When you see enough films by a certain director, you begin to notice certain recurring trends or obsessions that crop up throughout their films. It’s not necessarily that the filmmaker keeps making films about the same subject matter or character type, but rather that specific elements seem to be at the forefront of all their work. Almost any Howard Hawks film from the ’40s or ’50s, for example, revolved around close-knit groups moving and talking at tremendous speeds. John Ford’s films constantly return to the power of storytelling, even when they’re not dealing with the mythological poetry of the Old West. Vincente Minnelli articulated over and over again the power that aesthetics have to save lives – or to destroy them. When you get exposed to enough of a person’s work, you begin to notice the particular filters that inform the way they put films together.

For John Frankenheimer, that filter seems to be the point of intersection between traditional, red-blooded Americana and crippling paranoia. Probably his most famous film is still 1962’s The Manchurian Candidate. That film, about an American POW who is brainwashed by Communists into becoming an assassin sleeper agent, tapped into the zeitgeist of American Cold War politics with the force of a meteor impact. His follow-up film, 1964’s Seven Days in May was even more savage – the plot followed a group of politicians in their attempt to take over the United States’ government and stop the approval of a disarmament treaty. The films’ scenarios are different, but it’s easy to see the commonalities that link them. The pleasure (or duty?) that Frankenheimer took in confronting the red-white-and-blue ideals of how the American government and military should behave is tangible.

But it’s not until 1966’s Seconds that Frankenheimer took an enormous step backwards and tackled a radically different subject matter. And it’s this film, the one that bombed at the box office and was for a long time mostly forgotten, that is perhaps most eloquent about what the director’s overriding obsessions really were.

Seconds follows Arthur Hamilton (played by John Randolph), an aging banker who’s stuck in a dead-end life. He’s reached middle age with a cushy bank job he couldn’t care less about, a lovely family that he’s utterly disinterested in, and a beautiful home filled with things that no longer hold any meaning to him. He’s lost all sense of purpose and passion, but he’s soon given a chance to reclaim them. Through an old friend, he’s put in touch with a shadowy company that offers a very unique service: for a hefty sum of money they’ll fake Hamilton’s death, give him extensive facial reconstruction surgery, and set him up with a new life.

After some hemming and hawing, our reluctant hero signs the contract, and he’s soon whisked away to be remade from the ground up. Boring bank executive Arthur Hamilton is reshaped into scintillating painter Tony Wilson (now played by Rock Hudson at his most smoldering) and is set up with a whiz-bang home in Malibu. And for a time things are great: the company has given him everything from the credentials to the art work to pull off his new identity, Arthur/Tony has a devoted manservant to tend to his every needs, and he even seems to be hitting it off with his beautiful hippie neighbor Nora (Salome Jens).

Soon, however, our hero begins to suspect that not all is well in this new paradise. One by one, signs begin to crop up that the company that gave him his new identity may be controlling various elements of his new life, and that any attempt to deviate from the very specific paradisiac parameters they’ve set up for him might have dire consequences. Have they given him a second chance to make something of his life? Or has he actually been turned into even more of a pawn – even more of a slave – than he ever was before he struck his deal with the devil?

Seconds is a film that is thoroughly steeped in the cultural milieu of the 1960s. If Frankenheimer’s other films seemed to tap into the various tensions that were in the air during those years, this one feels like it’s explicitly saying something about the decade as a whole. Watching it in 2015, it’s hard not to see parallels between this film and AMC’s juggernaut period piece Mad Men. Both Don Draper and Arthur/Tony, are disenfranchised children of the 1950s. They’re both part of a generation that was brought up on the capitalist, industrialist, and materialist principles that were suddenly rendered obsolete by the social upheavals of the 60’s; they’re the men who bought wholesale into the American ideals of the house with the white picket fence and then saw that vision crash around them. Arthur/Tony worked diligently for everything that the American Dream promised, and he got it. It’s only the accompanying sense of satisfaction that got lost in the mail.

Likewise, both protagonists try to jump the counterculture movement that is on the rise around them. Both take younger, revolutionary women as lovers and try to pass themselves off as belonging to the liberated social class that flocks around their girlfriends. About halfway through Seconds, Wilson asks Nora if he can tag along to a party she’s attending. “It’s going to be very wild,” she warns him, and she’s not kidding. The film immediately cuts to woodland bacchanal, with naked hippies running around and stomping grapes to make wine. Wilson spends all of the proceedings shifting uncomfortably, protesting as the drunken masses tear his clothes off and pour alcohol on him. The shadowy company was able to give him a second shot at youth, but they didn’t do away with the programming that’s engrained in him. Like Don Draper, he is caught in the cultural crossroads of the ’60s: he’s recognizing the hollow existence that lies at the end of his generation’s version of America, but that does not mean he’s culturally equipped to embrace the values of its successor.

