If you are a fan of science fiction films, or unique visions of the post-apocalypse, or smart action thrillers, or phenomenal ensemble cast performances, or… you know what, screw it, if you like movies and you’re anywhere near a theater that’s playing it, you owe it to yourself to go see Snowpiercer. Korean director Bong Joon-ho’s English language debut is a film that does a lot of things to set itself apart from the deluge of summer blockbusters. It’s an international production in the true sense of the words: made by a Korean filmmaker, adapted from a French graphic novel by the director and an American screenwriter, and shot in Eastern Europe. The cast dares you to find a more diverse range of actors, bringing together multiple Oscar winners, breakout stars of gonzo Korean cult films, and the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s reluctant golden boy. In a time when practically every major film is building upon the support system of preexisting franchises or sure-fire properties, Snowpiercer launches itself into unknown and untested waters with ferocious abandon.

This is just a tiny sampling of the things that make Snowpiercer one of the most memorable films released so far this year. Add to that its ingenious quasi-limited setting, masterful command of film grammar, and impeccable production design, and you start to get an idea of how much of a success the film really is. But Snowpiercer’s strengths have their roots at a more architectural level, stemming directly from the film’s robust and inventive screenplay. Bong and co-writer Kelly Masterson put together an adaptation that is brimming with three-dimensional characters, smart dialogue, unexpected moments of dark humor, and, above everything else, a clockwork structure that assembles and pays off twists and turns at such an breakneck pace that it really must be seen to be believed.

The astute among you may have noticed that I haven’t yet told you what Snowpiercer is even about. And I’m not going to. As the title might suggest, this is an article meant for those who have already experienced the uniquely invigorating insanity of Bong’s piece. In our efforts to wrest the secrets of the film’s power from it we are going to go into a lot of detail about what happens, how it happens, to whom it happens, etc. Many of you will want to discover this film’s pleasures without me priming you for them, so take this as your official spoiler warning. I realize the film is not yet available for viewing everywhere, but don’t worry, this article will be right here when you get a chance to see it.

Snowpiercer opens with Curtis (Chris “Cap’n America” Evans, hiding his musculature under yards of costuming to appear malnourished) plotting the latest in a series of doomed revolts against the totalitarian military that enforces the train’s ironclad caste system. He is backed by faithful sidekick Edgar (Jaime Bell), watched over by one-armed and one-legged mentor Gilliam (John Hurt), and assisted by an anonymous informant in the front section of the train. It’s the last of those, unknown and unseen except for the messages he smuggles in through the periodic shipment of food cubes they receive from the higher-ups (or, as the case may be, the further-fronts), that starts off the plot in earnest.

One of the first things we see in the film is Curtis and Edgar tracking down the latest note from their informant, which ends up being in the hands of a young boy named Timmy. At first glance, this just seems like a film’s regular introductory movements, familiarizing us with the characters and conditions in the back of the train and, smartly, doing so through action rather than narration or dialogue. From the vantage point of hindsight, though, we can see that the film is already starting to very carefully reveal the underlying machinery that makes Snowpiercer churn onwards.

Introducing characters in a way that generates sympathy? Check. Starting off the plot with the main characters being active protagonists? Check. Setting up the ultimate climax of the film by bringing together the elements Curtis will be faced with at the front of the train? Also check.

Bong’s film is about nothing if not forward momentum, and we are soon launched into our first major crisis point. A representative from the front of the train arrives and, after a cursory inspection, makes off with two children, young Timmy among them. When Andrew (Ewen Bremner), the father of the other child, throws a shoe at the functionary in frustrated desperation, the gloves come off. He is quickly apprehended, stripped of his clothing, and taken to an opening on the side of the train. “At this altitude,” one of the military agents says, consulting a book, “it should only take seven minutes.” It’s a small line, but it provides us with key insight into what we’re watching. This isn’t an improvised stroke of sadistic genius; it’s systematized, structured, institutional violence. They stick his arm into the freezing cold of the train exterior, wait the few minutes it takes for frostbite to set in, and amputate it by way of icepick and mallet.

