Marie Antionette does not inherently set out to be a feminist film, but can it be considered one anyways? The film itself is a historical narrative of girlhood, which depicts the lavish life of luxury that the royal family indulged in while focusing primarily on Marie and her story. This tale of girlhood and its interesting contextual foothold is what makes this film feminist, as it represents young adulthood and teenagehood from a female perspective.

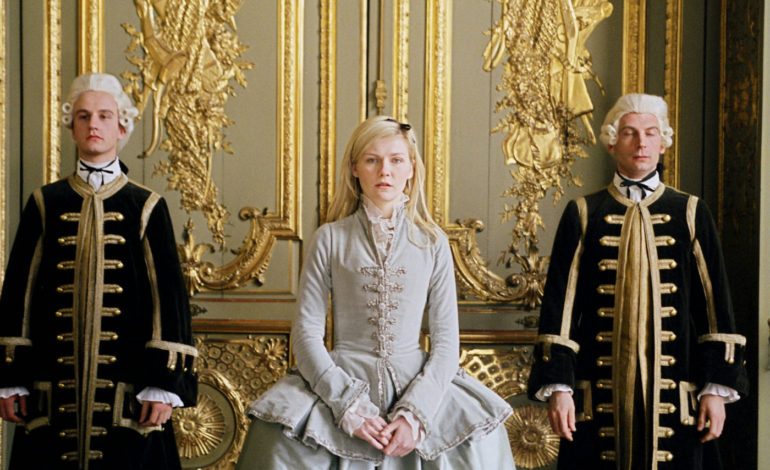

The narrative of Marie’s life starts out when she is just a teenage girl and her marriage to Louis of France is being negotiated. She is sent to France as his wife as a means of strategically aligning the France with her home nation of Austria. In her passing into French territory, Antionette is forced to give up all relics of her home country in favor of the new, even being forced to sadly relinquish her puppy Mops at the French border. After the wedding between Marie and Louis, their wedding night remains unconsummated, rallying up plenty of gossip and ill-will from the courts. The two remain untouched by one another for a long time after their initial wedding night, with many people singling out Marie as a flawed spouse and failure for not producing a proper heir to the throne. Instead of putting all her attention into her dismal marital life, she begins gambling, partying, drinking and consuming to fill her time.

After sneaking out to attend a masked ball in Paris, Marie and Louis return to Versailles to discover the king has fallen ill with smallpox. He soon passes away, leaving the young couple suddenly in charge of the nation’s fate. Louis and Marie are crowned king and queen of France, with Marie being only 18 years old. After a visit and guidance from Marie’s older brother, the young couple has sex for the first time in their marriage, quickly producing a baby girl named Marie-Therese. After giving birth, Marie spends much of her time with her daughter at a chateau on Versailles property, feeding animals, gardening, and spending her time doing much more wholesome things than she previously did in her younger adulthood. While she spends leisurely afternoons at her private chateau, it is clear that the rest of France is slipping into financial turmoil, as meetings with Louis’ advisors reveal that France’s backing of America in their revolutionary war is costing France a great sum of money. The film ends with a singular shot of Marie’s bedroom having been broken into and destroyed by French protesters who grew outraged at the royal family’s exuberant wealth.

From a very basic perspective, this narrative has very little to do with feminism, at least explicitly. It doesn’t try to be some feminist glory story, to deal with the politics of gender, or challenge many norms that are already in place. However, it can arguably be considered feminist for its interesting and dimensional portrayal of girlhood in the context of a historical piece; a perspective that is not often found within the history genre, as much of these films tend to focus on men and their accomplishments.

The portrayal of Marie’s girlhood is obvious from the minute that the film starts, as she clutches her beloved puppy and gives awkward hugs in her naivety. She is clearly a very innocent royal girl from Austria trying to make a good impression on those who she does not know the social norms to address. It is devastating to the young monarch when her puppy is taken away. This scene is exemplary of exactly how innocent and young Marie’s character is supposed to be portrayed as.

Her girlhood is exemplified throughout the rest of the film in much less innocent of ways, as she transitions into being a young adult. As she grows restless by the routine and monotony of palace life, she indulges in the finer things including fashion, desserts and champagne. Her indulgence in such delicacies are also indicative of the girlishness of the film’s main character- she is like a child in a candy shop who simply wants to enjoy life. At the time of her most noteworthy indulgence, her eighteenth birthday party, she is still a teenager, proving just how insanely young the lead is and at what point she is at in her journey toward adulthood.

Watching the coming of age of a young, yet influential, woman in the context of a historical drama is a perspective that is rarely pursued in Hollywood film. This approach to telling history, in combination with the portrayal of girlhood featured throughout the narrative, is precisely what makes the feminist messaging of the film shine through. The viewers are able to see Marie Antionette from a very intimate perspective, unlike any other retelling of her life story, showing her for the human being she was, rather than rejecting her humanity and depicting her as a one-dimensional figure head. We see the soft and vulnerable sides of her personality, not the cruel and twisted ones. This perhaps paint her as a slightly more forgivable figure in history than she actually was, but nonetheless the film definitely captures her humanity more accurately than many other media representations.