Though Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira’s influence is well-known, its impact cannot be understated. Without Akira, anime as we know and love today, including the likes of Dragon Ball Z, Neon Genesis Evangelion, and other iconic titles wouldn’t exist. Akira pioneered a new standard of visual culture, filled with unfathomable intricacies and hand-drawn detail that just leaves viewers in awe; by the end of the two-hour runtime, I was awe-struck and left wanting more of everything— the visuals, the tumultuous, cyberpunk post-war world and the characters navigating it.

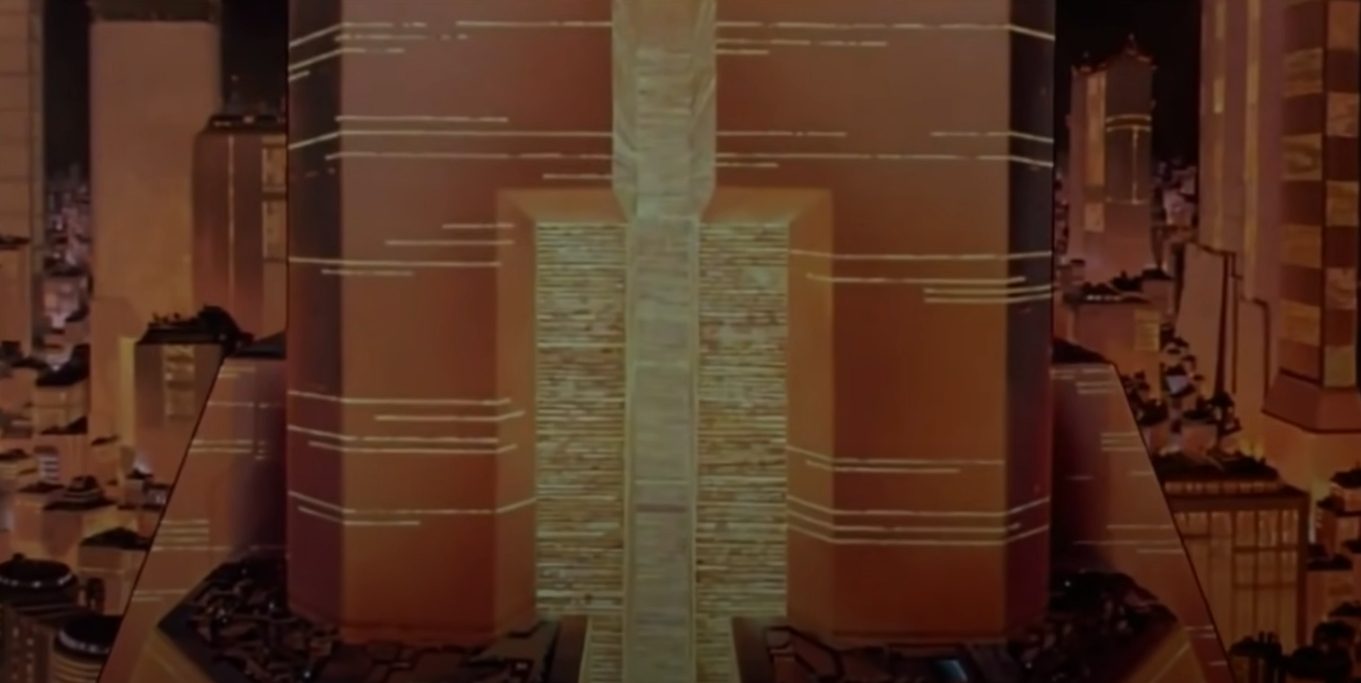

Akira begins with a bang. In 1988, after World War III, Tokyo is destroyed by an unnamed disaster, a clear homage to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and its post-war undertones carry on throughout the film. In 2019, there is Neo-Tokyo, an imagined postmodern, futuristic dystopia boasting juxtapositions of different architectural styles and varying states of decay revealing its highly stratified society. The collective trauma of the 1988 bombing is made clear from the beginning, with the amount of public dissent and protests shut down violently through the military police. Even from the beginning, Akira is a story rooted in familiar social issues, showing Otomo’s consideration of the modern world.

