The following contains spoilers for Birdman. You have been warned.

Alejandro Inarritu’s last movie was a Spanish language metaphysical trip through life in the underbelly of Barcelona, Biutiful. His current film is an English language metaphysical trip through the American performing arts scene that mines much of the same existential angst, but to more comic effect. James and I didn’t get around to talking much about how Birdman compares to Inarritu’s past work, but that’s mostly because there’s way too much of interest to explore in this movie on its own. There’s stuff to spoil in this movie, which is best seen fresh. If you haven’t had a chance to make it to Birdman yet, you might want to take a look at our review. Otherwise, let’s dive into Birdman.

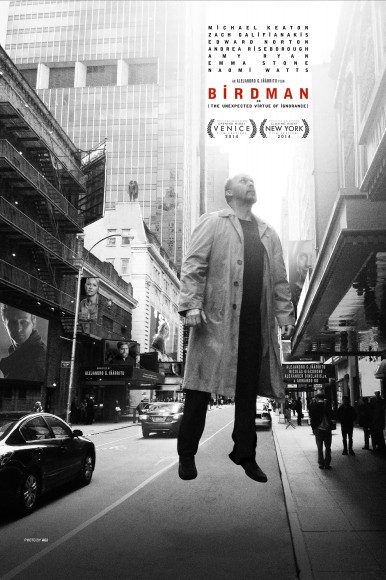

Tim: You know what stuck out to me most about Birdman? How incredibly clever it is, right down to the casting. This would not be the same movie without Michael Keaton in the lead (and he justifies that selection, by the way). I mean, yes, there’s plenty to talk about with regard to the cinematography and a lot of the thematic elements of the film, and I’m sure we’ll get there, but can we start with just a little reflection on how fun it is to watch a movie this clever? I had a grin plastered across my face for nearly the entire movie.

James: Without question. Keaton’s casting itself is a treasure in this unbelievably rich and multi-layered movie. Having the former Batman portray a former superhero movie star trying to go legit on the Broadway stage is a great conceit. Birdman probably could have coasted on being just an industry satire (supporting actors Edward Norton and Emma Stone may have been cast for similar reason considering their comic book movie experience); however, it feels that director Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu and the screenwriters just use that as a jumping off point for a wickedly fun movie about the craft of acting and perhaps about identity itself.

Tim: There are much bigger points to talk about in what you just said there, but if you’ll allow a short quasi-digression, I loved how this movie pointed a comic eye at the craft of acting in a way that’s not frequently seen. You get shows like 30 Rock that have poked fun at actors’ quirks by going over the top, or overt comedies that really lay into how ridiculous method actors can be sometime, but this satire couched in realism is usually something you see more with movies about writers.

James: True, and Birdman does so in such interesting ways. There’s obviously some ribbing going on, but there’s also, I think, a genuine thoughtfulness to the acting process as well. For instance, Edward Norton’s character, a prominent stage actor, has a huge ego and quirks that are maddening, but the film also revels in his brilliance at technique. On another level, it also pokes fun at Norton’s reputation as a difficult actor. That it works on some many simultaneous levels in part of the fun, but also what makes the film stand out.

Tim: Really for me, it was summed up in that first scene with Norton, where his Mike and Keaton’s Riggan are acting out the scene from Riggan’s play together, and Mike keeps pushing Riggan to new territory. It’s such a sweet mix of praising the process and making a joke of it all at once, piled on top of the fact that, as you said, these are actors playing actors embodying some of their own quirks. And man oh man, do they shine. Not to get too awards-y, but I can’t imagine Keaton not getting a best actor nomination, and Norton seems like a good bet for supporting.

James: That’s really a terrific scene. The two of them bring out the best of each other in such surprising and exciting ways. What also struck me about that scene in particular is that even though Birdman lives in a heightened, sometimes surrealistic state, is how realistic and thoughtful it felt. I’d really like to hear how actual actors take to this film, because it seemed like a realistic scene and one that’s not often seen in movies about acting. And, I certainly agree, Birdman should get a lot of Oscar nominations and Keaton’s live-wire performance should be one of the strongest contenders.

Tim: Ok, so I have a question, and it’s turning in a little bit of a different direction, but it ties back to the idea of two ideas sitting next to each other. I think a lot of Birdman has to be read as a condemnation of Hollywood’s blockbuster culture, especially of the superhero variety. And you know what? That’s entirely fair. But then there’s also this Broadway critic character who shows up, the one who’s going to tear Riggan’s play a new one just because she doesn’t like him and what he represents. So here’s my question: I read that as the film acknowledging some need for a balanced opinion rather than steering solely into the, “It must be high art!” sort of New York intelligentsia side of things. And I’m curious: Did you have that reading, too? I saw this with a friend of mine, and I’m not sure she did.

James: It’s certainly balanced. Nobody really gets off clean here. Not Riggan because of his franchise-filmmaking background or his desire to reinvent himself as a legitimate stage actor. Nor Mike, who is a “real actor,” or even the theater critic who has decided Riggan’s play is trash before seeing it.

Tim: In a way, the style in which the film is shot forces a somewhat balanced approach to the whole movie. Riggan is 100% our lead character, but we have to bounce around to a pretty broad supporting cast just to make the transitions work, and all of that cast have some kind of subplot going on that are pretty interesting in its own right. I found myself thinking back through the movie and picking out some bits of the narrative that maybe weren’t essential, but as I thought about it, I still liked most of those bits, and I think it’s because the characters are so compelling and the camera demands we pay attention to all of them.

