The coming of age period in a person’s life is relative, but what it truly represents is the transition from childhood towards adulthood. The process varies in time and in circumstance making it a very unique and special experience to translate through film. In this article, we’ll look at David Gordon Green’s first feature film George Washington (2000), and discuss his approach of capturing young bodies as they navigate adult problems in the best way they can.

Thirteen-year-old Buddy (Curtis Cotton III) is getting dumped by his first girlfriend, twelve-year-old Nasia (Candace Evanofski). This short scene captures the contrasting essence that exists between the dichotomy of childhood and adulthood, establishing the overall experience Green is creating for his audience. Nasia is breaking up with Buddy because she thinks acts too much like a little kid. She says he’s too “goofy” like an “eight-year-old” and she just can’t stand it anymore. All Buddy can think to do is apologize and innocently asks “Can I kiss you one last time?”. Nasia asks him to just tell her that he loves her. The scene cuts before we hear a reply, but it goes on to show two children involved in an adult situation, handling it in the only way they see fit.

Taking place in a small rural town in North Carolina, George Washington follows a group of friends, Buddy, George (Donald Holden), Vernon (Damian Jewan Lee), and Sonya (Rachael Handy) as they navigate their developing perspectives on life and its challenges. Poetically slow shots of children running in the streets, among the debris and desolate, run-down buildings show this seemingly neglected environment to be the community’s playground. Narrated by Nasia, the voice overemphasizes how these friends would “try to find clues to all the mysteries and mistakes God had made”. They were able to focus on finding their peace, separating them from the real world of adult problems. Over a shot of Geroge’s uncle Damascus (Eddie Rouse), a rigid man terrified of dogs, the voice-over continues on to say “the grown-ups in my town, they were never kids… They worked in wars, and built machines, it was hard for them to find their peace.” The generational gap between the children and the adults in this contemporary context raises the idea of this unique coming of age experience that is happening in the here and now of the film world.

George holds the focus of most of the film. He is established as someone special, someone born to be of great importance. He wants to live to be 100 years old and has dreams of becoming the President of the United States one day. His full name, George Richardson, phonetically parallels that of George Washington, anticipating his character to be destined for pioneering greatness. George is physically delicate. He wears a purple helmet to protect his soft skull that makes his head extra sensitive and vulnerable to lethal damage. He is often seen isolated from his friends during certain activities for his own protection, making him stand out even more by consequence. Throughout the film, George can be seen with his rescue dog or other random critters he picks up around the neighborhood, emphasizing his sensitive nature and innate urge to save lives.

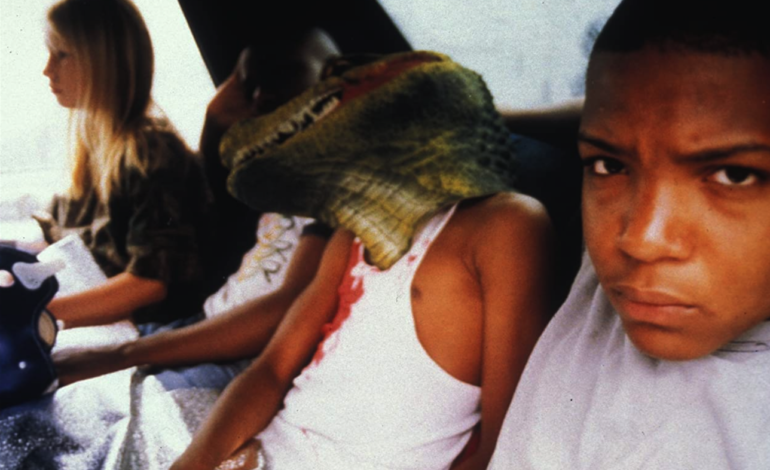

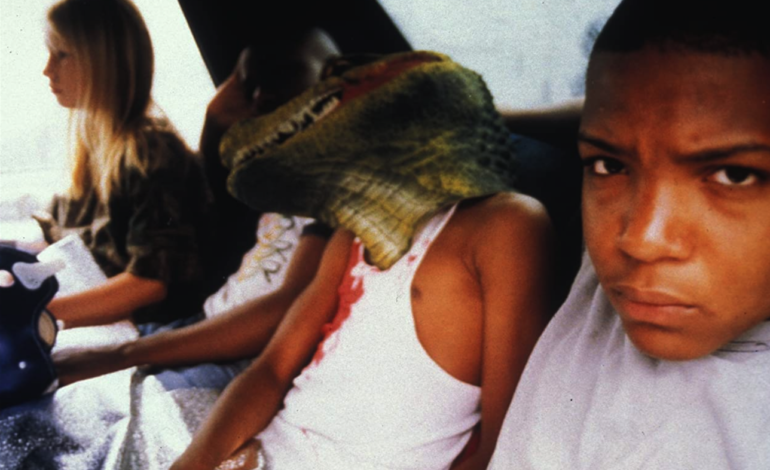

Buddy is introduced to us off the bat as an emotionally sensitive boy. He’s heartbroken over his breakup with Nasia who dumped him for George on account that George seemed older. Buddy claims he gave his all to her – “a plastic ring and a kiss.”. He talks to Rico (Paul Schneider), a local worker, about how he’s handling it. Rico relates to him as an equal, telling him about his own experience with breakups as a young adult. This moment bridges the gap between generations in an expression of mutual empathy for similar experiences that occurred at different times of their lives. Buddy seems to represent a part of this transition that holds on to the imagination, emotional innocence, and freedom of being a child. In an abandoned shack, Buddy, wearing a T Rex mask performs a biblical monologue as if he is on stage. He performs as if he were the son of God himself, eerily foreshadowing his subsequent death.

In a climactic moment of the film, George, Buddy, Vernon, and Sonya are playing in a bathroom. After getting pushed by Buddy, causing George to hit his head hard on the wall, George playfully pushes Buddy back, causing him to slip and hit his head on the bathroom sink, ultimately killing him. The scene presents itself as a catalyzing moment that will expose the transitioning identity of these friends both individually and as a group.

Vernon tries to keep the rest of the group at ease once the group realizes that Buddy is dead. Despite being older, Vernon is forced to confront his own youthful vulnerability that coexists with his growing sense of self-awareness that comes as you get older. In the bathroom, Vernon sits alone, smokes a cigarette, and he breaks down. He is confronted with his own existence and we watch him struggle to balance trying to be a responsible young adult and the childish urge to run away. He scolds Sonya for not feeling anything, forcing her to confront her own apathy that she believes makes her an inherently bad person.

For George, Buddy’s death becomes an opportunity for him to redefine himself as a real hero. He takes Buddy’s wrestling uniform and wears it as his superhero costume with a bedsheet as a cape. Risking his own life, he saves the life of a young boy who almost drowned in the public pool landing him a spot on the front page of the news making him a local hero. The irony lies in the fact that Buddy was killed by George due to a head injury despite having a healthy and sturdy skull (unlike George). George’s heroism teeters on the line between childlike imagination and adult responsibility placing him in the stark middle of this transition as he embraces his individuality and pursuit of greatness, begging the question: what really makes a hero?