Discussing comedy – specifically the mechanics of how comedy works – is one of the trickiest tasks that a commentator can set for him or herself. Humor is often instinctual and involuntary, working around the higher levels of intellectual engagement rather than through them. Trying to break humor’s inner workings into its mechanics is too often an errand doomed to failure. Even in the best of cases the results can be overly clinical – a cold appreciation of a construction replacing the genuine laughter. (Put another way: nothing kills a joke faster than explaining why it’s funny.) In the worst cases, the discussion can boil down to nothing more than a referential list of things that are allegedly funny without any insight into why they are funny. Combine all of this with the fact that comedy more than any other narrative form is inevitably influenced by the currents of subjectivity and the result is a form that is massively popular but insidiously difficult to discuss in a meaningful way.

By and by, a lot of the discussion on comedy centers on the odd paradox that lies at its heart: the need for a visceral sense of dangerous stakes and for narrative distance to cushion the audience from actively empathizing with the subject. Whereas a horror film (among others) will work to erase our awareness of the film’s artificiality in order to get us viscerally worried about what we’re seeing, a comedy film needs to constantly remind us of its status as an unreal creation. It’s that sense of distance from the dangers that we’re seeing that lets us laugh at them. Or, as Mel Brooks puts it, “Tragedy is when I cut my finger. Comedy is when you fall into an open sewer and die.” It’s the reason so many of the best comedy films combine serious, sensitive, or controversial material (violence, sex, politics, humiliation, etc.) with devices that highlight the medium’s artificiality (animation, parodies of or references to other films, and basically everything Edgar Wright does).

More often than not, when a comedy film doesn’t work it’s because the walker in this delicate tightrope act has fallen. If there’s not enough of a sense of a danger in the comedy, or if the filmmakers build in too much of a sense of distance into the proceedings, the results can be so insipid as to have no real urgency to drive the plot or the comedy. If, on the other hand, there’s not enough distance built between the audience and the material, the alleged jokes can come across an offensive, upsetting, or abusive upon impact. As one side of the equation gets more weight, the other one has to be escalated accordingly. (There’s a thoughtfully considered reason why South Park is so crude in both the material it tackles and the quality of its animation.) It’s a difficult machine to calibrate with success, but every so often a film pulls off this feat with such effortless aplomb, such precision, that it illustrates why so many artists strive for this ideal.

Friends, we have a new film of this caliber in front of us. For all of you comedy aficionados that have been starving your way through the Unfinished Businesses and Get Hards of the world, there’s a new shining star to look for. That film is What We Do in the Shadows.

Shadows is the brainchild of New Zealand filmmaking duo Taika Watiti and Jemaine Clement, (of Flight of the Conchords fame) who wrote, directed, and starred in the film. After a successful run in its native New Zealand and Australia, the film opened in a limited (as in two theaters) run in the States thanks to a Kickstarter campaign. In the film, a brave documentary crew, armed with crucifixes and other precautionary measures, sets out to document the night-to-night activities of four vampires that live together in suburban Wellington. Viago (played by Watiti) is fastidious 18th Century dandy, ever awkwardly concerned with cleanliness and propriety. Vladislav (Clement) is a washed up rockstar of the vampiric world, clearly modeled on the historical figure that provided the basis for Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Deacon (Jonathan Brugh) is the bratty youngster of the group, (only 183 years old!) a directionless slacker who cares too much about his personal sense of style. And finally there’s Petyr, (Ben Fransham) an 8,000-year old monstrosity that lives in the crypt-like basement and is a dead ringer for Max Schreck’s Nosferatu. In anticipation of a major supernatural event, the (fictional) New Zealand Board of Documentary has commissioned an expose on its vampire minority, so the camera crew follows these four undead individuals for months, recording every part of their daily routine.

Now, a quick disclaimer before we proceed. Remember when I mentioned subjectivity a couple of paragraphs ago? Well, by my subjective estimation, What We Do in the Shadows is one of the most successful films I’ve seen this year, and one of the most effective comedies I’ve discovered in a long time. Other perspectives on the film, including our own review of the film, have been positive, but perhaps not as ecstatic. For this piece, I’ll be doing my best to temper these opinions with a bit of sober analysis and focus on analyzing the concrete, structural decisions the filmmakers made when they put the film together… but just keep that grain of salt in the back of your mind. All right, let’s get to it.