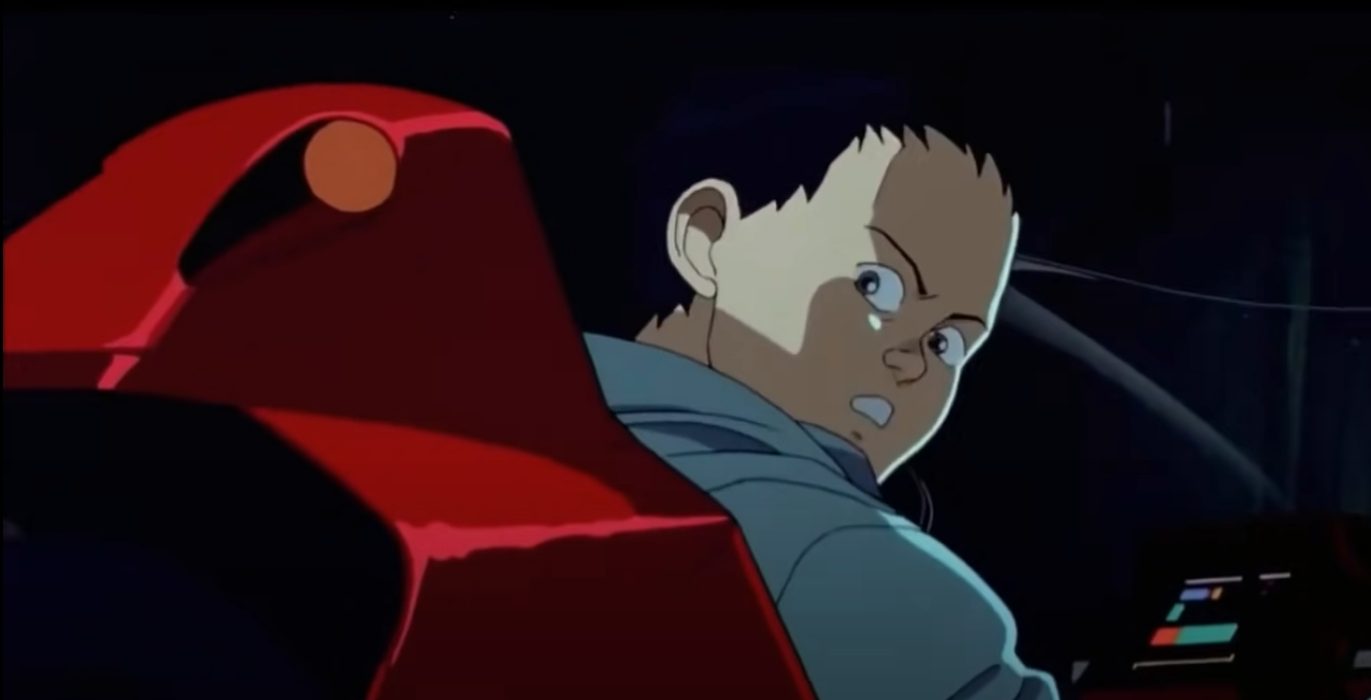

The story grounds itself in a biker gang with protagonists Kaneda and Tetsuo, delinquent school-boys raised in a neglected sector of Neo-Tokyo. After an encounter with a rival gang, Tetsuo gets into an accident involving a visibly hollowed young boy, who is one of the government’s escaped test subjects. This triggers Tetsuo’s underlying psychic powers, and, as observed by one of the leading scientists, Doctor Onishi, Tetsuo’s powers matches that of Akira, whose power is alluded to be the cause of Tokyo’s destruction in 1988. Though Onishi is fascinated, Neo-Tokyo’s military leader, Colonel Shikishima is less enthused, wary of the young boy’s potential.

Already the post-war consciousness makes itself clear in the movie. Traumatized from the city’s past destruction, the leaders of Neo-Tokyo are hesitant towards scientific development of a power they cannot control. Akira raises the question of the extent of scientific pursuits, considering its potential for mass destruction, something typical of post-war films. However, Akira makes the most out of animation as a medium, and portrays all of this through intricate machinery, with elaborate computers flashing neon buttons and animated holograms among other complicated contraptions with countless moving parts.

