In popular media, “the male gaze” is identified as a way to promote male dominance and sexually objectify women. In cinema, the male gaze is shown through conventional female stereotypes (e.g., women strictly as romantic interests, homemakers, dependent on the male protagonist for purpose, etc.). The male gaze popularizes misogyny and ignores the gender spectrum, which fetishizes and parodies queer couples. The more audiences are exposed to these messages, the more they interpret them as truth and have misconceptions about female and queer characters and concepts.

As a counter to the male gaze, the female gaze was coined in the 1970s by feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey and highlights other perspectives different from the typical heterosexual and male-centric point of view. But don’t let the term confuse you; the female gaze features various types of love, friendships, and freedoms by characters representing different sexual orientations and gender identities. From the films of Greta Gerwig to Céline Sciamma, stories have the potential to be sensual, respectful, and thought-provoking without closing off any one group of people or diminishing their overall value to only their appearance.

It is also helpful to consider the “gaze” as the target audience for a particular film. If something is targeted at a male audience (I’ll mention a Michael Bay Transformers movie to indulge in the stereotype), you would find most female characters in skimpy clothing and lighting that complement their physique. Meanwhile, they contribute almost nothing to the plot, and their attraction to the main character allows audience members to fan over them. Gal Gadot in Fast and Furious (2009), Margot Robbie in Wolf of Wall Street (2013), and Scarlett Johansson in the Marvel Franchise are just a few examples of female characters subjected to the kind of sexualization aimed at male audiences.

