The Congress is the kind of sci-fi film that rarely gets made anymore. Most science fiction films craft a future, be it beautiful or horrible, and attempt to distill a human response to that future. What if we built clones, or sentient robots, or a machine that travels through time? The Congress takes an inverted approach. It examines what we want, as families, as businessmen, as people, and then it crafts a future to match those desires. The film is a dizzying blend of live action and animation, and it doesn’t always come together, but what it lacks in narrative clarity it more than makes up for in pure cinematic beauty.

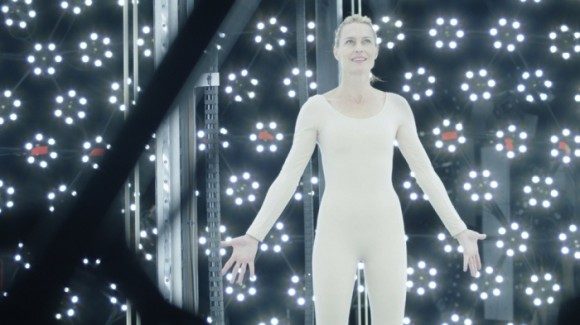

The film opens on an aging Robin Wright (The Princess Bride, House of Cards), playing a fictionalized version of herself whose career has spiraled into nonexistence following a string of bad choices and is living in a repurposed airplane hanger with her two children: Aaron, who is slowly going deaf and blind, and Sarah. With all her options exhausted, her agent, Harvey Keitel (Reservoir Dogs), brings her to meet the head of Miramount Studios, Danny Huston (X-Men Origins: Wolverine). She agrees to sell the rights to her digital self, a perfect computer copy that the studio can animate.

Flash forward twenty years. Robin’s animated character has become an enormous success. So much so that Miramount not only wants to renew her contract, they want her to be the poster girl for the Futurological Congress, the unveiling of a new technology that allows people to turn themselves into animated avatars, transforming into anything they want to be. Miramount wants to sell the rights for people to turn themselves into Robin Wright. Soon she finds herself lost in a world where physical creation has been replaced with imagination.

Director Ari Folman’s last film, Waltz with Bashir, was celebrated not only for its unflinching examination of 1982 Lebanon War but also for its striking visual style, becoming the first animated film to be nominated for an Academy Award in the foreign film category. In The Congress, Folman cements his reputation as a master of animation, creating a world that is lush, imaginative, and not quite like anything you’ve ever seen. The closest analog I can think of is Bioshock’s city of Rapture (for all you gamers out there). It’s a world unbound by physics, limited only by the extent of imagination. It’s feast for the eyes and makes The Congress a film that begs to be seen on the biggest screen possible.

But the film doesn’t start in this Technicolor dreamland; in fact it takes its sweet time getting there. The film’s first act is a struggle through overly theatrical dialog and blatant exposition. It’s a dull opening, and unfortunately not one that becomes richer upon reflection. Keitel’s performance as Wright’s agent is admirable, but ultimately unnecessary in a film that is probably ten minutes too long. Her son Aaron exists primarily to give a Robin someone to look for in the animated world, a flimsy reason to explore the future. Worst of all is her daughter Sarah, who has no bearing on the plot and exists for no reason whatsoever.

These narrative issues never go away, but once Robin falls into the animated world, attending the Futurological Congress, they take a back seat to the larger ideas the film is exploring. This is where the film’s true interests lie, and it does a good job exploring the implications of a world where people can be anyone or anything they want to be. It’s a beautiful and chilling view of the future – beautiful in it’s majestic impossibility, chilling in it’s horrifying plausibility.

Verdict: 4 out of 5

The Congress is bound to be a polarizing film. It grasps at very big ideas, often at the expense of subtlety and narrative logic. The portmanteau of Miramax and Paramount into Miramount is neither clever nor necessary, and the film harps on the notion of free will, giving us no fewer than three monologues about Robin’s bad choices. There are larger issues with the narrative. The film chews through technology and ideology at such a rapid rate, that by the time you wrap your head around the implications of one idea, the film has moved on to the next.

This is definitely a film that will benefit from multiple viewings and, ultimately, that’s the biggest compliment I can afford it. The Congress is an imperfect film, but it’s a challenging one. It never slows down for its audience, instead challenging them to keep up. The Congress makes some missteps but it takes risks and endeavors to show us a world we haven’t seen before. If more films were willing to be so daring, your local theatre would undoubtedly be a more interesting place to be.