The great underlying joke of The King of Comedy is that it’s a film about people who are desperate to be famous – people who would do anything for their fifteen minutes in the limelight – made by people who had just achieved fame and success beyond their wildest dreams and didn’t seem sure what to do with it. It’s a tension that lives at the very heart of the film, and it extends outwards to all of its aspects. The King of Comedy is built on contradictions and subversions, and it’s designed to exist in almost direct opposition of everything the director had made up to that point. The result is one of Martin Scorsese’s most unsettling and difficult films – but also, and perhaps because of those things, one of his most rewarding and most representative of his concerns as an artist.

The King of Comedy is the story of Rupert Pupkin, a schlubby aspiring comic and fame seeker in New York City played by Robert DeNiro. He is ambitious and hard-working, but, alas, not particularly funny or talented. In a stunning display of wide-eyed oblivion, or perhaps desperate, willful denial, he soldiers on in his pursuit of a career as a funnyman. He’s convinced that his big break will come about by getting featured on The Jerry Langford Show (a satirical stand-in for The Tonight Show). Ever a master of human psychology, Rupert decides that his ticket to fame is to force his way into Langford’s (Jerry Lewis) life and become friends with the TV personality. But when this cunning plan inevitably falls through, Rupert hatches a darker scheme: kidnap Langford and, as a ransom, demand that he be allowed to do the opening monologue on that night’s episode of The Jerry Langford Show.

It’s hard to imagine such a thing as a Filmmaker’s B-Side for someone like Martin Scorsese. Over the past three decades, he’s emerged as such a versatile and flexible filmmaker that it’s a bit hard to conceive of there being something that’s beyond the grasp of his toolbox. Politically charged biopic of a modern religious leader? No problem. Restrained, conversational documentary about a larger-than-life personality? He’s got you covered. Adventurous children’s film? Make that “Academy Award-winning adventurous children’s film,” thank you very much. But the landscape was much more limited back in 1983, when King of Comedy was made. Scorsese had roared unto the scene with Mean Streets and Taxi Driver, and had just poured all of his personal and artistic energies (“kamikaze filmmaking,” he called it) into the hurricane of Raging Bull. His films were unified by a preoccupation with male self-destructiveness, psychotic obsession, and overriding violence. Even a detour like 1977’s New York, New York, nominally a throwback to the Golden Era musicals of MGM, plays more like an emotionally unstable dissertation about how war and modern horrors have inflicted too much upon us for those kinds of carefree stories to really reach us. Scorsese’s star had reached an early peak, but his filmography was much more rigidly contained than the one we currently know. A small, neurotic show-business drama… comedy… drama (more on that in a second) seemed more in the wheelhouse of Woody Allen than Martin Scorsese.

