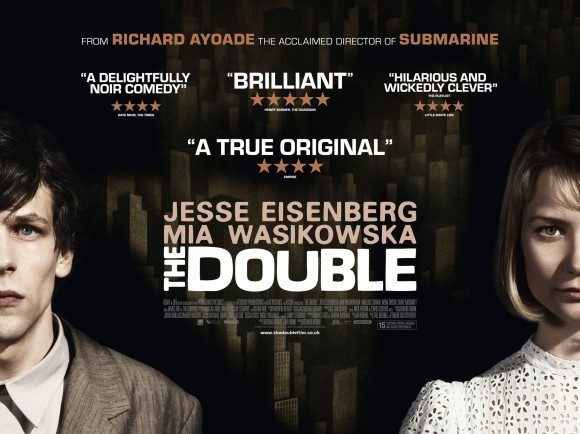

It’s impossible to discuss Submarine director Richard Ayoade’s sophomore film without mentioning its literary and filmic predecessors. While based on Fyodor Dostoevky’s novella The Double, the film might have more in common with the works of Kafka, Orwell and Gilliam. The Double wears its influences on its sleeve, but even though it’s certainly drinking from the same well, it never feels derivative. Ayoade has crafted his very own surrealist nightmare that is both funny and horrifying.

Jessie Eisenberg (The Social Network) stars as Simon James who works as a low-level technician for an idiotic boss, Wallace Shawn (The Princess Bride), at a company that compiles statistics on people. A company whose commercials boast: “There is no such thing as a special person.” And Simon is anything but special. In fact, he’s so unnoticeable that when his exact duplicate takes a job at his office, no one notices. You can’t notice a copy if you never noticed the original. Simon’s doppelganger, the aptly named James Simon (also Eisenberg), is everything James wishes he could be: confident, charismatic, and fully capable of getting what he wants.

The two strike up an unlikely friendship, Simon helping James with his work, James helping Simon woo Hannah, played by Mia Wasikowska (Stoker), the girl he’s been quietly pursuing for years. The friendship quickly turns sour as James begins taking over aspects of Simon’s life, leaving him grasping on to any acknowledgement of his own existence.

The Double exists in a world outside of time, like a 1930s nightmare of what the future might be. A colorless world of perpetual night where there are so many suicides, the police have neighbor units dedicated to them. It may not have the scale of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, but it’s meticulously realized and exact. The set design is so oppressive and well crafted, that we accept the world itself as the antagonist long before Simon’s double appears. It’s a compelling backdrop that adds nuance to the questions of identity inherent in any body double story.

All the set design in the world couldn’t save this film if Simon and James weren’t any good, but thankfully Eisenberg turns in masterful performances as both. Jessie Eisenberg has made a career of playing characters on a sliding scale from socially awkward to arrogant. The dual role of Simon and James offers him the opportunity to balance that scale by exhibiting both extremes side by side. Eisenberg has impeccable comedic timing with himself, leading to some delightfully awkward moments. A scene where James tries to tell Simon how to lick his lips sexily comes to mind. But it’s not all played for laughs, and Ayoade uses the subtlety of Eisenberg’s performance to great effect. There are moments when Simon and James could be interchangeable, and moments when they could not be more different. It’s an intriguing bit of acting, and might be Eisenberg’s best yet.

American audiences will be most familiar with Richard Ayoade from his role as Jamarcus in The Watch, while in his native England, he’s probably known best as Maurice Moss from The IT Crowd. While it may not be obvious from these on-screen roles, Ayoade is an intellectual, and The Double is interested in asking some big questions. There’s a lot at work here about the nature of identity, perception, and humanity. Thankfully the philosophy is balanced with equal measures of humor and crafted with skill.

Ayoade is an exacting filmmaker; nothing feels accidental. The camera becomes an active participant in the film, isolating Simon and pitting him against his environment. The artifice of filmmaking is always in plane sight here, and yet feels entirely appropriate. The world created by The Double isn’t a reality, it’s a headspace.

Verdict: 4 out of 5

The Double isn’t going to be for everyone. The film is far more interested in asking questions than it is in answering them and this can leave it feeling a bit opaque. But Ayoade’s sophomore feature is a compelling and intelligent bit of filmmaking. It might feel a little one-note, but The Double is thematically rich and begs to be discussed in a way not enough films do.