Today, it’s almost impossible to imagine a time when Steven Spielberg’s name was not universally recognized and his reputation synonymous with blockbuster filmmaking. Mention of the iconic director calls to mind images of the smiling, bespectacled, gray-bearded titan of Hollywood, the man who brought us such landmark cinematic events as Raiders of the Lost Ark, Jurassic Park, Schindler’s List, and Saving Private Ryan.

He is a filmmaker so influential that he helped to usher in the PG-13 rating and is credited with practically inventing the concept of the summer blockbuster. These days, the majority of his films can be split fairly cleanly into either lighthearted family fare such as The Adventures of Tintin and The BFG, or serious historical dramas like Lincoln and Bridge of Spies.

But this month’s digital 4K re-release of Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind, which marks the 40th anniversary of the film’s original release, reminds us of a simpler time when Indiana Jones was still a spark in the mind of George Lucas, and Spielberg was an ambitious 28-year-old, fresh off of the unexpected success of Jaws and eager to dip his toe into the science fiction genre and experiment with a story that valued individual fulfillment and curiosity over family bonds.

This was not the Spielberg we know today, and Close Encounters serves as a fascinating time capsule of the director at a point in his life when he was guided not by studio and audience expectations, nor the firmly-cemented beliefs that accompany old age, but rather nothing more than his own creative curiosity.

The seed for Close Encounters was planted in 1973, when Spielberg struck a deal with Columbia Pictures to produce a sci-fi film. Influenced by his own interest in meteor showers and UFOs, the director toyed with a script over the course of several months, bringing in multiple collaborators to write drafts for him as he worked on other projects. Two years later, having defied expectations by making 1975’s Jaws the highest-grossing film of all time, Spielberg was afforded extensive creative control by Columbia, allowing him to fine-tune his UFO story and write the shooting script himself, with help from Jerry Belson.

The key to the story, as Spielberg has said, was making the protagonist an everyday blue-collar worker. Early versions of the screenplay cast the lead character as an Air Force Officer and later a policeman, but Spielberg realized that it would be harder for audiences to identify with a man in uniform.

The answer was Roy Neary, the unremarkably average electrical lineman, husband, and father who stumbles upon a UFO while investigating a mysterious power outage in Indiana and is subsequently driven by an unquenchable curiosity to learn everything he can about the alien visitors. Spielberg explained that he wrote Neary as an extension of himself, basing the character’s reactions and behavior on the way he anticipated he would act in such a situation.

Accordingly, he cast Richard Dreyfuss in the role, an actor with whom he had recently worked on Jaws. Spielberg has repeatedly mentioned how Dreyfuss serves as a Spielberg doppelgänger in several of the films on which they have collaborated, citing a close personal connection with the actor’s mannerisms, physicality, and personality that he has never found with another performer. Based on this premise, it’s interesting to see how Dreyfuss captures the almost single-minded curiosity and passion of a young Spielberg in his wide-eyed performance as Neary.

The protagonist of Close Encounters is a Spielbergian outlier in many ways, a far cry from the flawed but caring parental figures motivated by their love for their families in his earlier films, like Lou Jean Poplin in The Sugarland Express and Chief Brody in Jaws. Roy Neary is a disgruntled, distant and disinterested dad from the start, snapping at his kids when they make a racket while playing and failing to listen to his wife when she tries to settle on a fun activity for the family to enjoy over the weekend.

Neary practically demands that the family see Pinocchio when he finds out it will be playing at a local theater, and this is no coincidence. Spielberg has claimed that he was heavily influenced by the animated movie’s song “When You Wish Upon a Star” while writing Close Encounters, as it evokes a sense of hopeful optimism and fulfillment that accompanies looking to the sky in search of a greater purpose.

Roy’s obsession with Pinocchio hints at the fact that he shares Spielberg’s belief. Following his initial encounter with an alien spacecraft, a curiously jarring affair of bright lights and mechanical malfunctions, Roy cannot help but obsess over his desire to learn more about the extraterrestrials he’s certain he encountered. An analysis of the character begs one to consider the young Spielberg behind the camera, an up-and-coming director who had just had his first taste of superstar success with Jaws and, having been offered significant creative freedom as a result, was hungry to explore the possibilities that big-budget filmmaking offered.

Nowhere in his mind were thoughts of settling down and starting a family, though those would come in time. At this point in his career, the wonder that comes with being handed a camera and told to make whatever you want was enough to consume Spielberg’s attention. This sense of almost childlike curiosity is at the heart of Close Encounters, and Roy Neary personifies it perfectly.

Perhaps one of the scenes in the film that best exemplifies this concept is when Roy drags his whole family out to a lonely stretch of road at four in the morning to try and catch a glimpse of his alien friends. His wife, Ronnie, who has thoughtfully agreed to indulge Roy in his far-fetched UFO tale, puts her arms around him and speaks of a time when the two of them would venture out on starlit nights purely to enjoy each other’s company. As Ronnie lovingly kisses him, Roy’s eyes remain fixed skyward, scanning the stars for something more.

Another image that captures Spielberg’s childlike wonder in a much more literal sense is a shot of three-year-old Barry Guiler staring out in awe at the alien mothership through the open front door of his house in one of the film’s most visually iconic moments. The movie’s inclusion of Barry, whom we see smiling at the offscreen extraterrestrials before being abducted and carried away on the mothership, is notable for its differentiation from Roy’s storyline.