The main operative difference between the film and the TV series, however, is the way that each approaches its thematic material. Whereas Mad Men hits the brakes and immerses the viewers in a meandering, slowly simmering, almost Antonioni-esque meditation on broken men and women trying to find some meaning in their lives, Seconds builds a tense, paranoid thriller around its quiet drama of identity. That’s the key to the film’s insidious power: it’s trying to make a very cynical statement about the way that the ’60s cultural shifts were failing to deliver on their promise of genuine and lasting change, but rather than just talk about it, the filmmakers dramatize this conflict. They create a story about a man who thinks he’s buying his way to freedom, but comes to realize that he’s actually been placed in a prison that’s all the more inescapable for having invisible walls. It’s the everyman version of Patrick McGoohan’s The Prisoner arrived one year early, or “Meet the new boss, same as the old boss,” in film form.

Consider, for example, a scene about halfway through Seconds. Arthur/Tony, starting to become slightly disenfranchised with the paradise routine that he’s been dropped into, is strong-armed by his manservant into giving a cocktail party for his neighbors. Frustrated and exasperated, he drinks with reckless abandon, becoming progressively more abrasive and boorish as the night progresses and he begins to question the point of it all. It’s a scene that we’ve seen plenty of other directors tackle in other films, and we know how it’s going to go: the feeble attempts of the party guests to laugh off their host’s rapidly deteriorating behavior, the escalating sense of awkwardness, all building up to some crushing moment of public humiliation.

And indeed, the scene starts off that way… and suddenly makes a sharp left turn. At some point in the proceedings something changes in the partygoers. The room gets very quiet, all the men and women start staring at Arthur/Tony, and the look in their eyes isn’t one of gawkiness or social outrage: it’s anger, the kind of quiet fury that an actor would give a colleague who is suddenly going massively off-script, or that a spy would give to a supposed ally about to blow their cover. There’s no discreet moment when things turn, Arthur/Tony and the audience just kind of look up from his drunken ramblings to find a much heavier-than-expected atmosphere looking back at them. They both think something has gone horribly wrong. And a moment later you think that maybe something has been horribly wrong from the start, and Frankenheimer has you were he wants you.

