Here’s an idea: with Into the Woods, Disney may have made their darkest, most subversive, and most adult film to date.

All right, hold up, let’s get this out of the way: this article will contain some general plot discussion of the play Into the Woods, a 25-year old production of which there is an excellent recording on the iTunes store that you can go watch right now. I will be discussing general story elements that happen throughout the play and how these have been adapted into the Rob Marshall directed film that’s coming out this Christmas. We won’t be going into the nitty-gritty of anything with too much detail, not more than a thorough plot summary or particularly lengthy trailer might. If, however, you know nothing of this story’s secrets and want to keep it that way, then Happy Holidays and we’ll meet you back here on the 26th.

Into the Woods is the kind of property that somehow seems to be both a perfect fit for the Disney filmmaking conglomerate and the last property that the House of Mouse would ever want to be associated with. On one hand, the general premise of the Stephen Sondheim-composed, James Lapine-written 1987 monster Broadway mega hit seems a perfect fit for the child-friendly studio. In a Love Actually-style mash-up, the main events of the most famous entries in Grimm’s fairy tales all take place side by side, connecting and colliding over the course of three days in the woods behind a small village. Two of the stories, Cinderella and Rapunzel, have, in fact, already featured prominently in Disney productions, with Jack and the Beanstalk, Little Red Riding Hood, and an original fairy tale about a cursed baker and his wife rounding out the proceedings.

The first act of the play is a breezy, creative retelling of all these stories, with the various characters interacting with each other outside their original storylines in both obvious and deviously surprising ways. It all builds up to a grand, bombastic finale in which everyone lives happily ever after. You get a creative spin on the fairy tales that you’ve already explored, and a larger framework gives substance to the shorter stories that can’t quite sustain a feature film on their own. And all of that is propelled forward by a set of classic songs by one of the few entities in musical theater that can hold his own against the classic Menken/Ashman compositions of the early Disney Renaissance. What’s not to love?

The problem is that the play is only half over at the aforementioned “Happy Ever After” point. In the second act things get dark. Really, really dark. A series of selfish, unconscionable, or just simply shortsighted decisions that the characters made over the course of their traditional stories come back to haunt them, and once the plot steps off the rails of the well-known story everyone starts acting in a very un-Disneyfied fashion. Before the final curtains falls, the characters will go through (hold onto your hats) sex, serial adultery, child abandonment, revenge-seeking, divorce, multiple murders, moral dilemmas, metatextual fourth wall-breaking, and a soberingly stark parable about the terrifying way in which one’s words and actions can affect or destroy lives.

In other words, the first half of the play sets up the mechanics of a classical, fairy tale-inspired Disney film before the second half bares its fangs and hits the audience with everything you wouldn’t see in one of Uncle Walt’s movies.

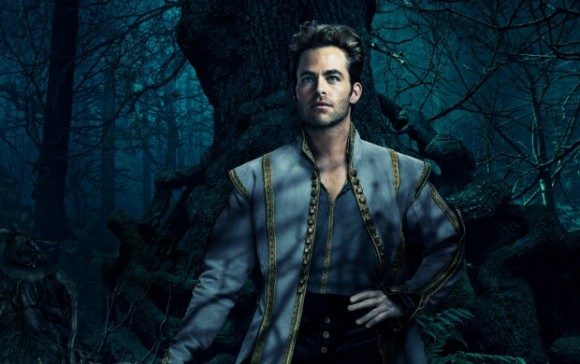

This shift in tone is the central operational conceit the play is constructed around. Much as people love to say that Into the Woods is about being careful with what you wish for, it’s actually a play about personal responsibility and perspective. It illustrates the dangers of going through life thinking of everything in sanitized, fairy-tale terms by creating a storybook world and then tearing it apart. The turns are calculated to undermine the Happily-Ever-After formula, almost like the play is saying, “Oh, that prince that wooed you into marrying him? What exactly makes you think that he’s not going to keep seducing young maidens that catch his eye? What makes you so sure that the protective parent that has sheltered you all your life don’t have a valid point or two? And, umm, that giant that you robbed, tricked, and killed? That was a person. Why is it surprising that you would be held responsible for everything you did to him?”

None of those are simple issues, and the play ends for the so-called heroes on a note of, “We’ve done a lot of bad things, and we need to try to do better,” a far cry from the jubilant cries of naïve victory that accompanied the end of their traditional stories in the first act. It’s a calculated rug-pull, one that works because the audience is so firmly planted in the fairy tale mechanics for an hour and a half before things start going ape. In other words, it’s a story that starts off as a Disney film, and then twists itself into something more complicated, something about how dangerous it is to look at life the way a Cinderella or a Tangled does.

Bernadette Peters in the Original Broadway Production of ‘Into the Woods’. The first act’s nominal villain, her centerpiece musical number in the second act is a song about all the trouble the other characters have caused by caring too much about acting or seeming “nice.”

So… how do you turn that into a film that the real Walt Disney Studios is comfortable producing? What do you do with that second layer?