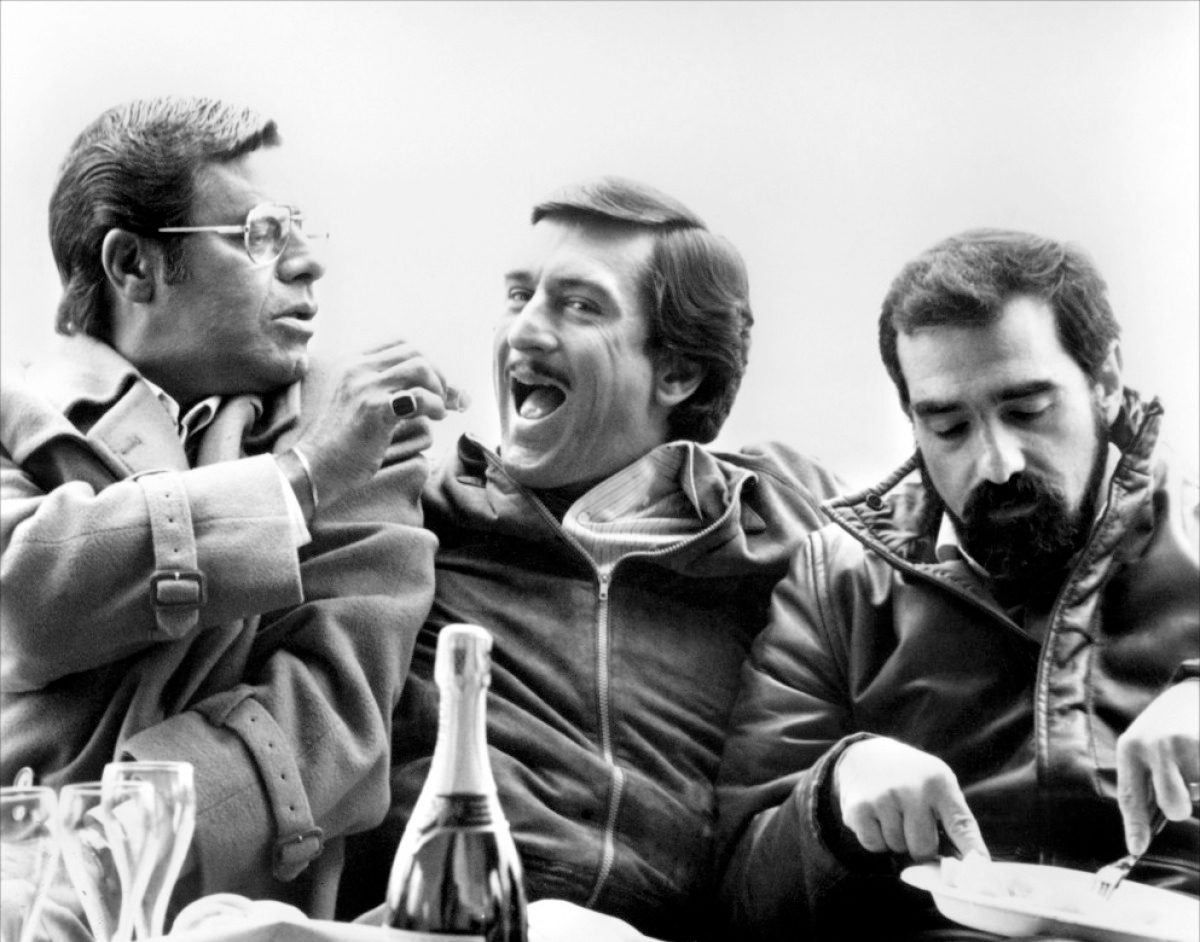

Part of that definitely comes from his continued work with his volcanic leading man. The King of Comedy was the fifth collaboration between Scorsese and Robert DeNiro. The latter had just culminated a decade of street-tough and dangerously unhinged roles with his take-no-prisoners portrayal of Jake LaMotta and its accompanying Best Leading Actor Oscar. If the choice of subject matter for the film seemed like a weird turn for Scorsese, the decision to cast DeNiro in the role of Rupert Pupkin must have seemed like a bout of madness. DeNiro’s star persona was closely tied to the lines of stereotypical masculinity and violent forward momentum. The lead in The King of Comedy is defined, above everything else, by how pathetic he is. His stature seems to adjust throughout the movie so that everyone is a good foot taller than he is. His bad haircut and overpowering moustache are only overshadowed by the fact that he lives with his mother. He looks like the kind of man that has gotten beaten up for his lunch money every day without fail for the past 35 years.

But even beyond these superficial left turns, there’s something about The King of Comedy that feels oddly disjointed from the rest of Scorsese’s early oeuvre. Scorsese had made a name for himself on a few major stylistic tricks, perhaps most saliently his moving camera. Just a few minutes into Taxi Driver are enough to feel the way the camera roves through the streets of New York, not so much following the characters as stalking them. His personal brand of expressionistic filmmaking really exploded in Raging Bull, a film that used slow-motion, lens distortions, optical flashes, color oversaturation, high contrast black and white, explosive montage editing, and elaborate camera choreographies to map out the landscape of a man’s fragile emotional psyche. So what does he do when he comes to The King of Comedy? He locks his camera down, keeping it perfectly, some would say claustrophobically, still for long periods of time. Instead of his usual kineticism, the film is pervaded by a sense of static observation. If Raging Bull got to audiences by dragging them into the boxing ring, The King of Comedy is almost as abrasive in its refusal to let viewers do anything but watch the events unfolding in front of them.