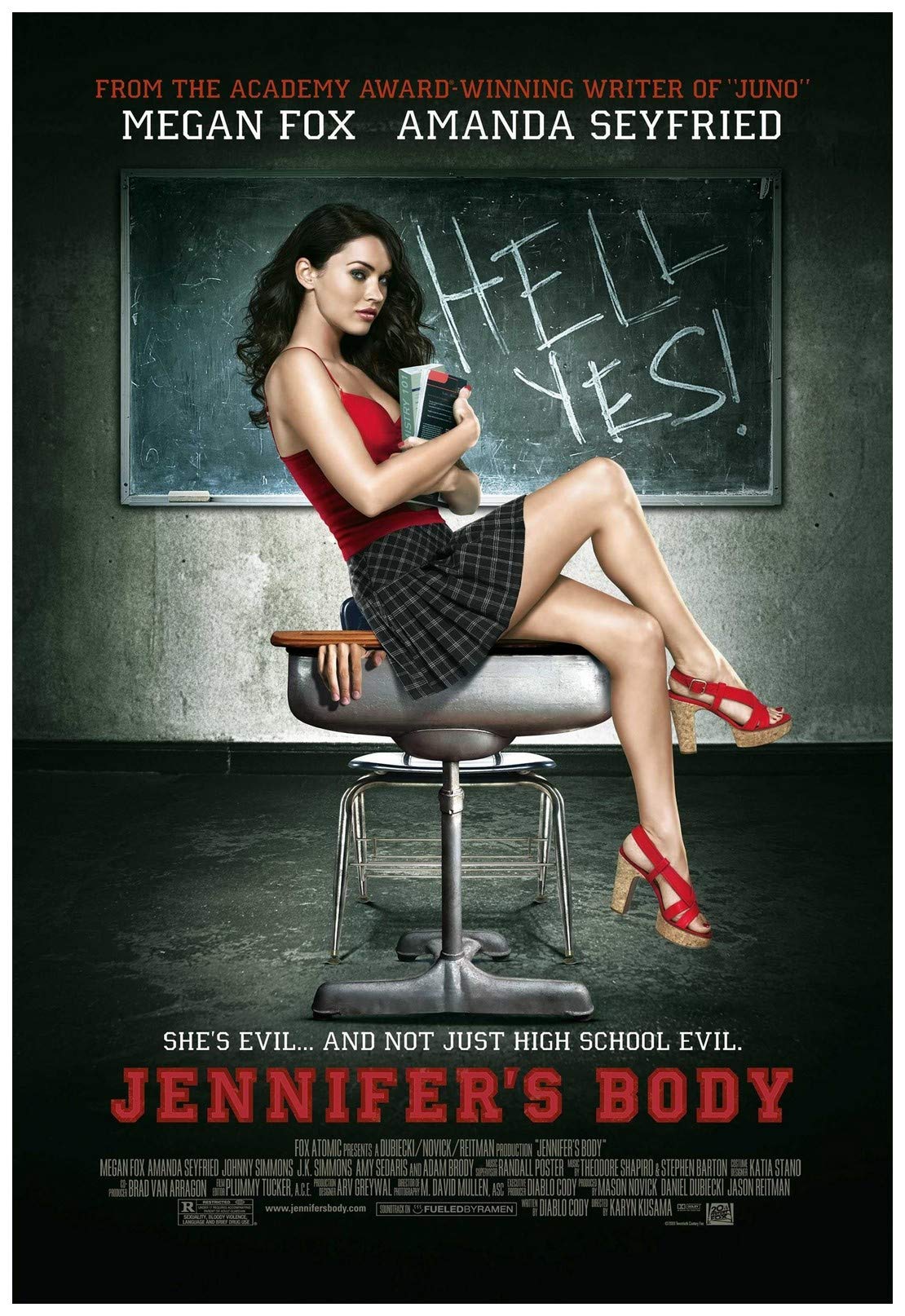

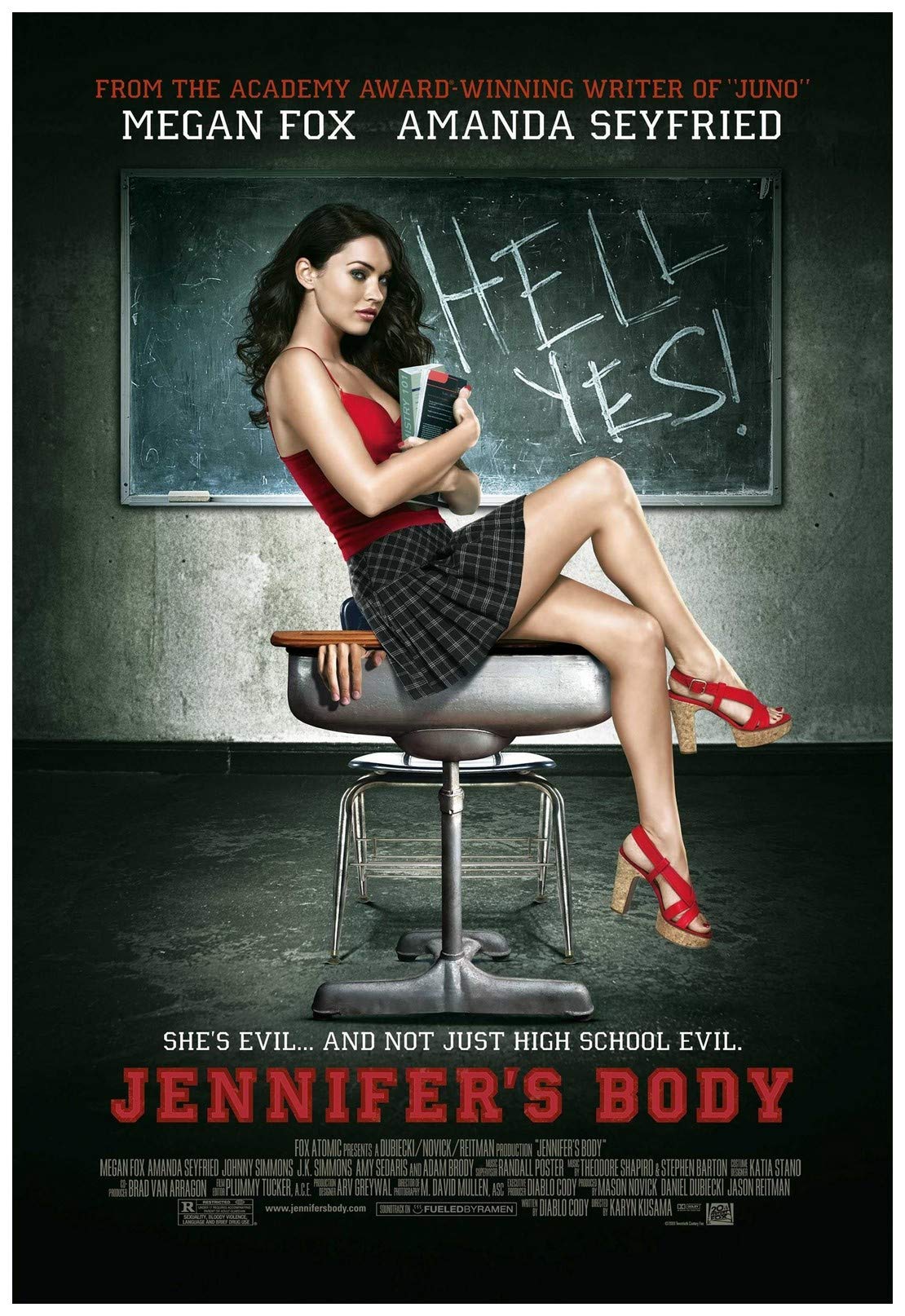

When director Diablo Cody tried to make the feminist camp film Jennifer’s Body (2009), the studio turned the target audience from the intended teenage girls to teenage boys, which caused a massive sexualization of the main character, Jennifer, as seen in the poster below.

In addition to screenwriters creating characters who feel real and multidimensional, a lot of power rests in how the film is marketed and what promises are made to audiences through its trailers. And one can’t start writing to the female gaze unless one acknowledges all the biases forged by the male gaze and the continuous control we afford filmmakers who push for it. Sam Levinson is a primary example of a director who has been subjected to various controversies in recent months. In addition to the leaked information about his objectification of Euphoria actress Sydney Sweeney, he’s recently written and directed the new HBO series, The Idol, which premiered this month. The Idol centers around an up-and-coming singer, played by Lily-Rose Depp, as she navigates the cutthroat music industry and submits to the control of a crazy music manager, Tedros, played by Abel Tesfaye (A.K.A The Weeknd).

It was first developed as a feminist drama written by actor and filmmaker Amy Seimetz, who ultimately left after the filming of several episodes because the storyline was too focused on the sexualization of Lily-Rose Depp’s character. Sam Levinson was then brought on under the recommendation of The Weeknd, an executive producer, and co-writer on the show. This decision supposedly prompted the exit of crew members involved with the project because it was too objectifying and graphic for the story they were initially trying to tell.

The drop in ratings and subsequent cancellation of the second season is proof that this change of leadership was a mistake, but more so, it’s a clear indication that the male gaze is a dominant narrative that is intentionally sought after by many male filmmakers in power. We’re left to wonder what a feminist-oriented version of the show would’ve looked like and are instead left to view deeply disturbing sex scenes and a premise that loses itself in an artist trying to fictionalize his own life.