The decision to make a comedy about this particular subject matter is definitely a bold choice. There’s no way around the fact that this is a film about a group of cold-blooded murderers. There might have been a way for the filmmakers to make a movie about the accouterments of the vampire mythology without confronting the bloody elements of the creatures’ nature, but that’s not this film. All told, the protagonists take the lives of at least a dozen people on screen, often in very graphic and gruesome ways. No one ever offers up any suggestion of remorse or a guilty conscience – violence is just a part of these guys’ existence and, therefore, the order of the night. How do you make comedy out of that? How can you effectively disarm something that is as inherently evil and violent as this film’s subjects?

Step one: get the most incompetent vampires in the history of film. It’s hard to feel very threatened by the things that go bump in the night when every part of the process is a gargantuan struggle for them. Viago, Vladislav, and Deacon are repeatedly shown at their worst, struggling with even the most the most basic of tasks. The film asserts this right from the get go: its first image is an alarm clock going off at 6:00 PM, waking up Viago. He opens the lid from his coffin, and rises up from his slumber, Dracula-style. Halfway through the process, however, he stops, gasping for air. “It’s okay,” he tells the camera, forcing a smile, “I’ve got this.” Finally, through tremendous effort, he finishes pulling himself upright. The film opens on an image that is iconic in the annals of film vampires, but it wastes no time in turning it upside down, showing it as a haltingly awkward process. It’s the entire film in a nutshell, and it happens in the first sixty seconds.

Step two: turn the vampires’ powers against them. It’s not just that the lead trio of the film struggles every step of the way – the film also finds ways to turn every part of their vampirism into an obstacle for them to overcome. Take for instance, the fact that vampires cast no reflection. Most of the time, films would play this mythological tidbit for creepiness, using it to reveal a character’s evil nature at a dramatic moment. Shadows instead asks the much more humdrum questions: how do you get dressed if you can’t know what you look like? A chunk of the film is spent tackling this problem, with the characters trying various creative ways around the stylistic roadblock. As soon as they make it out of the house, they run into another problem: vampires can’t enter building unless they are explicitly invited into them. It’s an existential rule that the film enforces with maximum ruthlessness, so the characters end up wandering through the streets of Wellington for hours, unable to enter any of the trendy clubs or bars. Dracula or Edward Cullen these guys clearly ain’t.

One of the most chilling aspects of a vampire’s powers is its ability to turn its victims into other vampires. As soon as the Transylvanian Count begins killing, the clock starts ticking down to the point when there’s a full-blown vampiric infestation to content with. In this film, this gets turned on its head when Nick, a human the protagonists intended to have for dinner, accidentally gets added into the ranks of the undead. Nobody wanted him to become a vampire, but now that he’s been turned they’re stuck with him. (Possibly for all of eternity) A good deal of the film revolves around the Viago, Vladislav, and Deacon’s inability to stand the new addition to their family and the problems caused by Nick’s blabbing about his new status as a creature of the night to anyone willing to listen. Everything that usually gives vampires their terror and their mystique is here retrofitted into a source of childishness and annoyance.

Step three: always have the conflicts revolve around the mundane, never around the supernatural. What We Do in the Shadows is as much a film about the difficulties of living in a flat with three other guys as it is about vampires, and the filmmakers are smart enough to let this dimension be the one that drives most of the battles in the film. As soon as the roommates are introduced, the first thing that happens is a house meeting. Are they going to discuss their nefarious plans for the evening? Or plan some new way to corrupt the innocent souls around them? No, they’re going to discuss the fact that Deacon is way behind on his chores, and really needs to get off his butt and do some dishes. The ensuing argument is much more energetic and vitriolic than anything the vampires discuss about their fiendish habits.

