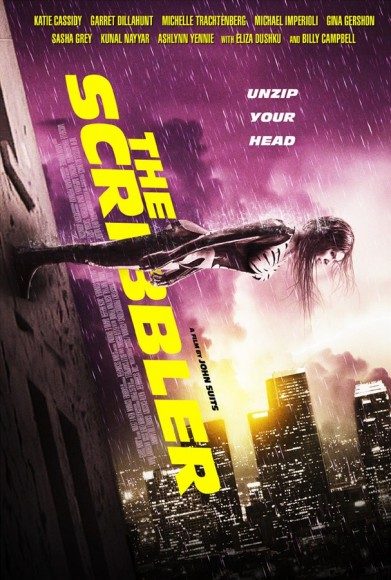

The Scribbler revolves around Suki (Katie Cassidy, Nightmare on Elm Street), a young woman with Dissociative Identity Disorder. While in the hospital, her doctor subjects to an experimental treatment called “The Siamese Burn,” which is designed to eliminate her excess personalities. After several successful rounds, Suki is allowed to finish her treatment in a halfway house for the mentally ill, lovingly dubbed the Suicide Suites, where the patients are dying at an alarming rate. As her personalities are eliminated, the body count rises, leaving Suki to wonder whether the deaths are the doing of her most powerful alternate personality: the Scribbler.

Now, that might sound like the synopsis to an intriguing, offbeat film, and maybe it is. Unfortunately, that film isn’t The Scribbler. The new film from director John Suits (Breathing Room) and writer Dan Schaffer (Doghouse) benefits from a solid hook, the kind of thing that sounds interesting when condensed down to a thirty second sound bite. Alas, the actual film is 87 minutes too long. The Scribbler is about as interested in its own plot as it is in the actual science of dissociative identity disorder: not even a little bit.

The Scribbler is the kind of film you might expect to explode out of the mind of a fourteen-year-old after he’s downed a bottle of Mountain Dew Code Red. It’s full of manic energy and eschews narrative logic and complexity with a ferocity that makes me wonder if it was intentional. Even the film’s own narrative structure works against it. The Scribbler is told as a series of flashbacks using a police interrogation as a framing device. This would be fine were the film not trying to build tension over which version of Suki survives the Siamese Burn. The film’s cards are on the table from the very beginning; any bluffing it might try to do is pointless.

Perhaps even more misguided is its attempt to portray mental illness, or at least mental instability. One does not go to a film entitled The Scribbler expecting to see a medically and psychologically accurate portrayal of mental illness. But when the entire film hinges around a specific disorder, it might want to at least read the Wikipedia article. Suki’s condition, as it appears in the film, seems more akin to schizophrenia than D.I.D. She hears voices in her head that compel her to do things, like have sex with a character because the plot requires her to. We never really experience her other identities, leaving her condition as something that’s often talked about, but rarely experienced. It’s not just Suki’s condition that is problematic. Every patient living in the Suicide Suites exhibits eccentricity, not insanity. Maybe that’s the point. But if it is, Suits isn’t interested in investigating further, and that’s damning in its own right. Mental illness is treated as nothing more than a plot device.

What The Scribbler is clearly interested in is creating a world that’s not quite our own. But whereas most films would accomplish this through careful world building, Suits and Schaffer settle for just being strange. There’s a dog who occasionally can talk; Gina Gershon (Showgirls) shows up as a snake wielding nymphomaniac; Sasha Grey (The Girlfriend Experience) makes an appearance wearing bunny ears; and there’s a woman named Alice, played by a barely recognizable Michelle Trachtenberg (Buffy the Vampire Slayer), who compulsively pushes people down the stairs. There’s definitely some entertainment value in the sheer absurdity of these elements, but they never coalesce into something that feels intelligent, or even purposeful.

The film culminates in Power Rangers style fight sequence between Suki and Alice, who becomes the film’s villain for a reason that is not satisfying, logical, or really worth talking about. They fight using super powers they’ve developed by using the Siamese Burn, which has been modified to give reveal your true self and give you superpowers. You know what, I’m just going to stop here. My brain hurts.

Verdict: 1 out of 5

The Scribbler is a film that is worse than bad, it’s disappointing. It takes a potentially interesting concept, and does its level best to squander it in every possible way. The script lacks the narrative and thematic complexity its subject requires, leaving the film feeling childish. Those that are morbidly curious should check out The Scribbler, if only to confirm all your worse suspicions about the film. But those expecting a mind-bending exploration of multiple personalities should look elsewhere, maybe the 2003 film Identity, which succeeds in almost every area this film fails.

Ultimately, the most infuriating thing about The Scribbler is how clever the film thinks it is. With all its talk of Yin and Yang, and the true nature of identity, The Scribbler is clearly aspiring to be something smart and strange. Unfortunately it succeeds only in being linear and silly on the level of a bloated student film with delusions of grandeur.