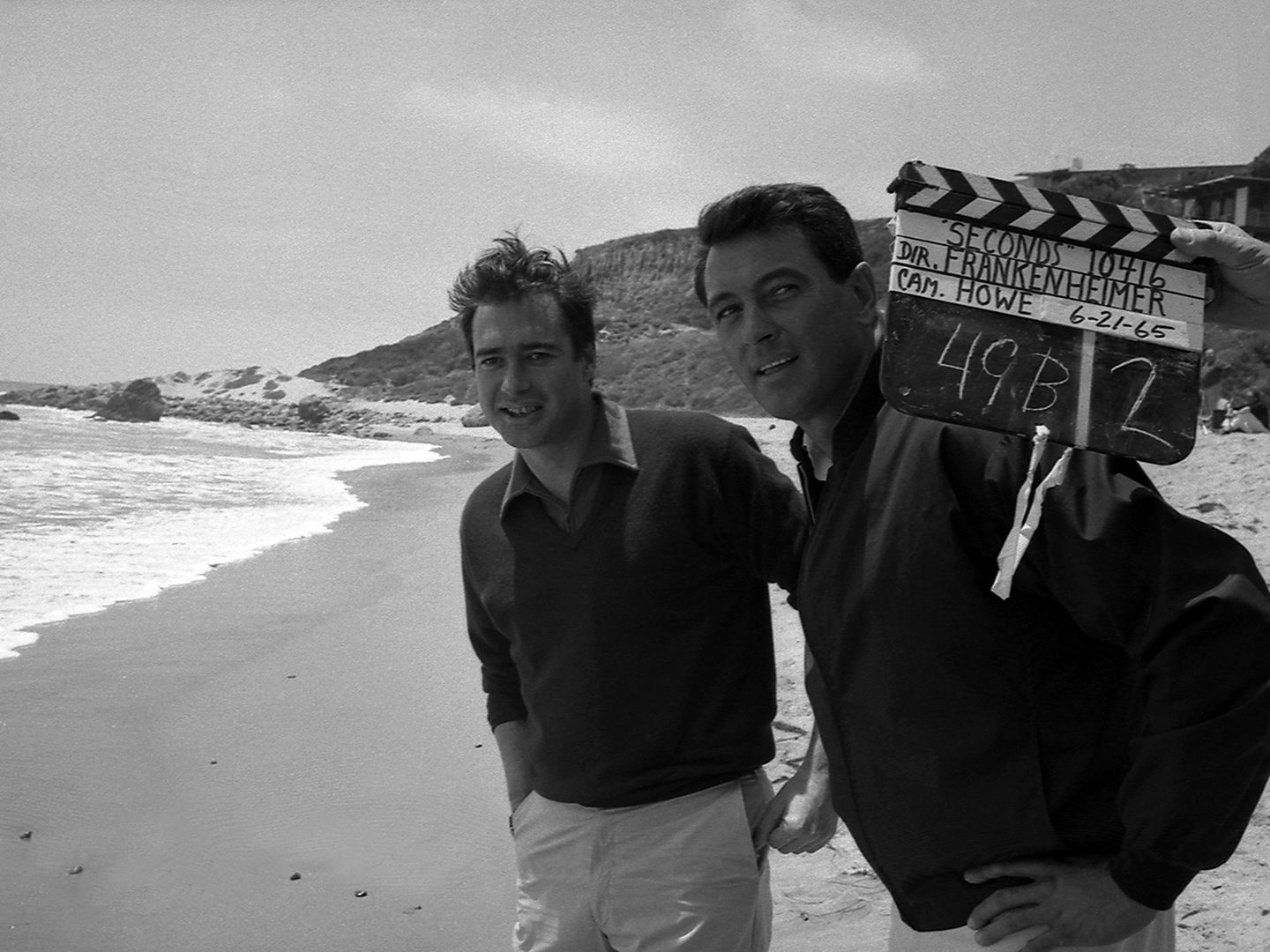

The director had two invaluable allies in his mission for this film. The first was legendary director of photography James Wong Howe, who co-designed the look of the film with Frankenheimer. Howe was one of the most prolific and accomplished cinematographers of the era, renowned for his beautiful black and white compositions and his masterful command of darkness. Seconds posed a unique challenge: the need to impose a sense of dread and uneasiness over settings and situations that, for the most part, could have come out of Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous. Howe’s solution was to use his camera aggressively, constantly framing the actors from uncomfortably close distances or using extensive distortions to twist the world into uncomfortable dimensions. His secret weapon, reserved for the most extreme of Seconds’s scenes, was a fisheye lens that completely warped the world, giving a nightmare geometry to the actions on the screen. The film’s visual register feels very close to what Orson Welles did in his film adaptation of Kafka’s The Trial, and that film was working with the stylized setting of a hellish bureaucracy state. Perhaps that’s the highest compliment one can pay to Howe’s work in this film: he’s able to make Malibu look like something out of Kafka.

Yes, this is the way it’s supposed to look. Do not adjust your set. Do, however, fasten your seat belt.