So, just to recap: the subject matter seems like a bit of a stretch for this filmmaking team, DeNiro’s gone from unstoppable force of nature to impotent fanboy dork, and Mr. Cinematic Style is toeing the line between “restrained” and “annoyingly terse.” Are there any other curveballs that this film’s got to throw at the audience?

Well… just one. Namely, the fact that no one seems exactly sure about whether this film’s a comedy or not. It’s a tricky one. Seen on a superficial level, the film seems to relish playing up scenes of extreme awkwardness or social tension, a school of comedy that has been developed in recent years by the likes of Ricky Gervais. But whether these scenes were meant to make the audience laugh uncomfortably or just plain make them uncomfortable seems to still be up in the air. While speaking at a screening of the film at the Tribeca Film Festival, DeNiro and Scorsese were asked about the experience of making a comedy. “I don’t know whether it’s a comedy or what,” replied DeNiro.

Needless to say, audiences at the time weren’t sure whether they wanted to see The King of Comedy (or what), and the film was a non-starter at the box office. It’s debatable whether any movie could have lived up to the expectations that followed a film like Raging Bull, but The King of Comedy was definitely not the film to appease fans looking for the second coming of Jake LaMotta. Roger Ebert, in a review that epitomizes the diplomatic approach of, “I admire this but I don’t like it,” writes how, “I walked out of that first screening filled with dislike for the movie. Dislike, but not disinterest. Memories of “The King of Comedy” kept gnawing at me, and when people asked me what I thought about it, I said I wasn’t sure.” Entertainment Tonight were less acquiescing, and happily branded it the “Flop of the Year.”

Still, over the years, The King of Comedy has acquired a healthy following, and quite a bit of respect amongst the film intelligentsia. It may simply be a matter of gaining insight into how adroit a director Scorsese can be, and how tricky. Approached with the hindsight appreciation of the filmmaker’s versatility, The King of Comedy can emerge as a brilliant exploration of fame and celebrity. Perhaps the ultimate key to understanding the film is that it’s a piece about comedy more than it’s an actual comedy. Its concerns are with depicting the hardship, pains, and difficulties that go into making people laugh. Its aim is to depict the backbreaking labor and endless toil that go into the process without ever letting you focus on the results.

Seen through that lens, The King of Comedy’s odd design choices make a lot more sense. The film is limiting and claustrophobic by design, imitating the state in which the characters live. Rupert Pupkin is a man that knows no release, just the relentless will to keep powering forward, and so the film doesn’t allow you to do anything other than that. Likewise, the casting of DeNiro emerges as an inspired choice. In many ways, Rupert is cut from the same delusional loner cloth as Travis Bickle, but with one major switch flipped: the violence in the character is aimed inwards rather than outward. Whereas as Travis exploded at regular intervals throughout Taxi Driver, Rupert coils further and further with each passing moment of the film, growing tenser, more erratic, more nervous, more neurotic, and with his protective, rehearsed smile growing wider and more panicked.

