Huh. Well that was unexpected.

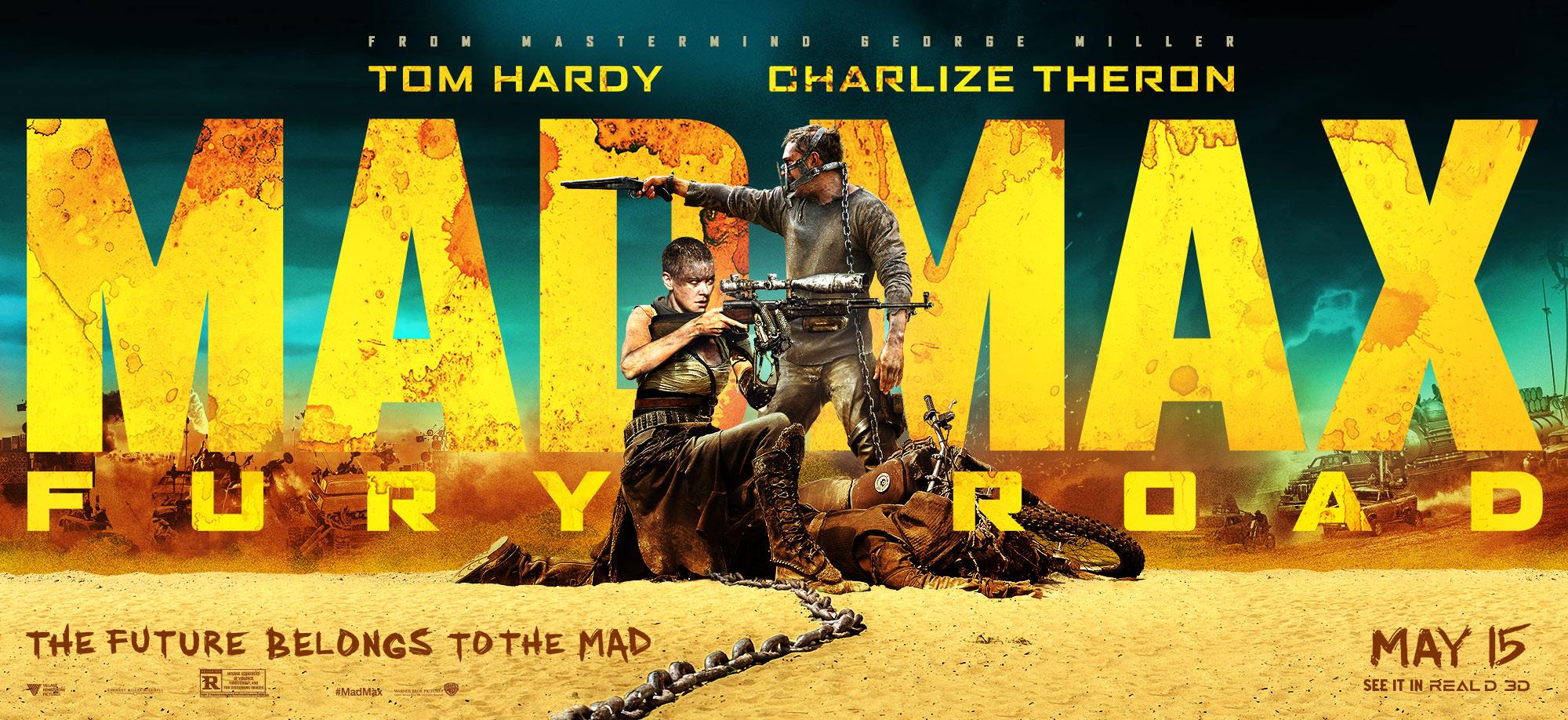

Mad Max: Fury Road opened in America on May 15th after a long and troubled production that went on, in some way, shape, or form, for over seventeen years. The film, the fourth in the post-apocalyptic series masterminded by Australian director George Miller, started gestating around 1998, undergoing an abortive start of production around 2001 and various major changes in cast, script, and direction before finally starting principal photography in 2012. This film had all the signposts of a painful failure: a soft reboot of a long (as in thirty years) dormant franchise, with its main iconic role recast and an intensive hibernation period in development hell. Well, pick your jaws off the floor everybody, because this troubled franchise has roared back to life, earning critical acclaim, a 98% rating on Rotten Tomatoes (that’s better than almost every film in the Academy’s Best Picture roster for 2014, for anyone keeping score), and a standing ovation from both die hard fans and newcomers…

… and that’s not even the most surprising thing that’s come out of this movie’s release.

No, the really shocking thing is a conversation we’ve all started to have in the wake of the film’s release about feminism and Western filmmaking’s depiction of female characters. In a preemptive act of protest that backfired so completely that I have to wonder if it wasn’t some genius promotions strategy thought up by the Don Draper of guerilla marketing, a small but loud group started speaking out against the film for its perceived agenda of evil feminist infiltration. As detailed in posts on various Manly Man’s Men websites such as Return of the Kings, the issue was that the film was positioning itself as an insidious bait and switch: pretend that it’s a movie about dudes driving fast cars and making large things go boom, but actually be a propaganda piece designed to brainwash the innocent masses into men-hating zombies.

