“Quirky” is a word that gets overused. I’m guilty of it myself. So as I write this, I’m consciously trying not to use that word in association with a Wes Anderson film. If you know any of Anderson’s past work, The Grand Budapest Hotel will be immediately familiar, but that doesn’t mean this isn’t a film without a unique vision, and that starts with the framing of the story. There are three – count ‘em, three – frames to the main narrative of The Grand Budapest Hotel. A girl in a cemetery reads a book by a celebrated author. This yields to the elder author (Tom Wilkinson) narrating that story to a camera, which morphs into the voice of Jude Law as his younger self over images of the Grand Budapest Hotel as it was when he stayed there. This level of the story is occasionally recurring as a present and active part of the film, but it, too, gives way to the hotel’s elder proprietor telling the younger writer of the famous concierge M. Gustave (Ralph Fiennes), his tutor when he was just a lobby boy at the Grand Budapest in its heyday.

It’s is multi-layered framing device which lays the groundwork for the entire picture. The frames, in essence, tell the audience that it’s ok to let loose, ok to have fun, ok to enter into the story and not put too much importance on the peculiar nature of the details. I was reminded of a stage production of Peter Pan I once saw at the Lookingglass Theater in Chicago. Rather than being arranged as a traditional proscenium theater, the stage sat in the middle of the seats in a very intimate space (there were, I think, only five rows), and the production began with a character opening the book Peter Pan and inviting the audience to tell the story with the performers, many of whom played multiple roles. We in the audience were participatory only to a minor degree, but the effect was to say, “Let’s make pretend together.” It was re-living a childlike form of play, an in essence the framing device on Grand Budapest does the same thing without requiring a childlike state of mind. The story may be shown us with images on screen, but the audience is implicitly asked to imagine the story along with Anderson as the characters also tell it to us.

It’s this sort of brilliance in simplicity that makes The Grand Budapest Hotel, well, a grand old time. I don’t believe Anderson has ever been accused of being dour, and while there are moments of rather extreme violence in the film, it’s hard to characterize it as anything but fun, pure and simple. Also, because of the levity of the film, Anderson can get away with shocking an audience that has been generally desensitized to violence. It’s not something he does often but it’s incredibly effective at communicating the villainy of certain characters amidst a film that is aesthetically so bight and playful.

There’s a delightful interplay between the old-fashioned formality of high society and plain crudeness that runs throughout Grand Budapest, and most of it centers on Gustave. At times it’s casual sexual reference among an audience of nobles, in the most proper English, of course. At times it’s interrupting decorum because, well, some feeling simply can’t be expressed by anything short of a good, solid “F***!” There’s a great running joke where Zero (Tony Revolori), the lobby boy who is his protégé (and the owner of the hotel in the Jude Law/Younger Writer frame), adopts Gustave’s penchant for crafting poetry. They compose back and forth to one another, usually interrupted by running from somebody who wants to capture and/or hurt them physically.

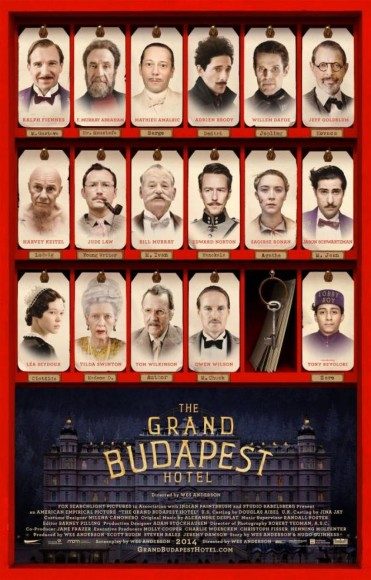

Ah, yes, the plot in that final frame. As has already been said, Gustave and Zero are employees at the Grand Budapest Hotel and are our protagonists. Among the many of Gustave’s patron-admirers is a certain Madame D., played by Tilda Swinton in a surprisingly convincing mountain of old age makeup. When Madame D. dies suddenly, Gustave and Zero go to pay their respects and learn that Gustave has been willed an incredibly valuable painting. Madame D.’s son, Dimitri (Adrian Brody), vows to fight the will, but Gustave and Zero steal the painting, going on the run from both police and Dimitri’s bodyguard Jopling (Willem Dafoe) while it comes to light that foul play may have been involved in Madame D.’s death.

The plot from there plays out a lot like a Bourne movie, actually – some characters on the run, others chasing, schemes all around – except with a little less tension and a lot more laughs. Zero’s love, a local baker’s assistant played by Saoirse Ronan, comes into the picture, as to a shocking number of other characters of varying degrees of importance. And it’s just silly. Wonderfully, wonderfully silly. On rare occasion it does go a little far, such as a “round up the posse” scene where some five other concierges are called to Gustave’s assistance, all shown in order in structurally identical bits. The first few times, it’s hilarious. The last couple, it’s too expected. But I’ll be damned if that over commitment to the film’s visual style isn’t also part of it’s appeal. Going half way wouldn’t sell the same invitation to sophisticated escapism (and again, we find the mix of the high class and the crude).

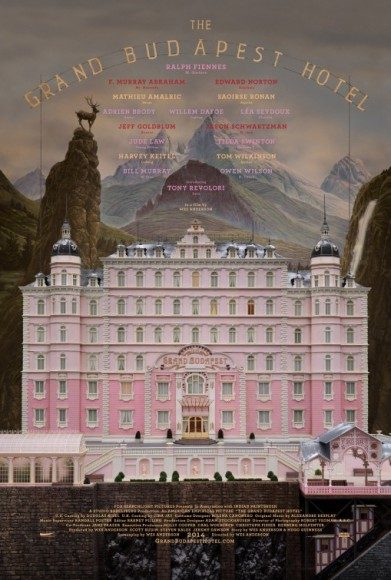

It’s worth mentioning that the production design is top notch, and very actively participates in the sense that this movie is a collaborative storytelling experience. Through each level of the frame, reality becomes abstracted by a further minor degree, so the final story takes place in a world that’s familiar, but also looks like it’s made out of paper dolls. There’s a skiing sequence, in fact, where nearly every shot is animated, but it’s not shiny photorealistic CGI, it’s stiff figurines shown in something close to silhouette that move as though a child ran them before the camera on popsicle sticks.

The Verdict: 5 out of 5

That’s what’s so special about this movie. It’s funny, sure. It’s well acted, unquestionably. But more than anything else, this movie is cohesive. Although there are a few moments that don’t feel like they work as well in isolation as might be hoped, it’s hard to argue that there’s a hair out of place in the whole production. It’s not childish fun; it’s more like you should remember what being a child was like as your now-adult self, and give yourself the license to embark on this remarkable tale with Zero the younger, Zero the older, the younger writer, the older writer, the girl reading the book, and Wes Anderson himself.