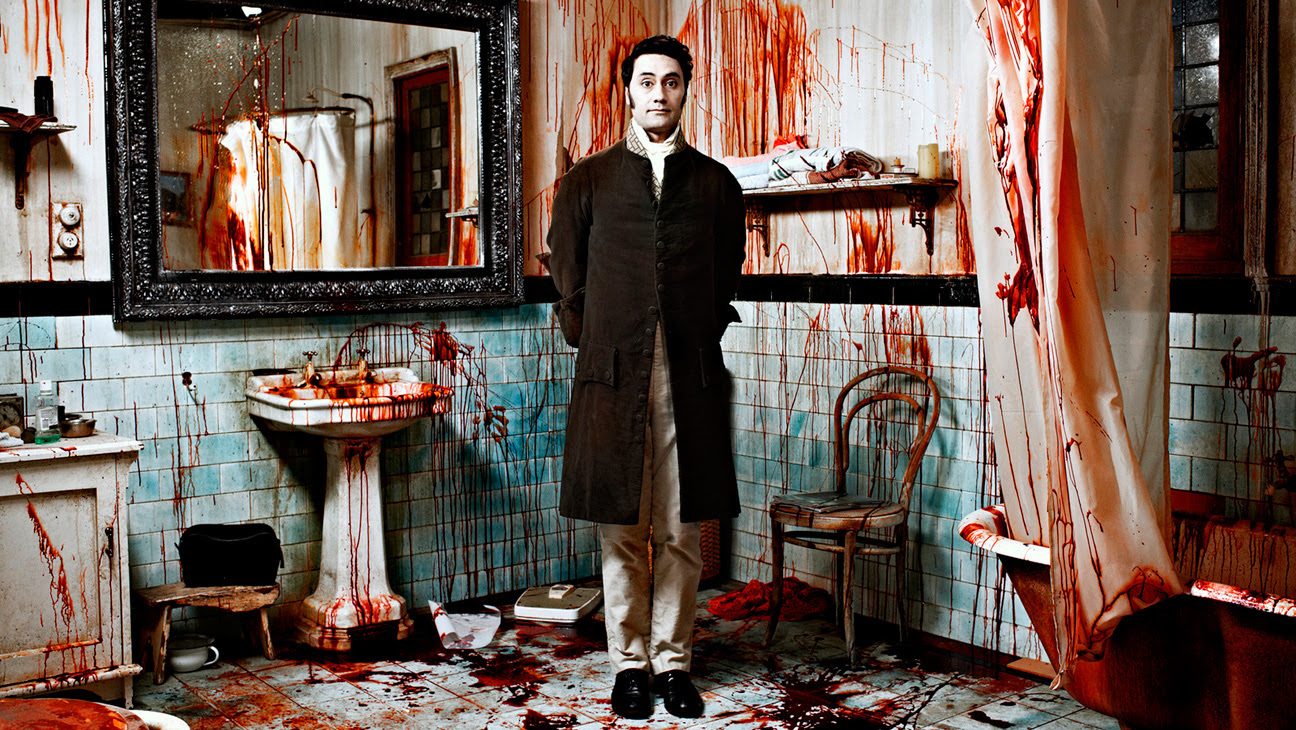

Even when the film does touch upon the vampires’ murderous nature, it’s always framed in a way that aims back down towards the mundane reality they live in. Later in the house meeting, Viago raises concerns with the way his roommates have been killing people in the living room. Not because it’s wrong, mind you, but because it’s been getting blood all over his antique furniture. Later in the film we see him laying down plastic wrapping and newspapers all over the furniture while his next victim watches helplessly.

This is the key to What We Do in the Shadows’s success: the ways it finds to disarm the dangers inherent to its subject matter. It’s a film that smashes together the unbelievably dark and the unbearably mundane, but switches around its priorities in terms of treatment. Killing people is seen as such an offhanded, such a routine, activity, that there’s no real desire in the documentary crew to explore its implications. But getting your roommate to do the dishes? Or finding the right attire to wear to club? Or getting rid of that not-quite-friend that keeps hanging around your house? There’s a challenge for you. Nevermind the supernatural, the film seems to say, it’s the mundane that you should be worried about!

What We Do in the Shadows is not just a parody of vampire films, at least not in the way that films like Vampires Suck or Dark Shadows are. That would be too simple a reduction of what’s going on here, and the humor in the film isn’t simply coming from references to recognizable tropes or situations. It’s funny because the filmmakers have taken a good, long, honest look at the practical realities that would come with being a vampire. The more time you spend with something, the more you get to know it, the less scary it becomes. What We Do in the Shadows dives into the darkness, and finds dozens of creative ways to immerse the audience in the tactile details of the living dead. It’s perhaps not the most innovative of inversions, but they have carried it off with pitch-perfect balance and, in doing so, have defanged the stuff of nightmares.