So, uh, you guys ready to have another conversation about Spider-Man? Because we’re kind of – okay, hang on, hang on. I can already hear you groaning and beginning to click out to another tab. I know: “Again with the Spider-Man? Can’t we give it a rest with this guy already?” Look, we get it. The amount of behind-the-scenes drama revolving around this character’s representation that has been making it to the news lately is more than a little absurd, and the media coverage is starting to feel like a broken record. But, for better or worse, the past few months in general and this past week in particular have had a lot of weird turns and revelations that do merit a bit of scrutiny, particularly because of what they say about institutional practices about minority representation.

So basically? Yes. Again with the Spider-Man.

In case you missed this news item, on June 16th Wikileaks made the entirety of the correspondences, documents, and various other pieces of media from the now famous Sony Online Hack available for public consumption. A few days later, various news sites began reporting on the contents of a licensing agreement between Sony Pictures (the current license-holders for the character, and the makers of both of the Amazing Spider-Man films) and Marvel. What was particularly interesting was a rather strict set of parameters that had to be followed in the representation of Spider-Man’s character. Notable among these: Spider-Man does not kill except in defense of self or others, does not abuse alcohol, gains his powers from being bitten by a spider while attending either Middle School or College, (but not High School apparently) and loses his parents early on in his life. (among many others) But it’s one particular bullet point that has been getting the most flack from various commentators: Peter Parker, the agreement spells out, “is Caucasian and heterosexual.”

Before we go any further, yes, there has been a degree of sensationalist overstepping to the various “Spider-Man Must Be White and Straight!” headlines that have spread throughout the Internet in the past few days. The actual wording of the agreement comes with a bit of nuance and lawyerly wiggle room built into it. The exact phrasing is closely tied to Peter Parker, not Spider-Man in the wider, more archetypical sense of the word. So theoretically you could go ahead and still make a film starring one of the other characters that have donned the iconic costume, like Miles Morales or Miguel O’Hara, it’s just Peter Parker they are contractually obligated to keep Caucasian and heterosexual. Which is… nice, but doesn’t really offer a whole lot of comfort in the most utilitarian of senses. There are hardcore fans of the Marvel Cinematic Universe who have no idea that Miles Morales even exists, but you know who’s aware that Peter Parker is Spider-Man? My octogenarian grandmother who doesn’t speak a word of English. For the vast majority of the public, Spider-Man and Peter Parker are interchangeable terms, and that’s kind of the end of the story.

