconic role also had far-reaching effects, impacting the approach that virtually all directors, writers and actors would take when making the superhero blockbusters that have now become modern classics. Responsibility and damage control have been the main focus among cinematic superheroes in recent years, and characters like Chris Evans’ Captain America continue to be played with the same sense of self-deprecating humility and calmness that Reeve brought to Superman.

Kevin Feige, the president of Marvel Studios, has even admitted that Marvel’s creative powers-that-be gather to view Reeve’s original Superman film before starting work on each new project, as they consider it the template for a successful superhero film.

Today, it’s easy to look back at Reeve’s Superman as an idealistic and corny hero, one who lacks Deadpool’s naughty sense of humor or the edgy darkness that consumes Batman. But there’s something mercifully reassuring about extraordinary powers being entrusted to such a compassionate, gentle and determinedly peaceful individual.

His Superman may be faster than a speeding bullet, but he’s far less likely to brag about that fact than to calmly lecture you on why that bullet shouldn’t have been speeding anywhere in the first place. That’s a lesson that particularly hits home this week.

Perhaps now more than ever, Reeve’s Superman serves as an example of how the capacity for destruction should be restrained and controlled at all costs, rather than exercised freely. Knowing what Superman’s capable of makes us, as an audience, feel especially lucky that such abilities were granted to someone like him and not to some sort of aggressive tyrant (like General Zod, the villain in Reeve’s second superhero outing, Superman II). Reeve’s Superman may still be a Boy Scout, but it’s the sensitivity he displays and his choice to value peace over acts of force that make him interesting to watch, and that we as a society can certainly take a hint from now.