Barry’s abduction leads his frantic single mother Jillian on a desperate journey to make contact with the mothership and reunite with her boy. Jillian’s obsession with the UFOs, motivated by her mission to find her son, stands in stark contrast to Roy’s more introspective quest for self-fulfillment, distinguishing the character even further from the family-focused Spielbergian archetype.

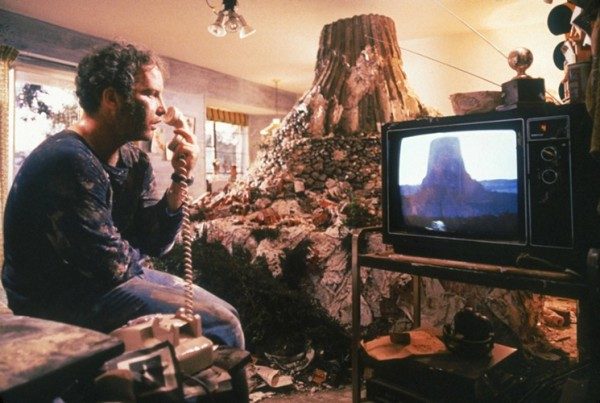

In fact, Roy’s obsession grows unbearably frustrating for his family as he begins to have visions and create sculptures of Devils Tower in Wyoming, the future site of an extraterrestrial landing. As Ronnie angrily protests his behavior, Roy repeatedly breaks down in tears, admitting that he doesn’t know what’s wrong with him. Eventually, Ronnie takes the kids and leaves Roy, who protests momentarily before diving back into his model-making.

When he ultimately travels to Devils Tower and witnesses the film’s climactic alien landing, Roy is chosen by the visitors to join them on their mothership, finally deciding to accept the offer and travel into space with them. The aliens seem to approach Roy with the same reverent curiosity with which he has viewed them throughout the film, and the audience is treated to a glimpse of the normally restless Roy finally at peace, smiling with hopeful satisfaction.

Interestingly, Spielberg has said that he probably would not have ended the film this way if he had written it later in his life, after having kids. As a father, he feels that he could not have written a conclusion where Roy abandons his family and leaves Earth in pursuit of his extraterrestrial obsession. It is a storyline that only a Spielberg in his late twenties could have justified and understood. As he says, at that age he would have made the same choice as Roy.

This conviction is tangible in the final scene, which presents Roy’s exit not as an impulsive act of irresponsibility, but as the logical solution and next step in a life plagued with dissatisfaction and yearning, an answer to the desire for intellectual and transcendental fulfillment that has been driving Roy both consciously and unconsciously throughout the story.

There is a sense of inevitability at the end of the film, as if Roy’s decision to board the mothership is what audiences should have expected all along. It is presented as the only satisfying and sensible conclusion to his character’s arc, and the scene itself, with John Williams’ memorable, brightly hopeful score, the heaven-like image of the small aliens prancing in the white light cast by their ship, and the smile on Jillian’s face as she watches Roy step aboard, casts the moment as a hopeful and heartwarming end to a long journey of self-discovery.

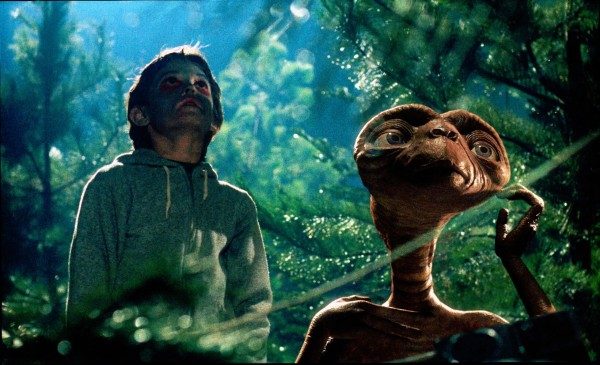

In this way, the scene plays like a classic Spielberg feel-good ending, but a deeper understanding of the weight of Roy’s decision indicates the shift in personal values that was soon to take place in Spielberg’s life. Only a few years later, in his next foray into science fiction, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (which celebrates its 35th anniversary next week), Spielberg would tell a similar story of an alien visitor coming to Earth and bonding with a human.

Though the human protagonist, Elliott, is driven to help the alien due to a psychic connection similar to the one Roy possesses in Close Encounters, at the end of the film the extraterrestrial must return to his people and Elliott must stay behind with his family. Their friendship will live on, but the two know where they belong. Spielberg claimed that he saw the film in many ways as a representation of the end of his childhood, and indeed it seemed to mark an end to his fascination with curiosity for curiosity’s sake. E.T.’s mature, coming-of-age sentiment would carry through many of Spielberg’s later films as he began to develop into what actor Shia LaBeouf once negatively defined as more a brand than a director.

Indeed, in the decades since E.T.’s release, Spielberg has settled into a fairly consistent pattern of churning out dramatic historical films and lighthearted adventures catering to family audiences. One hesitates to say that he has become predictable as a director, but he does seem to be sticking to what has worked for him in the past. There is nothing necessarily wrong with this tendency, and it certainly makes sense for a seasoned director whose techniques and beliefs are probably set in stone at this point in his life.

But as we celebrate the 40th anniversary of Close Encounters of the Third Kind, it’s worth pausing and taking the opportunity to glimpse a Spielberg of a different era, one unshackled by the expectations that accompany a decades-long career. There is something beautifully naive and refreshing about seeing a cinematic giant as merely a 28-year-old motivated by nothing more than his passion for telling stories on film and his boundless curiosity.