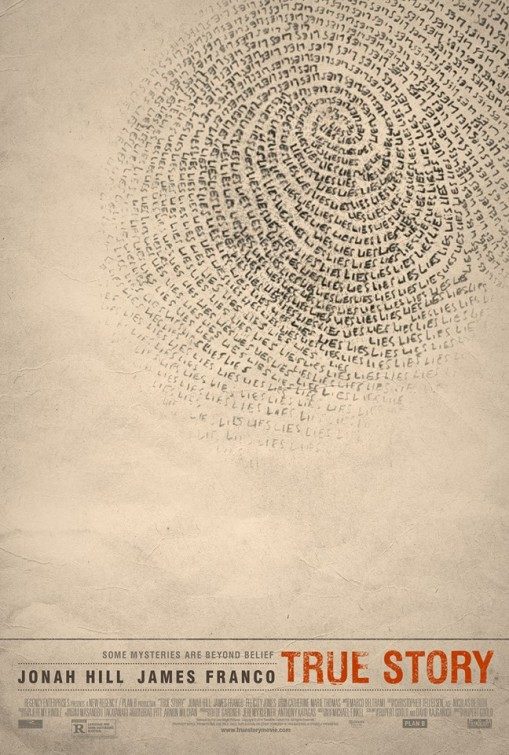

In film, the words “true story” mean very little. As we learn in Rupert Goold’s True Story, they can mean just as little off the screen. True Story is a film about men who search for and manipulate the truth, and lose themselves in the process. It’s a compelling look and journalistic integrity and a fascinating character study. Yet it’s difficult to shake the feeling that the filmmakers are wading into the same murky waters they indict the film’s central characters for inhabiting.

Jonah Hill (21 Jump Street) stars as Michael Finkel, a New York Times reporter disgraced after creating a composite character out of three African boys to use for an article. Retreating to his home in rural Montana with his girlfriend Jill (Felicity Jones, The Theory of Everything), he is soon made aware of a man in Oregon awaiting trial for murdering his wife and three children. The man’s name is Christian Longo (James Franco), but when he was apprehended, he was going by the name Mike Finkel. The real Finkel travels to Oregon to seek the truth, and instead finds a peculiar connection with Longo.

True Story draws on some fascinating subject matter: both the actual events, and the book by Finkel that they inspired. It’s a story that’s equal parts murder mystery, character study, and meditation on the nature and power of truth. Goold narrows the scope, focusing on the relationship between Finkel and Longo to create the film’s narrative core. It’s an appropriate decision, especially given Goold’s theatre background, that allows the performances to remain in the spotlight. However, one gets the feelings we’re watching events through a sort of vitriolic retrospective lens. True Story damns the manipulation of the truth, but compulsively avoids calling attention to its own distortions. On one hand, this keeps the film from slipping down a metafictive rabbit hole, but on the other, it prohibits the film from evolving into a more universal meditation on ideas of journalistic integrity in art.

Jonah Hill turns in one of the best performances of his career. Straddling the exhausting line between journalist and opportunist, he attempts to wring some amount of sympathy for a man lost inside his own ego. It’s certainly not a flattering portrayal, but Hill’s performance is nuanced and exhibits a ferocity we’ve yet to see from him. Working opposite Hill’s almost manic energy, James Franco’s Longo is steely eyed and deadly calm. It’s a deceptively complicated performance that manages to be simultaneously charming and deeply disturbing. Felicity Jones doesn’t quite fit in to the taut crime narrative, but she uses the little screen time she’s given to steal every scene she’s in, including what might be the best in the film. All around, the performances are excellent, elevating a script by Goold and David Kajganich (The Invasion) that is sometimes too on-the-nose.

Goold clearly knows how to get the best out of his actors, but True Story is still noticeably the work of an unseasoned filmmaker. Seemingly determined to get the most out of Masanobu Takayanagi’s (Silver Linings Playbook) camerawork, Goold liters the films with slow motion flashbacks that would feel more at home on a cable TV crime drama than in a character drama. The editing from Nicolas De Toth and Chistopher Tellefsen is suitably understated, while creating a subtle sense of tension that underlines the drama. True Story is a film that works best when it gets out of the way of its performances.

The Verdict: 3 out of 5

It can be difficult to create tension when the film’s final twist is just a Google search away, but Rupert Goold has crafted a compelling dance between two adept liars, each leaning on the other for opportunity and genuine empathy. Jonah Hill, James Franco, and Felicity Jones each give exceptional performances. In a strange way, True Story would be more successful if it were a purely fictional affair. But Longo’s crimes are real, and the film’s compulsion to leave its role in relation to the actual truth unexplored feels almost cowardly. There are scenes in True Story that almost certainly did not happen, but were included because it made the film a better film. When the film spends so much time condemning its protagonist for making the same artistic decision, it’s a little difficult for the irony not to work its way under your fingernails.