(And the fact that Vagina Monologues author Eve Ensler was a consultant in the film just added insult to perceived injury.)

Writes Mr. Aaron Clarey, a self-described resident of the manosphere:

“This is the vehicle by which they are guaranteed to force a lecture on feminism down your throat. This is the Trojan Horse feminists and Hollywood leftists will use to (vainly) insist on the trope women are equal to men in all things, including physique, strength, and logic. And this is the subterfuge they will use to blur the lines between masculinity and femininity, further ruining women for men, and men for women.”

Who’d want to see that?

Turns out the answer is “a whole lot of people.” While there have been some who have doubled down on the calls for boycott that these men-focused groups issued before the release of the film, a lot of other folk’s reaction to these articles was a raised eyebrow and an intrigued mutter of, “Feminist Trojan Horse, eh?” The film gathered a lot of attention amongst feminist media groups, liberal-leaning movie-goers, and various political commentators; attention that seemed to double when all of these people saw the film and loved it, particularly its treatment of women and the development of Charlize Theron’s leading role as Imperator Furiosa.

Couple that with the fact that the film’s release came right between widespread discussion of women’s representation and sexual violence in Avengers: Age of Ultron and widespread discussion of women’s representation and sexual violence in a recent episode of Game of Thrones, and suddenly Fury Road stood as a towering ideological giant of enlightenment. And that is how the most positively-talked about mainstream feminist film in years is also the car chase movie that features a rock band car headlined by a blind guitarist who uses his flamethrowing, twin-necked guitar as a weapon.

Once again: huh. Not saying any of this is bad, but… huh.

All of this begs the question: what is actually going on in this movie? Is it worth all of the ink and pixels that have been spilled in talking about this movie? Is Fury Road really a feminist masterpiece, or is this just a case of the planets aligning just in the right way for this conversation to spiral into something much bigger than it should have been? Perhaps most importantly: are those original articles right? Does Mad Max: Fury Road really have this insidious agenda of luring a movie-going public in with the promise of mindless violence only to then smuggle in discourse about female representation and women’s takeover of action films? Those last two questions are very silly things to ask, but let’s go ahead and answer them anyway:

Yes. It absolutely does have that agenda. Through and through.

Now, where the opinions of the authors of the original pieces diverge from my own is that I believe this to be a very positive thing. Not just because I personally align politically with what we perceive the film to be doing – although, cards on the table, I do – but because I think that the film is exceptionally good at dramatizing this process and these ideas. Fury Road never gets on a soapbox to deliver a five minute monologue, aimed at the audience, about how men and women are equal or how someone owning someone else is a terrible thing. The film clearly holds both of these ideas to be correct, but it incorporates them into the telling of its story and lets the characters’ actions do the talking. The film has politics, but is never political. That may seem like a subtle distinction, but I think it’s a crucial one.

Here’s another example of a film that has politics without being political: Ridley Scott’s Alien. It’s possible to watch and enjoy Alien without having any thoughts about what is being said about the role of maternity in society or about sexual violence. The film doesn’t fall apart if you’re not thinking about these things on a conscious level – it still works as a piece of horror filmmaking because it is brutally creepy, paced with suffocating tension, and superb at atmosphere. You can also watch it and notice things like the phallic design of the alien, the analogy between the facehuggers and forced sexual contact, the birth metaphor with the chestburster, et cetera. But, and here’s the key, even if you’re not thinking about these things explicitly, the film aligns you emotionally on certain matters. Everyone who watches that film is horrified at the thought of something going into your body without permission and leaving some piece of itself behind. The filmmaker transmits his politics without ever having to make an overt political statement about rape.

Fury Road operates on the same level. It’s completely possible to view the film without thinking about it as a feminist diatribe and not have it fall apart. It doesn’t need to engage you on that intellectual scale to feel like a satisfying experience – it justifies its own existence by being suspenseful, and funny, and having a friggin’ rock band car with a flamethrower-wielding guitarist. If you come out of Fury Road and all you got was high-octane car chase film about Tom Hardy and Charlize Theron helping a group of scantily clad supermodels do a daring prison escape, you probably had a totally satisfying filmgoing experience. And that’s great.

But then stop and think about the details of what the film gave you and how it guided your emotions. What are the bad guys in the movie like? They’re car junkies, gun nuts, and body builders. They’re warriors and rock and rollers. They have good strong Viking values, like looking forward to death in battle and rebirth in Valhalla. These are all the accouterments of, if not a typical action movie macho man, at least a heavy metal rock God. The movie stacks the deck by giving them as many superficial signifiers of masculinity as it possibly can. And then it makes them all barbaric wretches, with disfigurements, debilitating illnesses, and disgusting malformations to go around. The film doesn’t ever have to say anything bad about these overtly cartoony examples of over-commitment to the patriarchy – it gets its point across simply by making them so viscerally gross that you as viewer literally want them to go away.

