The filmmaking siblings Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne may be far from household names for those who don’t frequent film festivals, yet they have fashioned a remarkable career telling intimately scaled, socially acute dramas for the better part of the last two decades. Perennials at the Cannes Film Festival, the Dardennes have shared four prizes for directing and screenwriting throughout the years. Past films like The Kid with a Bike (2011), The Son (2002) and their Palme d’Or winning movies L’enfant (2005) and Rosetta (1999) all revel in the small, easily relatable moments with characters (typically on the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum) who are grappling with issues like family, money, work, and sustainability. Their latest, Two Days, One Night is not much different but comes with a hook, something atypical in the Dardenne filmography, in that it’s headlined by the glamorous, Oscar-winning international movie star Marion Cotillard.

While Cotillard’s presence is something new for the Dardennes, who usually fill their casts of either non-professional or local actors, it does nothing is to distract from or distort the mesmerizing intimacy of their latest film, nor does it bastardize their point of view. The Dardennes make Cotillard a convincing everywoman, important for a movie that glides on the lived-in moments of quietly observed life. For her part, Cotillard blends beautifully into this naturalistic tale as Sandra, a wife and mother working at a local solar paneling factory. The story begins as Sandra learns she will laid off due to downsizing by her company. A vote taken by her 16 co-workers pitted Sandra’s employment versus everyone else’s annual €1,000 bonuses; the latter won.

It’s the first scene of the movie and an event that many might find hits uncomfortably close to home in the age of an unsteady job market around the world. Sandra almost immediately resigns herself after hearing the news. We learn a short time later that she’s been suffering from bouts of depression – she has a healthy supply of Xanax to vouch for that – which has led to her missing work in recently. It also seems this may have been a motivating factor for her colleagues, perhaps unfairly spread by a factory foreman. It takes convincing – from a friendly co-worker (and one of only two who voted in her favor), her husband Manu (Fabrizio Rongione, a Dardenne regular), and her own reflection of the reality that without her salary her family will struggle to stay afloat – for Sandra to demand a second ballot to save her job. Thus starts her “two days, one night” journey to try and convince her co-workers to forgo their bonuses so she can save her job. As such, the Dardennes mark Two Days, One Night with the precision and tension of a thriller.

The Dardennes’ innate sense of humanity and yearning for a real-world sense of authenticity makes this part character study/part road movie something completely unexpected and rather exceptional. Sandra has no Erin Brockovich-like monologues and even chastises herself a beggar woman. She is continually at odds with herself over facing her peers. Her co-workers are never portrayed as cartoonish, opportunistic monsters either, running the gamut from sympathetic to hostile with most in that trickier, more complicated grey area in which they understand Sandra’s condition but have their own private responsibilities (and finances) to consider. One man sobs at the betrayal he felt in voting against the first time while another, a supposed friend of Sandra’s, refuses to even hear her out. All of which makes Two Days, One Night a far more complicated and insightful movie than its simple premise would suggest. You might think the repetition would bog down the film in some way, but Cotillard and the Dardennes inject truth-filled careful examination into every square inch of the movie.

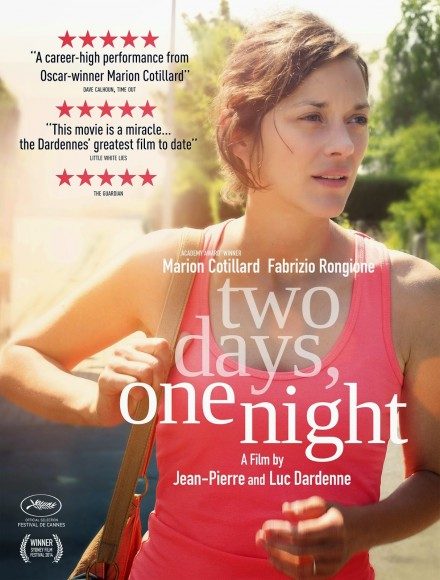

Of Cotillard’s performance, it’s one of the most accomplished on the inventive French actress’s résumé. Her Sandra is visibly on edge throughout most of the film and seems to ready to go over nearly any minute, yet Cotillard modulates her with an unwavering sense of commitment. In Cotillard’s hands, Sandra’s plight is compelling in its utter ordinariness, and Cotillard delivers a performance so naturally lived-in and rooted in straight-forward honesty that she naturally blends into the working class world that the Dardennes specialize in. Dressed down in tank tops and with a scrunchie tying her matted hair, we forget this is the same person showcased so beautifully and grandly in Dior ads.

The filmmaking on display in Two Days, One Night is low key and unfussy, nearly documentary-like in that captures a fly-on-the-wall level of intimacy, primed with a “this is how we live now” sensibility that never for a moment feels false or manufactured. As such, it might be easy to dismiss just how accomplished the film is – the performances, clipped writing, fluid cinematography, crisp editing, and sparse music – as it weaves together into a wonderfully crystallized gem of the human condition. It’s about as far as you can get from the polished temperaments and forced “messaging” typically manipulated in Hollywood dramas. Sandra is no Norma Rae, just a normal working class woman striving to maintain the status quo, not change the world.

The important take away here is that there’s no bad guy or good guy and really, there may not even be a winner at the end. The Dardennes offer no judgments nor easily digestible sentiments, just real life in all its complicated and unvarnished ordinariness. The result is one of the strongest movies of the year.

The Verdict: 5 out of 5

Buoyed by a wonderfully crafted, utterly lived-in performance by Marion Cotillard, Two Days, One Night subtly but pointedly makes observations of contemporary daily struggles and modern job market woes. Yet without ever seeming preachy or drifting towards melodrama, directors/writers Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne take a very simple premise (in this case, of a woman trying to save her job) and explore the complicated facets of the human condition with utmost care, precision and most importantly, a bracing sense of humanity.