The recent remake of the 1970s Death Game starring Keanu Reeves definitely pulls much of its plot and general explicitness from the original exploitation film. A nod to film history is always appreciated but comes across a bit less admirable when it pulls in modern tradition. In this sense, Knock Knock (2015) misses the ball, both as a respectable film and as a feminist statement.

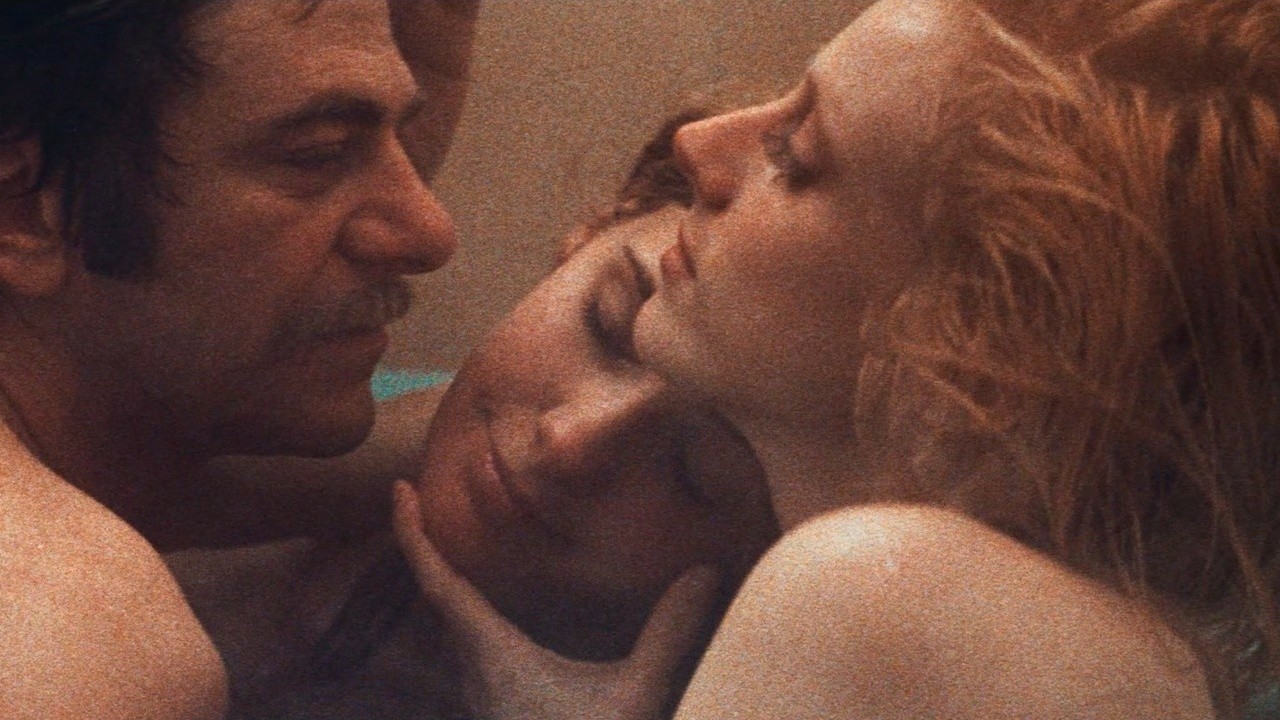

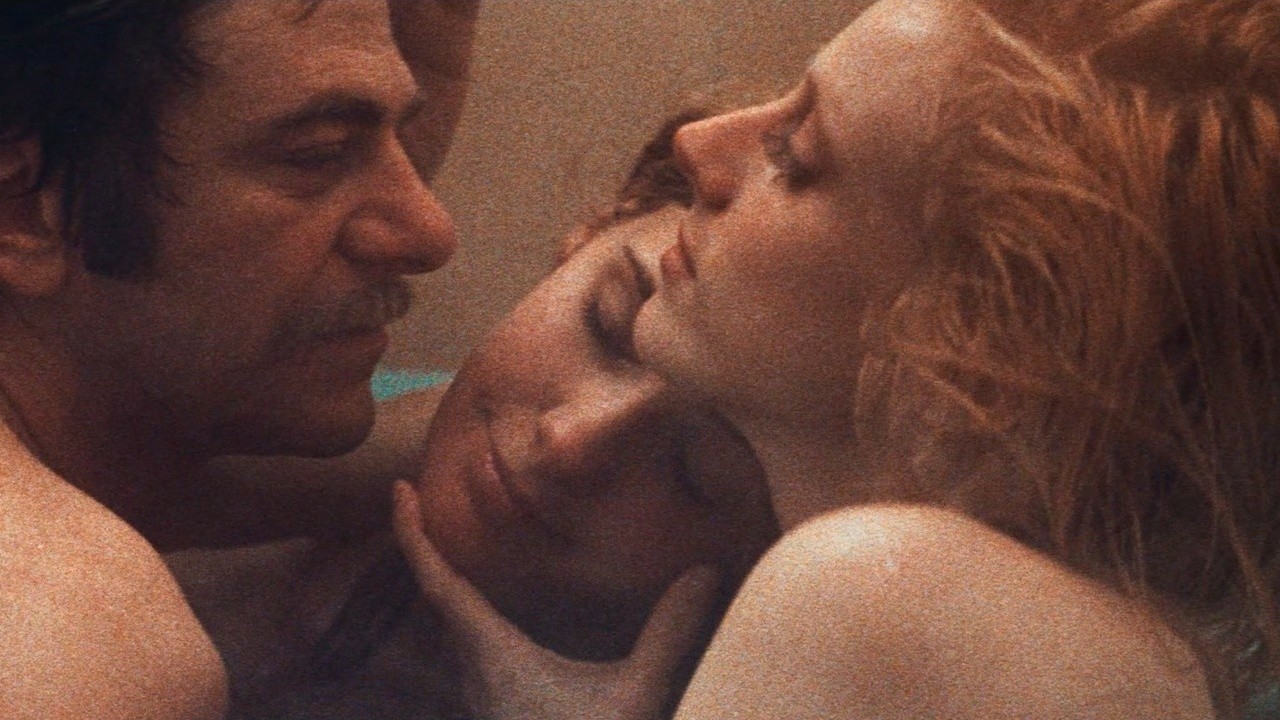

The original Death Game (1977) featured primarily the exact same plot as its renovation. A married man is left home alone for a weekend when two surprise visitors show up at his door. The two strangers, attractive young women, are quick to seduce or, more accurately, coerce the male homeowner. After a heated sexual encounter, the two refuse to leave the married man’s home, claiming to be underaged and threatening to report their affair to the police if the man tries to make them leave. After trying to drop them off at a nearby, but far enough, location the two appear back at the man’s house, sexually and physically abusing him, and holding him to a death sentence trial for his immoral deeds.

1970s exploitation films were a subculture of their own. They took the most violent, perverse, and sexual topics and subjected their viewers to them. Many texts will specifically state that this trend in films was not, in itself, a genre, but a period of time in which filmmakers were pushing the envelope and veering into the outrageous and grotesque. To many, especially those who appreciate the avant-garde, certain subcultural film movements are sacred in their original form and are not meant to be adapted into more conventional narratives. This is precisely where the weakness of Knock Knock lies; it takes a very specific, countercultural film movement and attempts to morph that into a classical Hollywood narrative. Taking 1970s exploitation narrative directly out of the context of that movement and time period, immediately throws the plot off kilter. Adding in random contemporary elements, like a 3D printer, Facebook, iPads, and Ubers kills off any non-conventional feel that this narrative might have once embodied- it instead becomes a painful amalgamation of the gruesomeness of exploitation cinema and the tackiness of poorly done modern horror.