The exceptions to this rule are the characters of Max (played by Tom Hardy) and Nux (played by a barely recognizable Nicholas Hoult) who emerge as the only sympathetic male figures in the film. Max is an outsider to the conflicted world of the film, and it’s this very attribute that allows him to be a positive male figure. Sure, he’s not a card-carrying member of the Desert Amazonian lobby, but he’s also not a brainwashed servant to the barbarian patriarchy. He doesn’t makes choices based on an ironclad ideological agenda or a pre-existing allegiance to any group; he makes them based on his internal moral compass, personal sense of right and wrong, and past experiences. The fact that he’s a man is never a problem because the character never lets that part of his identity make his choices for him.

Even more interesting, however, is the film’s treatment of Nux, who is very much a product of the hyper-masculine regime that the film vilifies. The character is introduced as being so thoroughly immersed in Immortan Joe’s patriarchal puffery that just one look from his surrogate daddy figure is enough to whip the poor kid into a suicidal frenzy. The way that a character who has drunk that much kool aid is given the narrative space to grow and evolve into someone that opposes the misogynistic world order elucidates a key part of the film’s ideology. Masculinity is only a problem when it starts acting as a repressive societal force – not when it’s a physical feature – and even those who have been brought up in the most appalling of mindsets can be turned into instruments for good. It’s these two male figures that allow the film’s agenda to remain firmly within the realms of inclusive positivity instead of tipping into the man-hating propaganda that Men’s Rights Activists would have you believe can found in the film.

On the other hand, how are the rest of the good guys represented? Overwhelmingly feminine, or at least female coded. But by and by, the film takes care to constantly make them the most competent and in-control characters in the film, approached only by the title character himself. Naturally, the apex of this is Furiosa, whom Theron plays with such a degree of ferocity and icy aptitude that she mostly (and justly) steals the film. In what’s perhaps the moment that best sums up the film’s stance on male vs. female action protagonists, Max hands her the sniper rifle after he tries twice to make a difficult shot. Furiosa, using him as an impromptu stand to better aim, makes the shot, and the two move on. If a woman is the best person to do something, the film seems to be saying, she just is, and it doesn’t even have to be a big deal.

The film’s representation of women would be considerably poorer, however, if the Imperator was the only main female character. For all of Furiosa’s positive traits, it would be too easy to argue for her being yet another female character that achieves strength by coopting stereotypically male signifiers. (i.e. the shaved head, the proficiency with firearms, the military position in a hierarchy, the war make-up, etc.) Fortunately the film finds space in its plot to feature the elderly women that aid the caravan in their path through the dessert, and the extremely feminine figures of Immortan Joe’s wives. The film is not reductive in its presentation of female characters, there’s no “one way” to be a successful female figure in the world of Fury Road; rather, we find a more kaleidoscopic view that presents various models of appearance, age, and disposition, each armed with a comparable level of agency and skill.

The introduction to the wives is a particularly interesting moment. At first glance, it’s easy for this scene, of the aforementioned scantily clad supermodels bathing in the desert with the camera lingering on their bodies, to seem like a vestigial remainder of a previous generation of action filmmaking. It’s not until the film lands on the close-up of the horrifying chastity belt that’s being removed that the scene makes more sense, and it’s not until we realize that the plot of the film is literally about these women going from being objects for the satisfaction of one man’s personal sexual pleasure to coming into their own as independent human beings that the larger context for the scene makes sense. We are forced to see them as the sex objects that they have been reduced to, then sucker-punched with the horror that’s been inflicted on them. Once again, the film builds its political case through narrative: it pushes the audience towards wanting these women to be independent of the domineering dictator that has defined their existence up to that point.

This is how Fury Road does business, and it’s the reason why the film is so subversively effective at smuggling big ideas into an action film. It knows how to animate the concepts it’s trying to expound upon by making them into characters and how to set the discourse into motion. Even the ending of the film, with Furiosa and the surviving wives taking control of the citadel after Immortan Joe’s death, seems to play almost on a meta-textual level. You could say that it stands for the way that the female characters have taken over the action film after destroying the controlling influence that kept all elements suffused in testosterone-fueled imagery. And you could also take the joyous ovation they receive as indicative of the hunger for change that a people have after having one single, all encompassing world-view of how things should be foisted upon them for a really long time. And if you did that, well… I would call that an interpretation of the film, but it’d be one that is working with the prime material that Miller and Company have laid out. Definitely not crazy talk. But ultimately that is the greatest triumph of Fury Road, it has created the space to have this discussion about femaleness, feminism, and action filmmaking, and a great case study for how these things can intersect to broaden our horizons. More films need to do that.

And more films need to feature rock band cars with flame-wielding guitarists.