Forget Chekhov’s Gun – ‘Snowpiercer’ uses this scene to set up so many developments that even old Anton would have been impressed.

It’s a harsh, brutal scene, but it’s one that does a lot of heavy lifting for Snowpiercer. It establishes the ruthless enforcement methods of the train’s hierarchy. It generates tremendous sympathy for the back-dwellers and establishes the despicable nature of Minister Mason (Tilda Swinton, in a scenery-devouring role about which not enough good things can be said) and her attendants. The lines of sympathy and allegiance are clearly drawn. It’s also effective because it grows directly out of the film’s setting – it’s not just that they brutally take away this man’s arm, it’s that they do so by using the ever-present elements of the train and the frozen exterior world. Perhaps most importantly, the scene gives us great insight into the characters of this world. Immediately after Andrew’s punishment is over, Hurt’s Gilliam demands a word with Mason. As he hobbles towards her, prosthetic leg and arm painfully visible, it’s impossible to not put two and two together and realize that Hurt has gone through what we just saw, probably as punishment for the failed revolts we’ve heard about.

This is Snowpiercer’s primary modus operandi: it establishes and develops character through concrete action and visual developments, and, refreshingly, trusts that its audience is smart enough to get the message. It would have been simple, not to mention boring, to just have Curtis and Edgar talk about all the great things that Gilliam has done for the community. Bong and Masterson instead make this point visually, linking his appearance to an action we see occur, which is in turn linked to both the setting and the main revolt plotline. Snowpiercer’s gears don’t just work to move individual plots of the film, they interlock and propel each other forward. There’s a scene later in the film where Curtis and Gilliam are talking about Curtis’s insecurities. Gilliam tells him that he’ll be a great leader and Curtis replies that he doesn’t know how the people in the back of the train will follow someone that still has both his arms. It’s all we need to understand his interior conflict.

The messages from his informant lead Curtis to the prison section of the train, where they unearth security specialist Namgoong Minsu (Bong mainstay Song Kang-ho). He doesn’t care one jot about their revolution, but agrees to help them in exchange for Kronol, industrial waste that can be consumed as a highly addictive drug. At this point we’ve already been introduced to the substance; Curtis had some of his compatriots in the back of the train collect Kronol, hoping to use the chemical’s flammable properties as weaponry in the revolt. Instead, it’s the Kronol’s properties as an addictive substance that ends up facilitating their revolution. All Namgoong cares about is the escape that the drug can give him. One piece of Kronol for every open door. As with the missing limbs, Snowpiercer has faith in its audience’s ability to keep up with its subversions of expectations.

But the film is also smart enough to always be two steps ahead of them.

Let’s dart past the bulk of the film to see how the machinery of Snowpiercer’s writing ultimately snaps into place with exacting, terrifying precision. As the rebellion fights its way to the front the body count gets higher and higher, to the point where the only three insurgents to make to the doorway leading to mysterious engine room and its enigmatic keeper, Wilford, are Curtis, Namgoong, and the latter’s teenage daughter Yona (Go Ah-sung). As the film prepares itself for the final hurrah, the motifs that it’s built up unravel.

First, there’s Namgoong, who suddenly refuses to go along with Curtis’s plan, instead suggesting that they open a heavily reinforced door that leads the exterior and abandon the train. And what does he suggest they use to get this door open? The Kronol that he’s been collecting for the entire film, pasted together to form an explosive with tremendous firepower. The earlier reversal is turned on its head: it was the substance’s incendiary capacity that made it so attractive. Namgoong’s claims of using the Kronol as a means of escape take a different, a literal, meaning as they are recontextualized. It’s a twist that reframes the characters’ actions throughout the film, but it’s one that works for two reasons. First, it doesn’t go against what has already been established about the character, just casts a different light upon it. Namgoong still doesn’t care about the revolution and just wants a way to get away from it all, it’s just through an option that we hadn’t considered. Second, the base material for it was seeded early in the film, planted and then seemingly dismissed.

Lesson the First: the best twists are born out of characters’ motivations and actions, and are an extension of their psychology rather than an upturning of it.