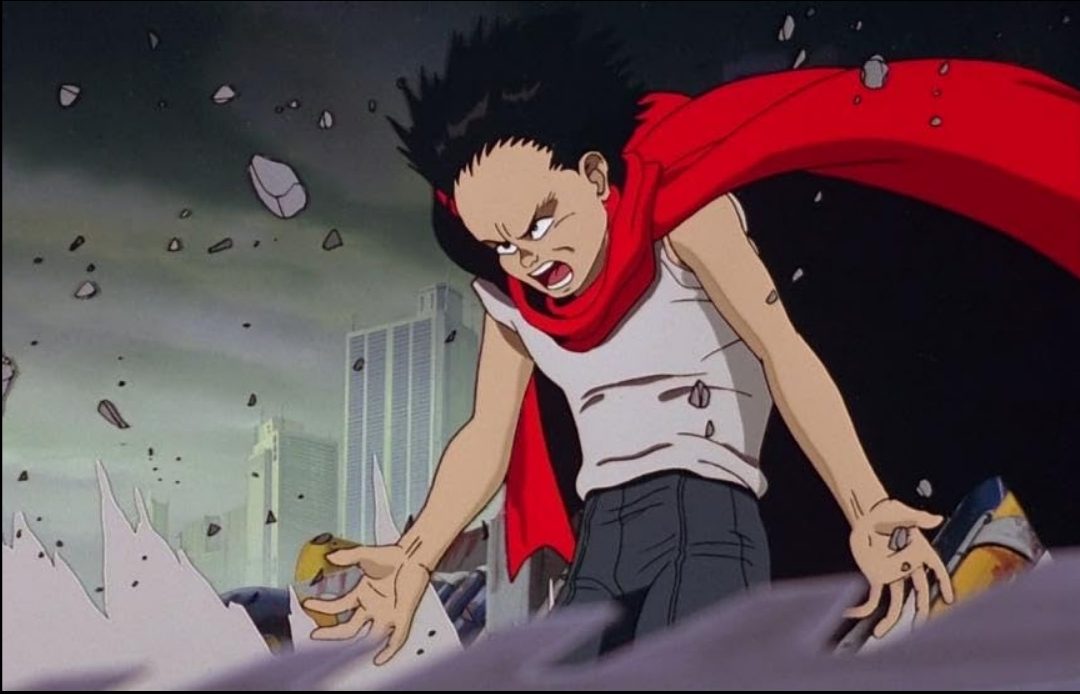

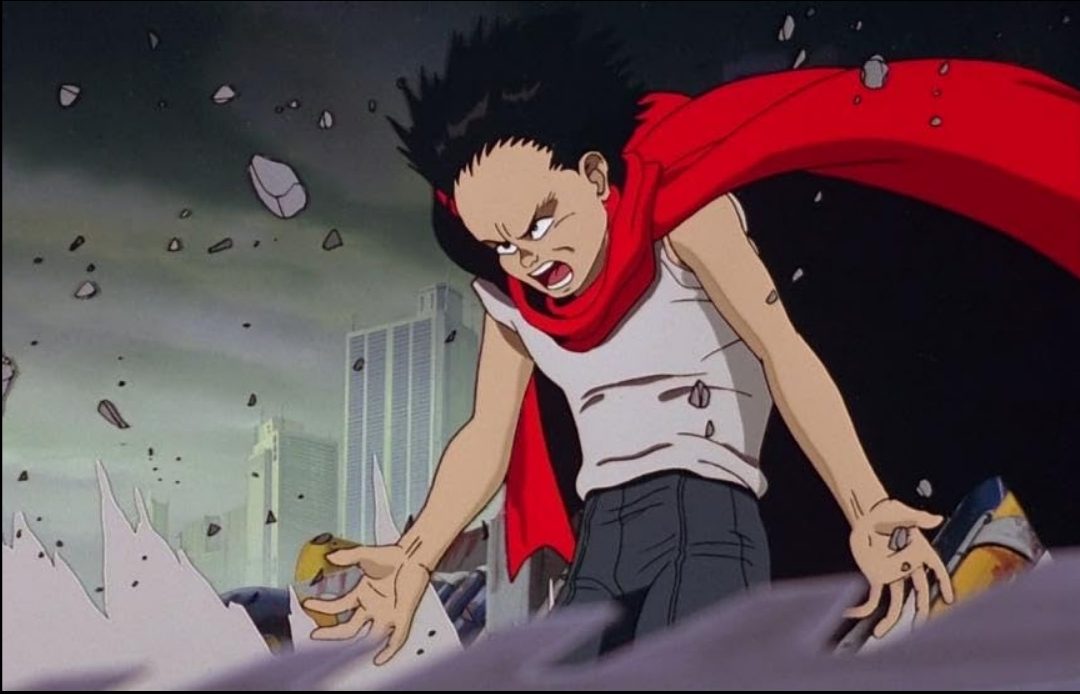

The full scope of Akira’s visuals is difficult to capture in words: from the lively, abundant neon city to its decayed, neglected outskirts; the neat, controlled, intricate machinery to the uncontrollable, visceral, violent contortions; its futuristic, cyberpunk aesthetics to traditional Japan hidden in pockets of the city; the harsh reality of living poverty to outright nightmarish sequences during Tetsuo’s awakening. Akira switches from sleek to gritty easily, in both scales large and small, all the more impressive considering it is primarily hand-drawn. Every frame is a visual delight, with electronic configurations moving into place or speedy highway races through neon cityscapes. Even clouds, smoke, and steam feel alive, whether it is slowly puffing upwards or rendered sharp from all the action in the scene. Every scene is a visual delight, an inspiration to artists and non-artists; it doesn’t take an expert to appreciate Akira.

Unlike family-friendly, pacified Disney cartoons, which dominated animation at the time, Akira took unprecedented risks and care in its art, story, and execution. It had a budget of around 500 million yen at a time when studios normally did not invest in animation, and it paid off superbly well, becoming a launch pad for Japan’s softpower with its influence on modern anime. Akira makes a strong case for investing in arts and media, showing that stories that grapple with difficult subjects are in demand, and that artists, with sufficient resources, can innovate to unparallel extents.

Beyond being a visual triumph, Akira remains faithful to a vision of the future that is human and applicable to post-war life. Kaneda and Tetsuo are kids left in the aftermath of destruction, growing up with minimal care and resources that inevitably led them to a delinquent lifestyle. When Tetsuo realizes his powers, he wrecks havoc with his newfound abilities, relishing at his potential for destruction in a world that previously felt little autonomy in. In the film, we feel Tetsuo’s frustration, a restlessness that resides in the masses shown through their collective dissent and protest against a neglectful, oppressive government. However, beyond the collective, the story is also personal; Kaneda just wants to save his friend. The friendship between the two boys stresses personal relationships within a cruel world, and Kaneda’s dedication to saving Tetsuo perseveres.