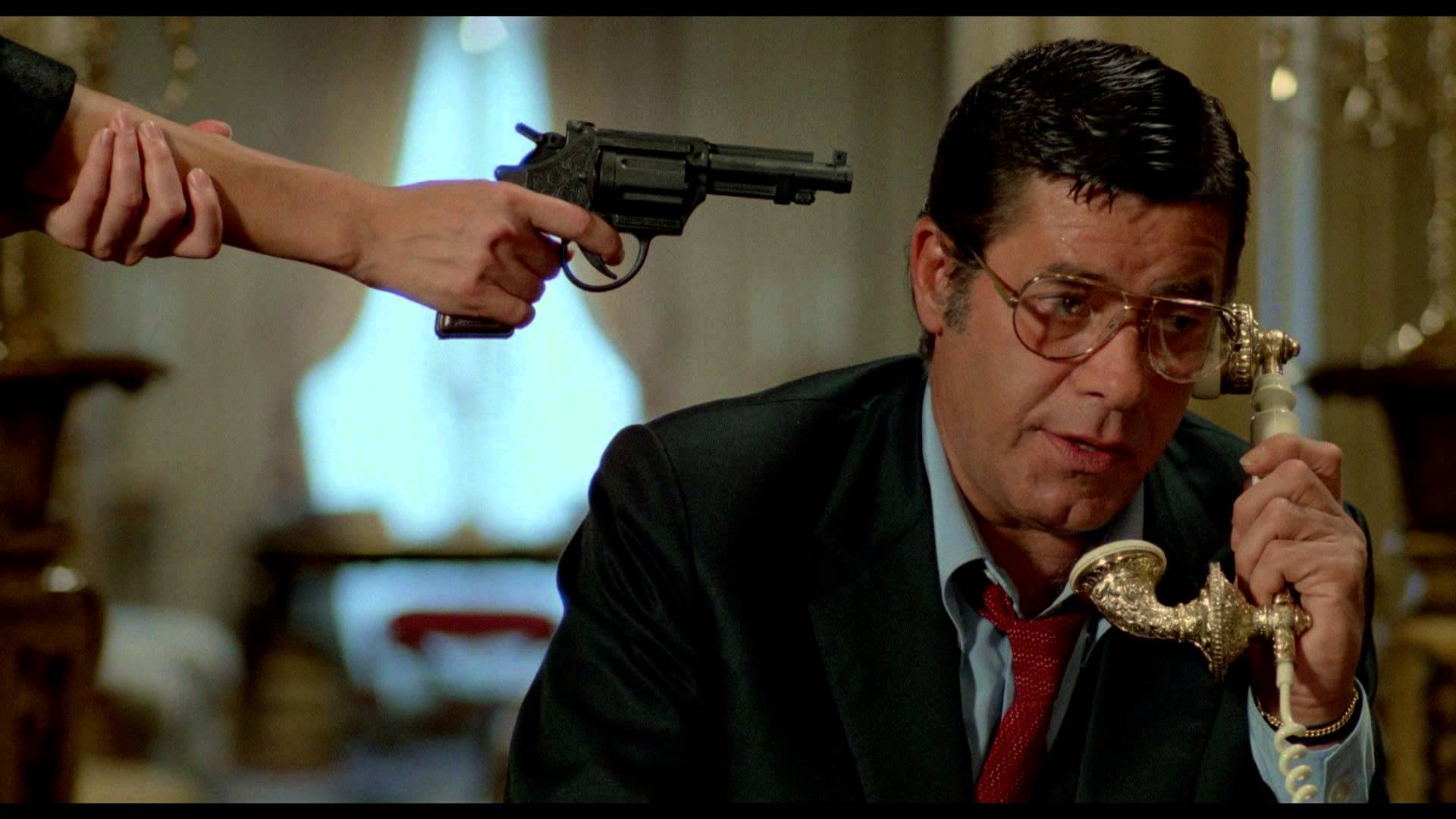

The film’s greatest asset, however, may be Jerry Lewis as Jerry Langford, the comedian god that Rupert aspires to befriend, equal, and, perhaps eventually supplant. It’s easy to see Lewis as simply playing a pitch-perfect satire of Johnny Carson, and he fulfills that role perfectly within the film, but the personal baggage that he brings into the film as a performer is invaluable. Lewis was famous as the star of comedic films like The Nutty Professor, but he had also gained notoriety for the gap between his onscreen persona and his offscreen reality. The real Lewis was known to be surprisingly acerbic and mean, a stark contrast to the joyous persona that he carefully cultivated onscreen. The King of Comedy plays him pretty much as an extension of himself – a talented, charming star that Rupert can idolize… as long as he does it from a distance. Once he gets up close and gets to spend any amount of time with Langford, he finds a man who is rude, impatient, and much more contemptuous than anyone else in the film. The message seems to be that show business success will not solve Rupert’s life – Jerry seems as broken as he is, if not more.

All of these elements come together to form The King of Comedy, an awkward, difficult, claustrophobic, and discomforting two hours of fame obsession, celebrity chasing, idol stalking, and desperate, misguided efforts to solve something inside the main characters that may just be beyond saving. And it’s in that final note that King of Comedy suddenly doesn’t seem all that dissimilar to films like Taxi Driver or Raging Bull. It’s not a film that Scorsese and DeNiro could have made any earlier in their careers, but it’s as eloquent about their concerns as the other ones. It’s a film that recognizes the violence inherent in wanting something you can never have as well as the bitter disappointment of not being satisfied when you get everything you ever wanted, and honestly not knowing which one is worse.