There’s a scene towards the end of the movie that encapsulates a lot of what The Skeleton Twins is about. Bill Hader plays a failed actor named Milo who has…misrepresented…his status in Hollywood. In an earlier scene, another character has given Milo a screenplay to read and (hopefully) pass on to Milo’s agent (who does not exist). A little later, we see Milo reading the screenplay only to express his disgust at its lack of quality. It culminates in this scene, where the character who wrote it hopefully asks, “Did you read my script?”

“Yeah, it was great,” says Milo. “I’ll definitely give it to my agent.”

The Skeleton Twins basks in this sort of irony, something not so different from gallows humor. There’s a haunting quality to the film overall, but one of the film’s biggest selling points is that it’s never limited to something so ephemeral as that. Milo and his twin sister Maggie (Kristen Wiig) have demons aplenty, and the movie does a great job of suggesting many of them. There is, for example, a photo of Milo (who is gay) arm in arm with another man that we see Milo drop into a fish tank at the beginning of the movie right before he attempts suicide (back to this in a moment). The man is never brought up again the rest of the movie, but how can we forget his existence? Likewise, no one knows that Maggie, too, is about to try to kill herself when she receives the call about Milo, but it lingers over her every action. Even brief flashbacks to Maggie and Milo’s childhood, short happy remembrances of a Halloween spent with their now-deceased father, underscore the sadness of the fact that they’ve been distant, and prior to Milo’s attempt they haven’t even spoken in ten years.

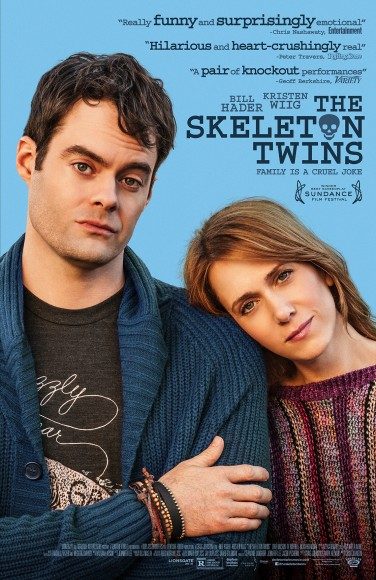

This movie seems to be marketed as a comedy almost as much as a drama, but despite a regular stream of funny moments let me assure you that it is not. Yes, both of the main characters attempt or nearly attempt suicide within the first five minutes. At its most basic, The Skeleton Twins is trying to answer the question, “Why bother?” This is a movie that plays with life’s balancing act between joy and utter despair, but by and large the happiness ledger is in the red. Which makes the decision to cast Wiig and Hader in the leading roles a gamble, but it’s paid off in spades. Milo may be depressive, but he’s got a sharp wit that Hader takes full advantage of, and one of the highlights of the entire movie is a (perhaps slightly overlong) musical sequence, part of which you can see in the trailer. Wiig is left to play everything a little more straight, but her comic timing makes Maggie feel wonderfully and tragically real, and the relationship between Maggie and Milo is consistently the most authentic part of an incredibly grounded movie.

Films looking to relationships as the antidote to suicide are nothing new, but The Skeleton Twins sets itself apart in a couple of ways. First, this is a film wholly about relational expression. We come to know very little about Maggie and Milo individually, but we understand a lot about them as they relate to other people. Second, The Skeleton Twins isn’t pulling any punches when it comes to the difficulty and complexity of human relationships. Where other films might position relationships nothing but suicide salvation, The Skeleton Twins says that relationships can also be the catalyst for extreme acts of self-destruction.

It’s hard to overstress how important a relational perspective is to the way this movie is put together. To separate the thematic, narrative, and character building elements of the movie is an impossible task because they all exists in service to the interactions among the people featured here. A lot of credit has to go to writer Mark Heyman and director Craig Johnson for building something that is so cohesive.

There is a bit of a catch-22 that emerges, though. While I wouldn’t go quite so far as to say the ending of The Skeleton Twins is unsatisfying, it does ring just a little hollow, and because I enjoyed the film so much from moment to moment, that confused me. As I dug into it, something resembling the following loop emerges.

The film is focused on relationships and relational characterization. As such, nitpicking something like, “Well, why doesn’t Maggie want to have children right now?” becomes a little bit self-defeating. What matters to the film is the effect of this decision upon her husband, Lance (Luke Wilson). At the same time, the question is legitimate. The film doesn’t hang us completely out to dry – there are some factors, both implicit and explicit, which could be contributing – but it’s a question that is important to Maggie’s perception of her own life, and it goes largely unanswered. Or alternatively, I loved the way Maggie and Milo’s current relationship is supported by flashbacks we see of them as children. Crabby and disconnected as they are after a decade estranged, it’s also believable when they act close. But then I wondered why they had been out of contact, something that’s never really explained. And that lead me to wonder why there aren’t more relational misfires between the two, especially early on. But by then I’m several mental steps removed from the actual experience of the movie, which was predominantly focused on other kinds of questions.

It’s one of those things where you have to applaud the filmmakers for making strong choices and supporting those choices, but you also wish they could have somehow squeezed in a little more meat here and there.

The Verdict: 4 out of 5

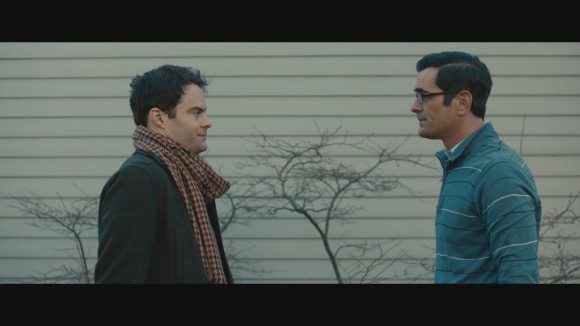

The Skeleton Twins is a very good movie, one of the best I’ve seen so far this year. Bill Hader and Kristen Wiig are surprisingly well cast in an against-type turn for both, Luke Wilson gets over some early jitters for a strong performance, and I haven’t even gotten to mentioning Ty Burrell yet, who puts in a very solid supporting effort as Milo’s on-time lover. The ending of the film doesn’t hold quite as solid as one would hope, but that should not in any circumstances undercut the reality that this is a very powerful, very real film. The balance between levity and depression is nearly perfect, as is the movie’s existence as a relational juggernaut. This is a film that begs more questions than it provides answers, and particularly given the subject matter, that’s exactly what’s needed.