There’s a point maybe two thirds of the way into The Imitation Game where Alan Turing and the team of cryptographers assigned to decypher the German Enigma code think they’ve come upon a breakthrough. To this point, the massive code breaking machine Alan has built to crack Enigma has been whirring about nonstop without results. For all intents and purposes, it doesn’t work, an intricate mass of metal and energy that does nothing productive. Based on their new insight, Alan sets a number of switches on the machine in a particular sequence, and they set the machine loose. Within a minute, it’s arrived at a solution, and the “unbreakable” enigma code is broken.

In many ways, The Imitation Game posits that Alan is that series of switches positioned just so. Around him roars World War II, full of machines and men and moving pieces too numerous to count or keep track of. Alan is one man swept up in the movement of nations. And yet, it is his presence, his particular insertion into the massive war machine, that keys breakthrough. This is not to discredit the valiant efforts of statesman and soldiers, but to highlight how one man could still be so integral to the war effort, how one man could affect so much despite seemingly limited actions.

As much as The Imitation Game is also a biography of Turning (especially in an emotional sense), this was my strongest takeway from the movie, the one it – even to a fault – it seems most concerned with driving home. “Sometimes it is the people no one imagines anything of who do the things that no one can imagine,” is a rallying cry, a turn of phrase that is clever at first telling and never stops being inspirational, but loses the sense of being organic to the characters around the third telling. Still, the idea holds strong.

Though the majority of the film is set during WWII, sections also flash forward to Turing’s arrest for “gross indecency” (i.e. homosexuality) and back to his days as a precocious but bullied youngster in boarding school. The effect is not only to decry the terror that befell Turing and so many others at the hands of their own government, but to humanize the father of modern computing whom many contemporaries saw as an emotionless computer himself. This becomes key as the pressure on Turing builds and decisions of greater import must be made. At the outset of the movie, he’s little more than an irascible and socially unavailable genius, but over the course of the narrative we get to see Turing drawn out in a way that showcases his strength of character and deep humanity. I mean this not so much in a way that combats the still-pervasive attitude that gay people might somehow be “lesser” (although the movie is throwing that punch, too), but more in the sense that no matter how socially repugnant Turing and his enormous ego may appear at times, by the end of the film there’s no doubt about how much he agonizes over the well-being of his fellow man.

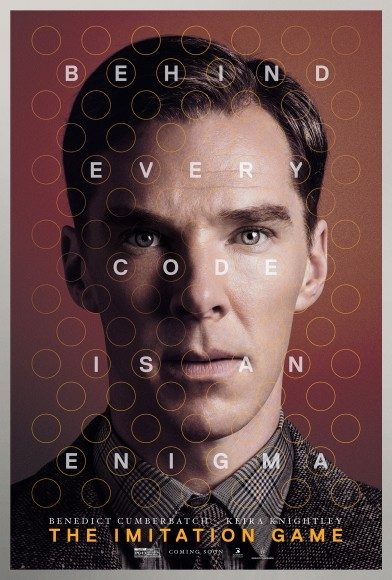

The main method for drawing Turing out are the personal connections he forms, few and far between though they are at times. Combined with the movie’s focus on emotional and psychological story and character arcs, this means that there’s a lot of pressure on the cast. Thankfully, they’re up to the task. Front and center, of course, is Benedict Cumberbatch, who’s excellent as Alan Turing. The WWII portions are the most fun to spend with him as he charges headlong into history, but it’s the slow unfolding of the postwar 1950s bits that really allow Cumberbatch to showcase his quality. Keira Knightly takes second billing as Joan Clarke, mathematics prodigy and Turing’s close friend who does much to open him up to those around him. As Joan tells Alan in a particularly amusing scene, she had to learn to be socially vibrant because, as a woman, she’s not afforded the same tolerance for irritability that Alan is. Knightly plays her with toughness belied by cultivated charisma, and she’s a pleasure to watch. Also in the mix are Matthew Goode (Watchmen) as chess champion Hugh Alexander, Mark Strong as MI6 agent Stewart Menzies, and Allen Leech (Downton Abbey) as mathematician John Cairncross, all with strong supporting performances.

Where The Imitation Game bogs down just a tad, outside of some details, is the sort of well-worn feel of the whole thing. That’s not to say that there’s anything wrong with the pieces it’s working with, at least on a large scale, but The Imitation Game feels like a movie that any number of directors could have made. The time-hopping structure of the plot is interesting, but even there, it doesn’t feel like director Morten Tyldum has really put a personal mark on this film. Has he directed a well-made movie? Absolutely. An exceptional one? That’s a bit more up for debate.

The Verdict: 4 out of 5

What’s stuck with me most since seeing The Imitation Game is almost tangential to the main thrust of the movie. I’m struck by the interplay between the film’s development of Alan Turing the tragic hero and the integral role Turing plays as a cog in the British war machine during World War II. Turning consistently comes across as a man caught up in something so much larger than himself, yet is nonetheless able to influence the movement of powerful forces he has no actual control over. Backed by a strong cast led by Benedict Cumberbatch, The Imitation Game is both accessible and compelling, an easy movie to recommend to audiences across the board.