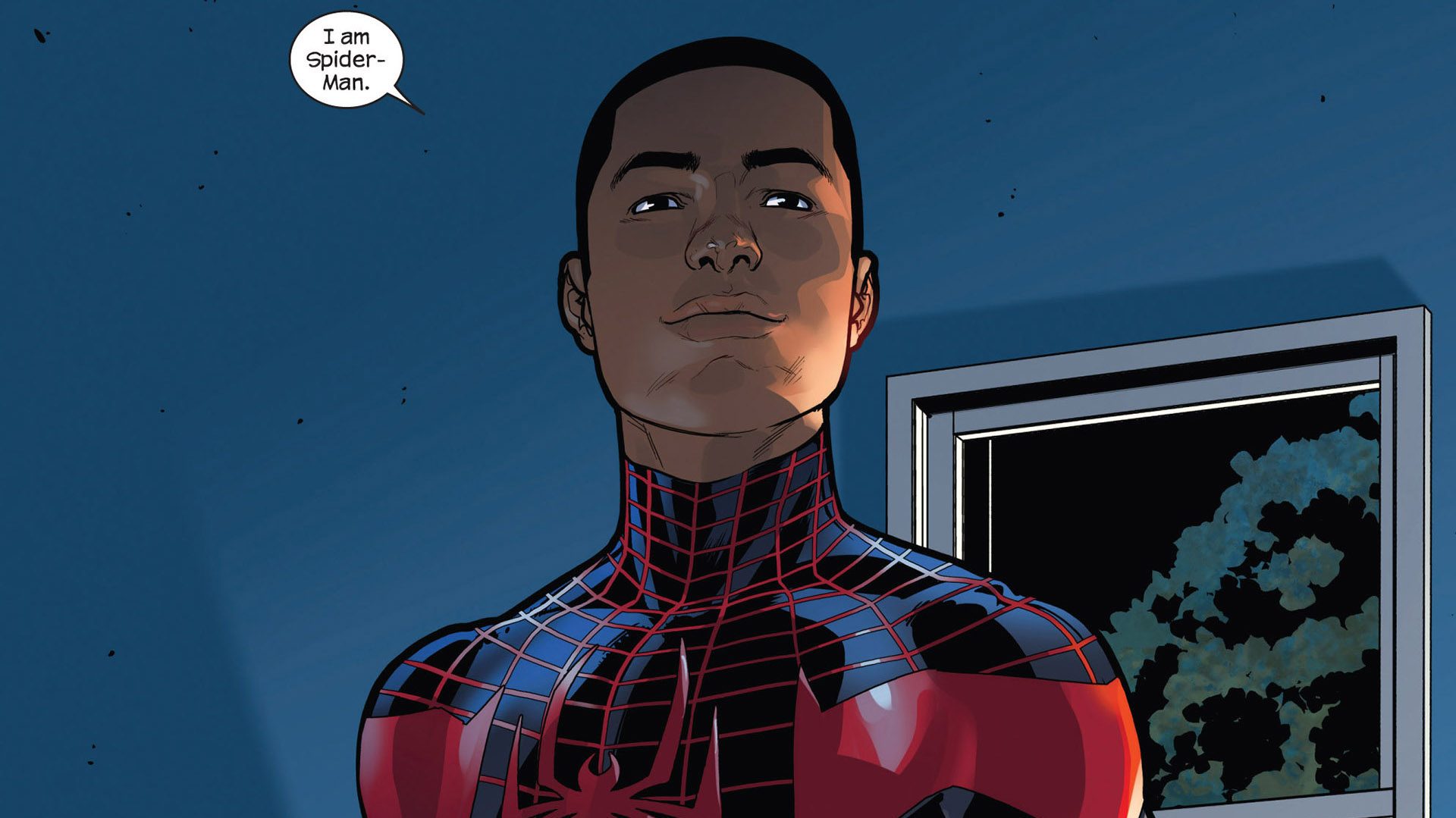

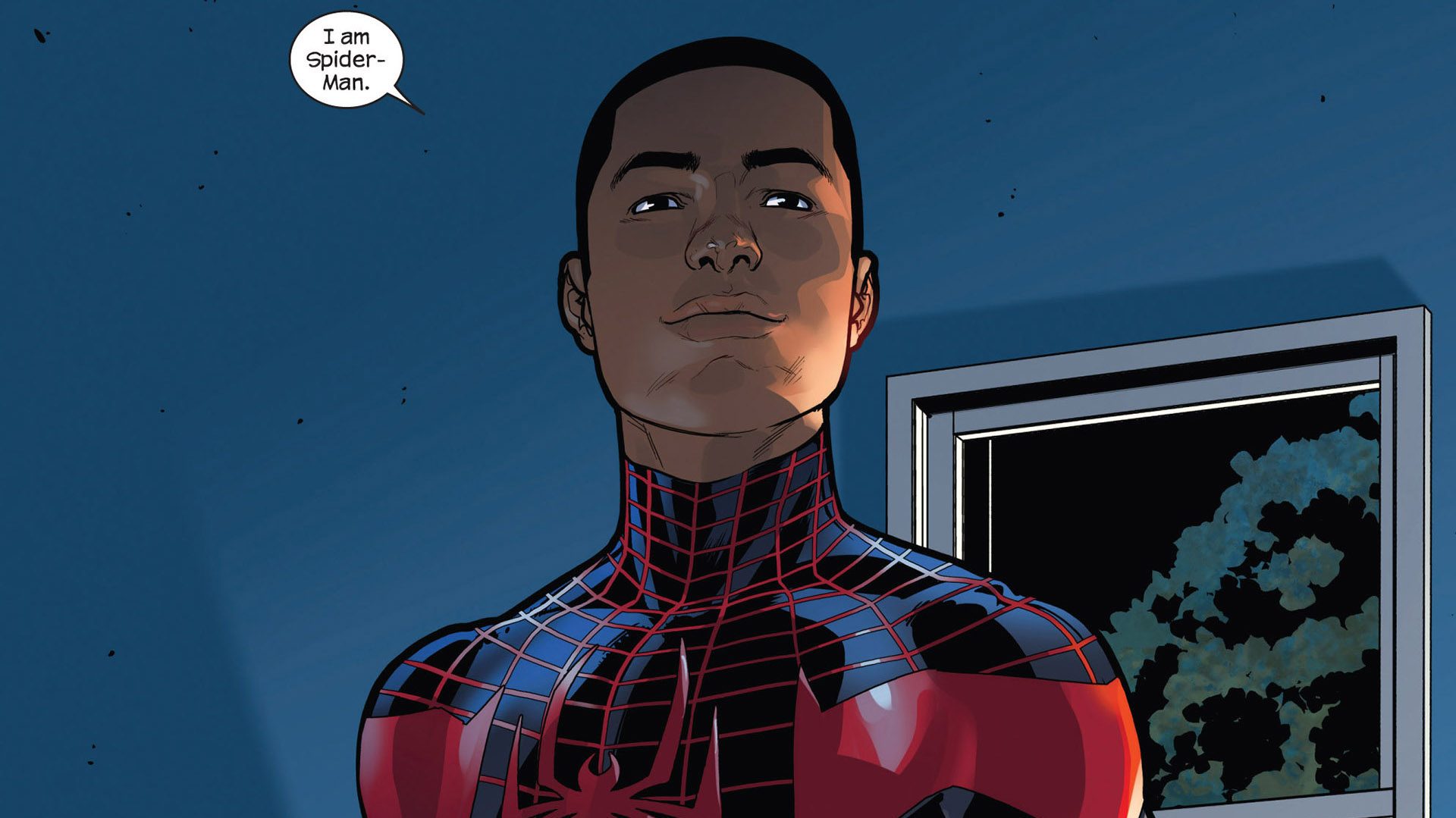

Miles Morales, the Spider-Man in Marvel’s Ultimate Comics series. A character of both African-American and Latino ethnicity, Morales was partly inspired by both President Obama and the campaign to get Donald Glover cast as Peter Parker in 2012’s ‘The Amazing Spider-Man.’

Now, what’s really been interesting about this whole debacle is seeing a very particular kind of reaction pop up on various outlets, one that basically amounts to, “Oh c’mon, how is this a problem? Why are we even talking about this?” The argument says that Marvel has a right to protect the material of their brands and their characters, and to ensure that the movie-going audience gets a story that at least resembles the one from the comic books. Measures like this are in no way harmful, they are just there to ensure that in translating the property into movie form the filmmakers still end up with something that looks, sounds, and feels like Spider-Man.

I am very much on the other side of that issue, and it’s hard for me to see the fact that these sorts of storytelling, character, and, yes, casting restrictions are hardwired into Spider-Man’s cinematic presence as anything other than a bad thing. Now, don’t get me wrong here – I recognize that Peter Parker is a fictional character, with no objectively accurate form of the character that needs to be portrayed. If Sony and Marvel want to make movies starring nothing but heterosexual Caucasian males for the next 50 years, well, that may make some people disgruntled, but I don’t think you can make an argument for it being wrong. Heck, I’m not even saying that the next iteration of Spider-Man should be a person of color and/or a member of the LGBTQ community. I’m not a fan of casting a minority performer in a preexisting role just because we have the option. But you know what I’m even less of a fan of? Not having the option. In other words, I don’t have a problem believing that a Caucasian actor is the best option to play Peter Parker, but I sure as hell do have problems with people who don’t fit that description not even being taken into consideration.

New Spider-Man actor Tom Holland, accepting the ‘Best Newcomer’ Award at the 2013 Jameson Empire Awards.

To wit, I like the recently unveiled choice of Tom Holland, the up-and-comer who made his name on the stage of Billy Elliot the Musical and as the eldest son in The Impossible, for Peter Parker. I like that he’s already an acclaimed stage presence even though he’s only seventeen. I like that he’s someone with a strong dance background and a history of performing through the physicality of his entire body. I like that he can do a backflip like a total boss. I think it’s a very sound decision – it just feels less so when I know that the strengths of, say, Dear White People’s Tyler James Williams, Game of Thrones’s Jacob Anderson, and Community’s Donald Glover were in no way relevant to the deliberations.

