Last week, we got major news regarding the futures of Blade Runner 2 and Alien 5; we know their directors and at least some of their stars. These movies, combined with this summer’s Terminator: Genisys, mark a different type of major sci-fi franchise than what regularly hits theaters. Unlike re-starting from zero as a remake/reboot/reimagining (as with RoboCop and Planet of the Apes), these properties are continuing the stories that started nearly 30 years ago. Unfortunately, as the ongoing Alien and Terminator franchises have shown, this isn’t necessarily a good thing. But maybe the upcoming movies can reverse the trend. There’s something significant in these properties that continue to latch onto the past, and hopefully the new installments can recapture the “it” factor that has enabled them to survive for this long.

After more than three decades, Alien (1979), Blade Runner (1982), and The Terminator (1984) are still heralded as groundbreaking classics not just in science fiction, but in popular cinema at large. Aliens (1986) and T2: Judgment Day (1991) have similarly earned spots as genre icons. Even today, they are discussed more than most of the sci-fi action films of the 1990’s, 2000’s and 2010’s. They are pop culture landmarks, and rightfully so. These five movies have earned their legacy by being about something more than effects and action sequences, a lesson forgotten by a lot of more modern movies, even their own sequels.

These five films, along with many of their 1970’s/1980’s contemporaries, were based on and inspired by the works of classic science fiction authors such as Robert Heinlein, Philip K. Dick, and Richard Matheson, writers who were as interested in the infinite possibilities of science fiction as they were with how mankind would respond to and be changed by new technology and discoveries. As cultural artifacts of their time, it’s impossible to miss in the influence of the Cold War and the insecurities felt towards the rapidly evolving technology of the time (something we perhaps ought to be feeling all the more strongly nowadays).

But beyond all the sci-fi trappings and immediate sociopolitical resonance, what made them stand out was their human and emotional components. Ellen Ripley, Rick Deckard, and Sarah Connor were presented as more-or-less average people fighting things well beyond their abilities in worlds that were out to get them. Alien presented the endless void of space as among the most claustrophobic places you can be. Even though Aliens switched from horror to action, Ripley had to deal with being 57 years out of time, confronting the Cassandra complex, and losing her daughter. Blade Runner was first and foremost about the existential question of what it means to be – it’s the driving quandary of Deckard, the Replicants, and the Tyrell Corporation. Terminator asked questions of fate and what are we willing to sacrifice to achieve our destinies, while Terminator 2 continued down this path by showing the incredibly negative effects it had on the Connors, as well as highlighting questions of sentience. These movies have lasted because they offer more to think about and remember than the action set pieces.

Unfortunately, the subsequent sequels (Terminator 3 and Salvation, Alien 3 and Resurrection) failed to remember what made the originals so powerful. While the short-lived FOX series The Sarah Connor Chronicles managed to keep the heart and mind of the original Terminator movies, most of what we got in those four movies was mindless action schlock or a hodgepodge of ideas suffocated by studio interference (the greatest legacy of Alien 3).

Yet despite none of these franchises having a genuinely good installment for 25 years at this point (and yes, I’m including the unfortunate Prometheus in the mix), they are all coming back again to a theater near us to try again. I don’t think there’s an inherent harm in more sequels, but the main question is can they be good? The answer: maybe. Everything has potential, it all depends on the execution.

The one closest to us is Terminator: Genisys, the Days of Futures Past / Abrams Star Trek of the Terminator world. Arriving July 1, it completely reboots the first four movies. It has all the characters we’ve grown to love – John Connor, Sarah Connor, Kyle Reese – except everyone has been recast … except for Arnold Schwarzenegger, which offers some continuity but reeks more of a choice made because of brand recognition rather than story.

The idea of a Terminator or a Resistance Fighter going back in time and training Sarah from the start could be interesting, but it makes you wonder what the film is going to offer besides action. Admittedly, we all have a tendency to overreact to trailers, but that’s how the movie has sold itself – a collection of greatest hits from the first two films (“Come with me if you want to live,” “I’ll be back,” etc.). The tragedy of Sarah’s dilemma and even her willingly giving herself to Kyle Reese lose their impact if she’s on board from the start.

But at least we can have some hope with Alien 5 and Blade Runner, if only by the virtue of having minimal knowledge about the projects. Unlike a lot of these movies, the genesis (or genisys) of Alien 5 seems to come from a director’s passion rather than a studio’s franchise obsession. Nobody was clamoring for a new Alien movie until director Neill Blomkamp posted art from a secret Alien movie that he wanted to do but seemed to be dead in the water. The response to the images, even if Ripley did look a bit like Scorpius from Farscape, led to it becoming green lit – though its placement in the Alien canon is still a bit murky despite Blomkamp backpedaling on a comment that he was going to ignore 3 and Resurrection.

However, Blomkamp is one of the biggest science fiction directors working today, and he did it with one movie: District 9. Yes, Elysium was a colossal misfire (even he admits it) and Chappie looks overly maudlin, but he’s a talented filmmaker who uses his movies to speak to higher concepts. Sure, his points are obvious to the point of unintentional comedy, but there’s something almost admirable about a filmmaker who uses the sci-fi framework to make points, as hokey as they might be. Even with the problems I have with Blomkamp’s movies (and the less than enthusiastic response to his latest fare shows that his star is certainly fading), his connection to the project still makes it more interesting to me. I’d rather see the vision of someone’s passion project more than have the studio throw some random guy in a chair just so they can sell the chestburster again. My biggest concern is if they’re going to try to reverse engineer this to be part of some massive Prometheus/Predator multiverse. Then again, it’s not like the Alien franchise can fall any lower than Alien vs. Predator.