Akira takes care in showing how different characters deal with the aftermath of destruction, from the iron-fist rule of Shikishima, Kei’s rebel group, and Tetsuo’s outlash, resulting in subplots that may feel scattered or unresolved. Akira is based on Otomo’s 120-chapter manga of the same name, with plot points compressed in the two-hour runtime, leaving ambiguity and questions after its finale. The story delves more into the realm of science fiction and action in the latter-half, as Tetsuo realizes his power with the technological-advanced military trying to stop him. Still, even with some necessarily excluded character development, viewers understand the restlessness behind the characters, the chaos of post-war society and the characters’ journey in navigating it. The world-building is no less vivid, even beyond its elaborate visuals, its unapologetic depictions of a violent state, social stratification, and dissatisfied public eerily reflects the same issues in the twenty-first century.

And, maybe just as importantly, Akira is, above all, cool. Kaneda’s iconic red-bike, donned with stickers of mass culture and brands, is the understandable envy of Tetsuo, and is still an iconic image in media today with various action sequences paying homage to the “Akira slide”. Akira is unapologetically flashy and stylish in unforgettable grit and fashion. The film’s embellished visual language charms, pioneering the cyberpunk genre into one of action, spunk and tenacity amid a tumultuous world.

In its two-hour runtime and 160,000-something animation cels, Akira manages to impress, stun, and influence. Rooted in societal issues and care, Akira imagines a dystopia with keen attention to reality, while exploring the limits of animation and visuals to envision a stylish, futuristic world of intricate machinery, neon cities and supernatural powers. However, none of that is romanticized in a tech-run utopian fantasy but rather, the backdrop to real-world issues of social stratification and collective post-war trauma told through two unlikely protagonists.