May in the Summer is one of those movies you wish was better than it actually is, and as you leave the theater try to convince yourself that it’s so and you’re not just kidding yourself. The core of this movie is a family drama about a young woman’s engagement to a fiancée her mother disapproves of. Familiar enough, but set against the backdrop of fierce religious and cultural motivators, the complications of a blended family, and, oh yeah, the middle east, the concept takes on added poignancy that should propel it to something truly memorable. All of those factors bring the movie halfway there, but the quality of the filmmaking itself leaves May in the Summer as a film that is always lacking the punch its subject matter ought to provide.

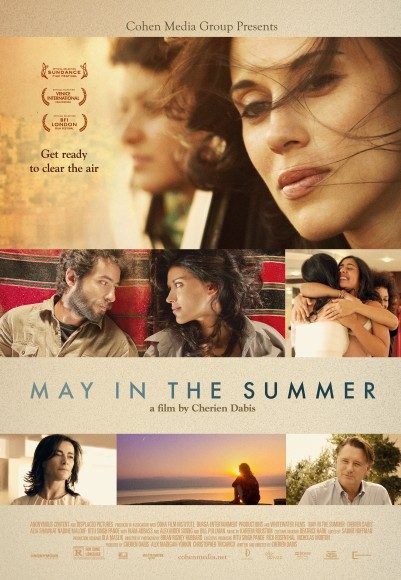

Our main character in this drama is the titular May (Cherien Dabis, who also wrote and directed), who opens the movie by returning from New York to her childhood home of Amman, Jordan in advance of her marriage to Ziad (Alexander Siddig), a Palestinian Muslim whom she met in New York while working on a book about Arabic proverbs. While proverbs appear written out on screen as chapter markers through the film, it’s the “Muslim” part of May’s fiancée that is the more poignant detail. Instead of playing into the larger issues of Israel vs. Palestine or Islamic extremism, however, the tension comes from the fact that May’s mother Nadine (Hiam Abbass) is a Christian, and strongly disapproves of May marrying outside her culture and religion (although May herself is decidedly agnostic). May sees this as hypocritical, given that her own estranged father (played by Bill Pullman) is a white American, and by all appearances atheistic, although this is also a point of evidence for Nadine given their divorce. May predictably rebels against her mother’s disapproval, which only complicates the fact that she’s hiding her own misgivings about the marriage from her family, including younger sisters Yasmine (Nadine Malouf) and Dalia (Alia Shawkat).

This is the pressure cooker we’re thrown into, built in countdown (the wedding is in a month when the film begins) and all. The movie should be commended for trying to tackle so much, particularly because each element is tied to its characters (something too many films sorely lack). Religious conflict hits on two fronts, as Nadine reacts both to May’s choice of husband and all three daughters’ spiritual indifference. Family issues abound, not the least of which is May’s and her sisters’ struggle with feelings of abandonment when trying to reconnect with their now-remarried father. Then there’s an all-too-timely reminder of the constant regional tension, as the girls hear fighter jets scream overhead while at a resort across the Dead Sea from the West Bank. The movie even wades into sexual politics late on, as [minor spoiler] Dalia’s sisters push her to admit she’s a lesbian.

In fact, one of the film’s issues is that it tries to do too much. Rather than weaving together in support of May’s story and character arc, they compete for space. Going back to the scene where the sound of jet engines interrupts the peace of an idyllic resort, they also interrupt an argument between May and her sisters. The jets become the incongruous and abrupt ending to a scene that should have done more to let the audience inside someone’s point of view, ideally May’s. The notion of armed conflict in the region is not one that ever becomes significant to the film. The jets come off as a contextually appropriate but insignificant writer’s trick Dabis used to get out of a scene she couldn’t find a real ending to.

This begins to get into a larger issue at play with the movie. This is May’s story, and her character arc is largely an internal one. That means we as an audience need A) see every scene she’s in from her point of view, and B) have plenty of active scenes for her to actively show what she’s feeling inside, or at least rile her up enough that she’ll actually talk about what’s bothering her.

In the case of the former, the script must shoulder some of the blame, but the bigger culprit is the camera itself. Time and again, we’re shown scenes from an outside perspective, and see the reactions of the characters around May rather than staying with her. There’s a scene early in the movie where May stumbles, drunk, out of a club and meets Karim, a local adventure guide who becomes her friend. We eventually come to realize that May’s extraordinary state of inebriation was driven by her own insecurities about her family, and more importantly, her fiancée, but the camera keeps its distance from both Karim and May throughout this scene. We’re not shown May’s reaction upon encountering Karim, nor how May might perceive him. (Lover? Threat? Friend?) There’s a lack of energy because the audience is removed from May’s experience in the scene. Karim represents something highly provocative – a nice, Jordanian man who could compete for May’s affections (though thankfully the scene remains mostly platonic).

An even better example comes near the climax of the film when May gets into an argument with her mother, Dalia, and Yasmine, and storms off down a flight of stairs. From May’s perspective, it’s an incredibly emotional interaction, but upon leaving, she’d have very little knowledge of how her mother and sisters reacted. But instead of staying on May as her family recedes into the background, the camera remains on the family and all we see is May’s back. The scene probably worked great on the page, but it’s poorly translated into a compelling piece of visual art.

Caught up in all this is the aforementioned notion that we need active scenes to reveal May’s internal struggles. That same climactic scene, with May, Dalia, Yasmine, and their mother chasing each other around a hospital, is about as close as we get. Instead, May plays tennis with Karim and we get a corny sports montage, then they stop and talk. May visits her father and they stop and talk. Each scene has a formal excuse for characters to be where they are, but most lack physical interaction with the environment. It ends up being a very chatty film that never achieves as much true character development as it needs.

The Verdict: 2 out of 5

May in the Summer has a whole lot going for it, but in an embarrassment of thematic riches, it seems to lose sight of the core story it set out to tell in the first place: May’s story. Encapsulated in the question of, “Should I get married to the man to whom I am engaged?” are questions of faith, and of religion, and of family, and of identity, but too often they’re explored on a superficial level. There’s a desire here to push beyond that into meaningful comments on a host of important issues, but along with diversions in the narrative vision, technical shortcomings in the filmmaking would still hold it back from much of the poignancy that May in the Summer perhaps ought to possess.