James: I think you could probably make an interesting movie about any of the supporting players. Which speaks to the talent of the ensemble, but also that Inarritu allows us to share in private moments with all of them at some point in the movie.

Tim: Absolutely. Really well done on both counts (cast and director). Did you know the film had been shot to look like one take going in? We’ve done a fair amount of coverage on Birdman, but whether that was being kept hush hush or if I just missed it, I didn’t know about it. What a thrill when I got about five minutes in and realized there hasn’t been a hard cut.

James: I did know going in, even though I tried pretty hard to avoid reading much about Birdman before I watched it. I was a little worried from the start it might seem like a gimmick or it might be distracting, but in the end it just seemed like it made everything so much more fluid and alive. Not to get back into the awards conversation, but cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki (who won last year for Gravity) must be considered a frontrunner, right?

Tim: Cinematography Oscar bait if I’ve ever seen it, I can’t imagine he won’t win. But that doesn’t stop it from being great. I thought it complemented the sense of heightened reality you discussed earlier just perfectly, and when the moment came for Riggan to really start tripping out, it meant the movie didn’t skip a beat. Tonally, it just works, it ties together the sudden helicopter explosions and Riggan flying, then shifting right back to him merely standing on the edge of a building. I couldn’t have predicted it would work so flawlessly before seeing the movie, but now I don’t see how anything else could achieve the same effect. It just feels effortless, no need for some hokey effect to tell us what’s a daydream and what isn’t.

James: I absolutely agree. The one-shot conceit actually gives the film a complete dream-like quality. One other thing I really loved about the way it was shot goes back a little bit to what we were talking about earlier on terms of the acting process. It was such a thrill to watch these performers and see them actually acting together. In the majority of films, it’s usually cut and cut and cut with lots of noticeable coverage taking place. Here, the performers are actually acting together and every moment (and emotional cue) is accessible.

Tim: Yeah, that was really fun. Edward Norton you kind of expect to be good, and Michael Keaton, you figure he’s got it in him. But then there are people like Zack Galifinakis, who’s flashing dramatic talent everyone who hasn’t seen Visioneers or It’s Kind of A Funny Story (so most people) probably didn’t know he had, and Emma Stone, who I was already a fan of, who turns in what might be a career best performance. But to close the cinematography loop – it’s actually really funny, the part of the film which is, in fact, most dreamlike is actually the only part of the film that has hard cuts.

James: And that might just be a meta joke too. It’s strange, I’ve seen the film twice now and I still feel like I’m only slightly scratching the surface of what Birdman is really aiming for thematically and stylistically. All I am really sure about is that I loved it.

Tim: Well I loved it too – except for about the last five minutes, from the point where Riggan shoots himself. And if the rapid cuts are just a meta joke, that’s depressing to me. But back to the point, I do not understand what the ending is trying to add to the movie. I flat do not get it. Don’t know what else to say, except it didn’t seem to quite fit. Help?

James: I’m not sure how much I can help, but I’ll try. The logical read is that Riggan fell to his death and that may very well be what happens. Since Birdman mentions Icarus and a few other highfalutin’ ideas throughout the film, I think it’s meant to be seen in a more poetic eye. That Riggan has embraced the Birdman image and perhaps has even succumbed to it entirely. I’m not entirely sure I completely understand it, but I felt moved by the final shot both times I saw it.

Tim: I really want to see the movie again, and not just for the ending, but that would help. I think one possible explanation is that Riggan has somehow reconciled his artistic self with his Birdman self, in that his new nose makes him look more like the iconic character, but it was achieved by a method that was critically praised, but I’m not sure the ending really lands if that’s what it was going for. I also thought is was both kind of funny and highly uncomfortable that the thing he’s praised for, the “new art form,” is live self-mutilation. I’m frustrated because it does seem like there was something very specific in mind that the movie just doesn’t quite deliver on. Actually, the film I’m most reminded of is Fight Club, another movie that ends with the protagonist shooting himself, and another movie where I think the ending is complete crap (although I like Birdman waaaaaay more than Fight Club on the whole).

James: Certainly uncomfortable (and strangely funny) that Riggan’s biggest artistic success is shooting his nose off his face. I was thinking he committed suicide on stage at first – and maybe he did; perhaps the rest was some sort of post-death epilogue. Yet I still think there’s value in the actual ending even I’m still a bit unsure of how to process it.

Tim: I had considered the death-dream possibility, and I don’t buy it because part of the scene is from Sam’s perspective. I can’t decide if I wish it ended with Riggan’s death on stage, though, or not. On one hand that’s somehow appropriate. But on the other hand, it seems both artistically bankrupt and something that Riggan hadn’t yet been pushed far enough to legitimately consider, not yet, and I think that’s part of why him jumping out the window felt a bit off to me as well.

James: I like the idea that Riggan has reconciled his reality with the fantasy of Birdman. Still slightly unsure of how precisely I feel about, I think the ending is supposed to represent some of cathartic blend of the two. And either he flies at the end or fell to his death. Either way, I think it’s a nice touch that Sam is rooting for him either way.

Tim: I can buy that sentiment, I think. As I suppose is clear by now, I wish that those last few moments had been as precise as the rest of the film, but the more I think about it, the more I can live with it. It doesn’t dramatically change the thematic nature of the film, for example; as you say, it’s actually a very natural progression from where the characters have been, or at least it seems like it could be.

James: And whatever the case, I’m just grateful that such a film exists in the first place.