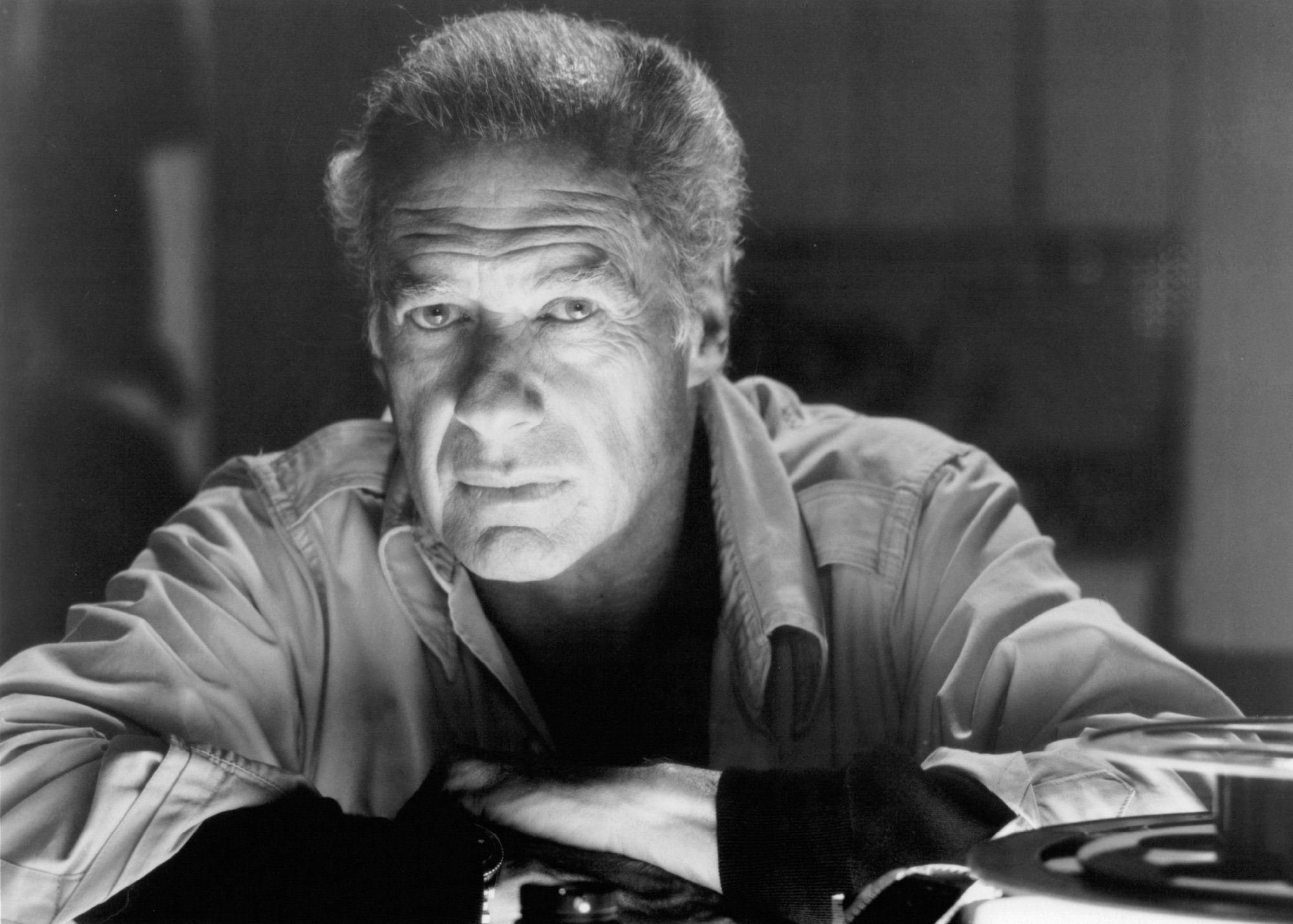

The other key collaborator was Rock Hudson, who had to anchor the entire film. Hudson is nowadays remembered as an old school Hollywood pretty boy, famous for the drama of his personal life outside of the silver screen and his battle with HIV more than for his acting chops; Seconds, though, was a revelation for anyone who had written him off as merely eye candy. It’s an extremely layered performance, and not just for the fact that the film casts him as an ideal of male beauty in a time when he was at the height of his popularity. (If Seconds had been remade in the late 1990s, the role would have had to be played by either Brad Pitt or George Clooney, for example.) Hudson has to play a continuation of the performance started by John Randolph, all while walking through a shifty emotional kaleidoscope of satisfaction, uneasiness, paranoia, terror, anger, and righteous indignation, and he plays it all with pitch-perfect emotional clarity. There’s a scene late in the film when Hudson looks back on the life that he gave up, caught between both regret and a sense of validation for what he did. Ambivalence is extraordinarily difficult to portray as an actor, but Hudson pulls it off with aplomb. Seconds is the finest moment of his career.

And, in more than one way, it may also be the finest moment in Frankenheimer’s. It was not as commercially successful as many of his other films, and it didn’t achieve the level of cultural ubiquity that The Manchurian Candidate ever did, but it’s the film that uses his arsenal of paranoia and thriller tricks to say something lasting and meaningful about a time period. It’s an incredibly cynical statement about how society has completely broken the men and women that make it up, but it’s a definitive declaration expressed with conviction and told in an entertaining and terrifying framework. The final scene of Seconds is as savage an indictment of the 1960s as anything you’ll ever encounter. Going on five decades later, it’s hard to think of many films as merciless in their approach, or as perceivably relevant to the ups and downs that society is still tumbling through. Maybe it’s because so few films in that entire time have been as dark, as twisted, and as weird as John Frankenheimer made Seconds, all the way back in 1966.