Part of what’s hilarious about this is that, even if you take the optimistic view that they exist as a way of preserving the integrity of Parker’s character, these character prerequisites may end up doing more harm than good to the cause. In a classic case of missing the forest for the trees, these norms preserve a lot of the surface signifiers of the character and never stop to think how deviating from them might better serve some of the most fundamental or deep-rooted parts of the ethos. Consider this for instance: part of Peter Parker’s persona is his underdog status, the fact that he is constantly beat and trod upon. Are you telling me that there’s nothing to be gained by seeing that side of the character through the lens of a minority or LGBTQ experience? Would that not perhaps lead to some poignant and eloquent insights into the character’s experiences? This isn’t that radical of an idea – plenty of theorists and commentators have already drawn the metaphorical connections between the closeted “secret identity” aspect of comic book heroes and the hardships endured by members of the LGBTQ community. Or is seeing some high school bullies beat him up because he’s kind of a dweeb still the more compelling alternative? I don’t think it’s completely unthinkable to imagine that a version of Peter that on the surface looks unfamiliar might be a superior way to examine, engage, or reenergize the themes and conflicts he embodies.

There’s even some credence to the idea that by changing one or two major attributes you can actually cast every other part of the character into sharper relief. Want some precedent? Look no further than D.C.’s 2003 special event series Red Son. In this retelling of the Superman story, we get to see Clark Kent’s origin with one major wrinkle: instead of crash-landing in Ma and Pa Kent’s Kansas farm, the Krytonian space-pod lands in a Soviet Union collective farm. Rather than growing up to stand for the freedoms of the American way, Superman is instead raised to fight for socialism and Uncle Josef. And you know what? Weird as it sounds, when it comes to insight about who this character is, it’s one of the most insightful things you will ever read. By taking all of the overly patriotic and jingoistic aspects that dominate Superman’s surface and putting them on mute, the book is able to draw the audience much deeper into the guy’s psychological processes and internal conflicts. Because the character is so iconic, since we already have a clear picture of him in our heads, presenting a version of him where one major attribute has changed allows you go much deeper with all of the things that stayed the same.

And really, the worst part of all of this is that even the argument of preserving Peter Parker’s character kind of rings a little hollow once you remember all of the crazy crap that they’ve done to him in the comics continuity. Sure, making him black or gay might be a departure from the baseline identity, but is it really that radical of a change? It’s not any weirder than that time that he was a noir vigilante during the Great Depression, and that’s a thing that totally happened. It’s not any weirder that that time he got doused with Gamma radiation, became the Hulk, and killed Iron Man, and that’s also a thing that totally happened. It’s especially not any weirder than that time that he was put under a curse and transformed into a monstrous spider being that guarded a mystical forest, and – yes, even that – is a thing that totally happened. So just to be clear… all of that is completely cool, but God forbid his ethnicity or sexual orientation ever change, lest we are left with a character beyond all recognition.

Iconic characters, just like film genres, change and evolve over time. They are created, they thrive, they become over-formulaic and obsolete, and, if they are lucky, they are eventually reinvented. Radical re-imaginings and re-conceptualizations are the evolutionary leaps that keep characters that have been around for over half a century interesting and relevant. It’s a reflection of the fact that times change, and social, cultural, and personal values shift and progress along with them. Attempts to preserve a character’s continuity may be a valiant effort, but it can also be the kind of thing that keeps one of the most popular superhero icons of contemporary times a product of the 1960’s. I’m not sure if Peter Parker should be a person of color or an LGBTQ person. Maybe he should, just like maybe James Bond should be played by a black actor or maybe the Doctor from the BBC’s Doctor Who should be played by a woman. These are all conversations that are worth having as new artists tackle the characters five decades after their original creation. The point of all of this, however, is that, back when they were created, having these heroes by a Caucasian, cisgendered males was the only choice. Maybe it is still the correct choice, but that should be the result of careful consideration, not the consequence of a contract continuing to make it the only option.