Despite it’s ugly reference to film history, the film becomes a dangerous beacon of quasi-feminism, as it does try to tell the narrative of a revenge plot, adorned with empowered women, but ultimately fails to do so. After watching the film, with a less critical eye than a typical film buff, it would not be surprising or off base to imagine Knock Knock as a female revenge plot. But it is imperative to note that it is not! The film does nothing in it’s representation of women except for painting seductresses Belly and Genesis as power-crazed, violent sex offenders. In the original plot, the two seductress’ bizarre behavior is explained by an earlier trauma in one of the women’s lives; rape by her father. In the Keanu Reeves remake, this key explanatory piece of information is left out, leaving the audience to try to rationalize or piece together the women’s behavior through the little character development they are given. This leaves the narrative almost impossible to piece together and heavily villainizes the female antagonists, as their actions seem to unfold completely without explanation. The women just seem like deranged psychopaths, which they may as well may be, but some context for the psychopathy would have allowed their female characters more dimension, and developed them as real humans, rather than flat, villainous placeholders.

There is no feminist statement, no statement really at all, made by this film. In fact, the representation of the mangled and graphic feminism that this movie portrays is extremely damaging for the sake of gender equality. Belly and Genesis seem to have some sort of hidden feminist agenda, claiming they are punishing Reeves for his manhood alone. They claim that all of their victims succumb to their sexual advances, making him no different and, by default, equally as guilty as any man who has ever done anything bad. This is a completely backward look on what feminism and gender equality means: the feminist movement aims to achieve equality among all people, not violently destroy the lives of the male species. Attempting to guise Belly and Genesis’s characters as women who are championing for other women is harmful, especially as absolutely no context is given for their revenge plot in the first place.

Exploitation films can and should continue to be pursued in modern times, but in unique and innovative ways, as the avant-garde always tried to do in the first place. Trying to mold a 40-year-old narrative into modern production norms resulted in the Frankensteinian monster of Knock Knock that not only disappointed the name of exploitation cinema but, more consequentially, served as a completely irresponsible representation of feminism and female empowerment.