Curtis, of course, isn’t convinced, and shares his own personal story with Namgoong. In the early days of the train, the tail end was left to fend for itself, leading to the desperate masses resorting to cannibalism. Curtis, it seems, was a mindless brute, one who was only prevented from eating a young Edgar by Gilliam intervening, cutting off his own arm, and offering it as food instead. The earlier piece of characterization that we had so masterfully been led to conclude is upturned, and we finally learn the real dynamic that existed between Curtis, Edgar, and Gilliam.

But, wait, isn’t this just a character talking about the great things that Gilliam has done for his community, the exact thing that I praised Snowpiercer for not doing earlier? Absolutely, but the proof is in the pudding. If this had been the way that we had been introduced to the character odds are it would have come across as lazy or sloppy, but we’ve already had almost an entire movie’s runtime to form our own opinions about the man by seeing him in action. It also works because this scene is a reversal of a pattern that has been present throughout the entire film. Since the film has been so good at establishing characters through visuals and action rather than through dialogue, when it suddenly sits down for a long stretch of a character talking about his backstory we really pay attention. This key moment of context and backstory doesn’t feel hackneyed or half-baked – it lands like a nuclear bomb.

Lesson the Second: Character development doesn’t automatically have to mean a changing relationship between the characters, the evolution can be in our understanding of a complex onscreen relationship.

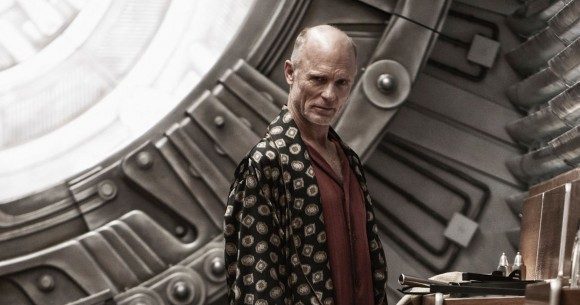

The twists and machinations of the plot are outlandish, but they don’t really feel forced because they are always rooted in the setting, the characters, or subtle connections the film drew in its early stages. This is especially apparent as Curtis gets ushered into the engine room to meet Wilford and the film descends into a flurry of revelations and reversals. In quick succession we learn that Curtis’s revolution was secretly engineered by Wilford as a means of population control, that Curtis’s informant in the first class was none other than Wilford, that the train’s overseer has been kidnapping children in order to use them as replacement engine parts, and that the population of the back of the train is largely kept around as a source of children to keep the train running with. Timmy, long absent from the screen, is revealed to be trapped within the train’s perpetual motion engine, doomed to spend the rest of his life cranking gears. It’s a lot to take in, but the film’s elegant design helps to ease us through the sharp turns. It takes a moment to remember the earlier scene with Curtis trying to get a message from his informant (now revealed to be Wilford) from Timmy. The film opens by drawing together the three characters that will be present at its climax. Just like Wilford has a deliberate, exacting plan for the train, Bong and Masterson laid out the foundation for their plan since the start of the film.

Lesson the Third: Any development or outcome can be made to feel organic and appropriate if the proper groundwork is laid for it. The real trick is doing so without calling attention to the organizing presence that’s setting up the pieces.

The threads in Snowpiercer converge in such a carefully arranged way that the story’s ultimate conclusion feels organic and fitting. When Curtis sacrifices his arm to jam the mechanical apparatus that is keeping Timmy trapped within the engine, it comes with this sense of, “Of course. How else could this character’s arc have ended?” Like all good conclusions, it’s feels both unexpected and inescapable. The film’s script is a masterclass in efficient, economical storytelling, with characters’ actions having long-term impact, each individual piece being connected to multiple other ones, and every point of possible ambiguity or multiple meaning being milked for all its worth. Every endgame twist has its foundation meticulously laid out, with each initial thread complicated, developed, or inverted.

There is a lot more to appreciate and absorb from this film’s excellent screenwriting practices, but this is a good primer on this script’s fastidiousness. In a summer that has already seen a few brave and unusual science fiction films, Snowpiercer still feels like a remarkable breath of fresh air, but for all of its innovations and its peculiarities it is built on bedrock of efficient storytelling practices and an ironclad structural foundation.