Just as feminism itself has earned a negative connotation that has been weaponized and used in arguments against gay and transgender people, the female gaze has the potential to be a way of focusing on stories of white cisgender women. This statement has an air of truth to it, as all artists and creators of popular media are responsible for the efforts to break through additional methods of stigmatization. Female gaze stories can have male protagonists (like in Charlotte Wells’s Aftersun) and male directors (Ridley Scott in Thelma & Louise). The real value comes through how these stories are told. For instance, do all of the characters feel active and seen, regardless of their identity? Are they conflicted? Flawed? Human?

It might sound like a low bar, but as we’re witnessing currently with The Idol, battles over quality female characters still need to be fought. Shows geared toward young adults are especially valuable because teens see examples of how to behave based on the media they consume. It doesn’t mean we can’t tell stories that involve misogyny or objectification, but we must look beyond and tell of the effects of such harmful ideologies in our broader society. If not, teens will continue to watch Euphoria and become desensitized to the brutal nature in which misogynistic concepts are displayed without apology or further reflection.

Detecting the male gaze when it appears will help us confront those negative ideas and voluntarily select media that supports inclusion and diversity. For example, the Bechdel test is a safe way to determine if your media supports a diverse audience. If two women talk to each other in a film and the conversation doesn’t revolve around a man, it passes with a stamp of approval. When applied to the most successful Hollywood films, the number of failures might surprise you.