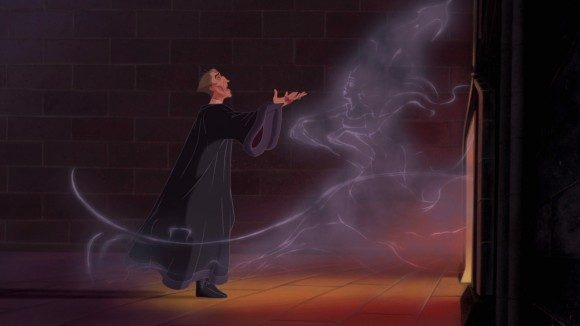

Okay, so the suggestion of this happening is not nearly as ludicrous now as it would have been twenty-five years ago. Since their Renaissance in the 90’s, Disney has stretched its storytelling muscles in surprisingly adult directions, particularly with its live-action films. Last year’s Saving Mr. Banks dealt in a fairly direct way with the consequences of alcoholism and substance abuse. This year’s Maleficent restructured a classic fairy tale Disney film around what could easily be read as an extended rape analogy. The third film in the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise opened with the execution of a young boy. Perhaps most saliently, Victor Hugo’s odyssey of social ills, abuse of religious power, and sexual obsession was adapted into an animated musical extravaganza with The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

But as surprisingly effective as the writing and the music in Hunchback might have been in smuggling through the ideas of Frollo’s dark sexual desires, the fact of the matter is that the book and the film are very different animals. The focus on the film is not on the novel’s ideological critique of a decaying society, it’s on a personal story of overcoming prejudice and asserting one’s self-worth. The film uses the novel’s admittedly dark material to propel itself in terms of plot, but it ends up with a final message that is very much in accordance with the Disney worldview. Whether or not you think that the film works as a piece of art on its own terms, and I happen to think that Disney’s Hunchback does, it’s an uphill battle to claim that it’s representative of the agendas found in the novel.

Most Sondheim fans feared that this was the fate that awaited the stage musical upon its translation onto the big screen. We’d get a version of Into the Woods, possibly even a very good version, but it would be a film that used the original as a springboard for a more conservative enterprise. These concerns were only exacerbated a few months ago when an interview with Sondheim all but confirmed a few of the story’s darker twists and numbers wouldn’t be showing up on the silver screen. All of which made sense – Disney would never make something as darkly subversive of its own formula as Into the Woods is. A property like this one would have to be approached with the same degree of moderation and compromise that saw the likes of Hunchback of Notre Dame through to completion.

But what if Disney had approached this project not with moderation, but with an utter purging of the play’s subversive nature. Could they even go as far as cutting out the entire second act and just release a straight take on the first act as the ultimate distillation of a Disney fairy tale? This is a studio that is famous, some would say infamous, for the jealousy with which it guards its carefully constructed image and sensibilities. The risk that it might make a film that actually supports the twisted view of reality that the play condemns seemed a little too real for comfort.

All of which takes me to what is perhaps the greatest surprise that I have ever had in a Disney film: when Rob Marshall’s film got to the point where things got ugly, where any self-serving Disney executive would declaw the proceedings, it… did not. The second half of Into the Woods, where choices get difficult and any sense of black and white disappears, is all there. The extremity of the play is not completely intact by any means, and things have been toned down. Various characters that die in the play are still alive at the end of the film. And the charming prince does not have sex with anyone other than his wife. But general infidelity? Yes. Child abandonment? Yes. Divorce? Yes. Death? Yes. Murder? Yes. Difficult choices, moral ambiguity, a dawning sense of responsibility to the world around you? It’s all there.

I’m not saying that the film is above reproach as a standalone work of art (look for our upcoming review of the film to get our thoughts on what works and what doesn’t), but in making this story and these choices a part of the Disney canon, Disney has made an extremely brave decision. This is a film that takes a good, hard look at the aesthetics, values, and traditions that were Mickey Mouse’s bread and butter for the vast majority of his eighty years in the movie business. It’s a sign of the studio’s increased consciousness about the messages they are sending, and hopefully of a willingness to critically examine its role as a social trendsetter. Last year’s Frozen had a revolutionary step in its third act twist about the dangers of falling in love with handsome princes. Into the Woods is far harsher and more blunt in its critiques, and as a result of that it’s an even bolder leap forward.

If you are a Disney fan and you’ve never seen the stage show, go see Into the Woods this Christmas. I cannot promise that you will enjoy it through and through, but it’s an illuminating, some might say necessary, companion to the Disney Princess line. And if you are a parent, especially one with a child around the ten-year-old range, go see this film with them. Just be conscious that the first half of the film will be talking to them while still being entertaining for you, while the second half will feel more aimed at you while still being accessible to them. It may not turn into the next Disney film that will play non-stop around the house, but it may lead to an interesting conversation about what the two of you just saw and how that interacts with other movies you’ve seen. And that, more than anything, feels like what this adaptation was made to do.