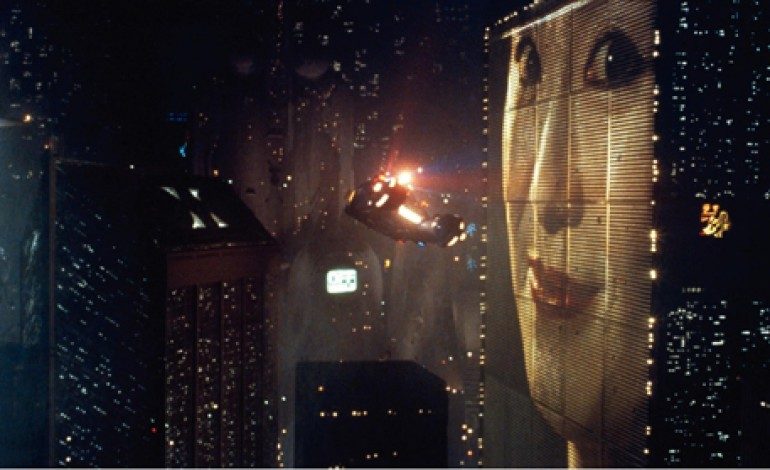

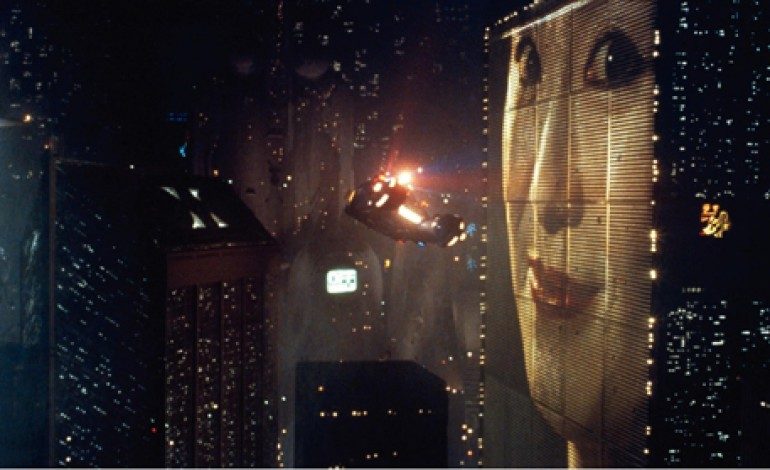

Blade Runner is the most unique of the three (and possibly of all iconic science fiction films) because it’s not a franchise. (While some might argue that the multiple cuts of the movies are a way of franchising the film, that’s not nearly the same as Blade Runner 3: Still Runnin’ or Blade Runner Origins: Batty Begins.) It’s a single story about two men trying to rationalize their reason for being. It never had the chance to become dumbed down action shlock. It never had the opportunity to wear out its welcome. (And it’s also the one that never became financially successful during a theatrical run.) More than any of the other films, Blade Runner 2 has the greatest possibility to live up to (or shame) its legacy. The choice of Denis Villeneuve as a director is a definite plus. He’s a small director who understands intelligent crime drama and noirish atmospheres, which are at the core of Blade Runner‘s DNA.

However, the return of Harrison Ford is definitely a problem. Whether or not Deckard is a Replicant is one of film’s greatest unanswered questions, and having him show up will either answer it or go so far out of its way not to answer it that it becomes distracting. His character is integral to the single movie, not the film’s universe. Deckard (and Batty, for that matter) were just two relatively unimportant people in the Blade Runner universe. The Connors were the savior of humanity. Ripley became important because she was the only person to survive an encounter with the Aliens. But Deckard was just a cop doing his job; exaggerating his importance will only lessen it. Not to mention that the movie should hopefully be above putting him back in in a fashion similar to Arnold Schwarzenegger’s “in the film because the public knows him.”

With the possible exception of Terminator: Genisys, it’s impossible to know how any of these movies will turn out simply by the announcement of a director. But the choices of Blomkamp and Villeneuve have definitely raised my expectations a bit. They are genuine filmmakers, and hopefully they’ll be allowed to present their vision rather than the studio’s.

Besides, it’s not like the 1970’s and 1980’s had a monopoly on personal, sociopolitical, and philosophical issues. It’s a rare day when we aren’t confronted with questions about privacy/security, the omnipresence of the Internet, all our personal information being out there, cyberlives vs. real lives, our increasingly shrinking world, and the eternal universal constant of identity. Films, science fiction films especially, should explore these issues, and a bigger budget and audience should be an advantage rather than a hindrance.

To be fair, there are still many that relish in the opportunity to use science fiction in this fashion, but they tend to be smaller fare. Shane Carruth (Primer, Upstream Color) and Mike Cahill (I, Origins; Another Earth) are two modern filmmakers who successfully utilize the format to produce intellectual and emotional content. The aforementioned Blomkamp has found a big budget niche, while the Of the Planet of the Apes series has successfully followed in the high-minded legacy of the 1968 original by looking at issues of sentience, class structure, and leadership. Recent time travel films Looper and Predestination have been able to put clever spins on a genre that could easily be burned out by now. Even the colossal misfire Transcendence at least tried to be a more cerebral science fiction thriller, but it made the mistake of lightly touching on so many topics rather than truly honing in on a couple of ideas. Will any of these movies be welcomed into the zeitgeist like the core classics from decades ago? Probably not. But at least they’re attempting something more than having a senior citizen destroy a helicopter by jumping out of a plane.