The Big Ask is marketing itself as a dark comedy, but to call it that is a bit misleading. Films like The Big Ask market their blend of humorous tragedy as dark comedy because no one has thought of a better term for them yet. Thomas Beatty and Rebecca Fishman’s debut feature is both dark and comedic; however, if I had to come up with just one word to describe the film, it would be “honest.”

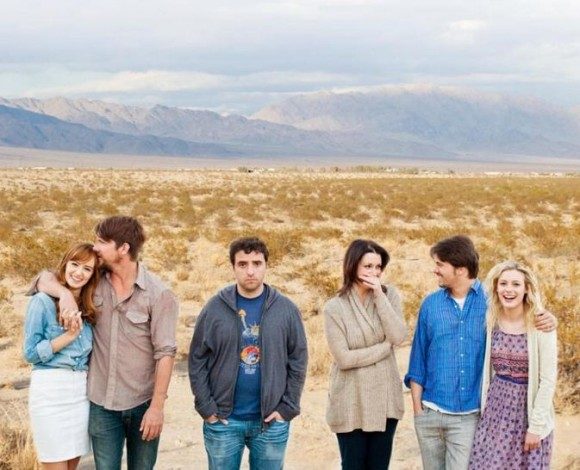

The Big Ask, originally titled Teddy Bears , follows three couples who head to a secluded desert vacation house to help their friend Andrew recover after the death of his mother. What might have been a pleasant reunion of childhood friends takes a turn when Andrew asks to have sex with all the women there, believing the foursome will help him heal. The question leaves his girlfriend Hannah embarrassed, his friends Owen and Dave angry, and their girlfriends Emily and Zoe bewildered. It’s a unique premise, and one that’s ripe with comedic potential. But where many directors would delight in playing the awkwardness for straight laughs, Beatty and Fishman spend their time focusing on how Andrew’s weaponized grief affects the group’s relationships with him and with each other.

In the absence of gags and plot-driven comedy, the film relies solely on its characters to push the action forward. Thankfully, The Big Ask is populated by a nuanced, if a bit opaque, cast of characters. The film takes the time to build realistic people with realistic problems. Zoe’s refusal to answer Dave’s marriage proposal has left their relationship in a precarious state of limbo while Owen’s relationship with Emily is threatened by his long-held torch for Hannah, whose inability to console Andrew has poisoned her confidence in their relationship. The conflicts are potent but believable and always have a way of layering into the main narrative of Andrew’s absurd request. In a film this quiet and character driven, to have so many subplots that all manage to support each other rather than distract from one another is a testament to the strength of Beatty’s script.

A script his only as good as the actors delivering the lines, and The Big Ask has collected a fantastic cast. Not only do these characters read as people, they read as people who might actually be friends with one another. There is never a sense that these people are together simply because the plot demands it. Krumholtz (Numbers) turns in a remarkable performance as Andrew, oscillating between moments of moral reprehensibility and pathos with extraordinary grace. He shoulders the roles protagonist and antagonist with an embraced sense of self-obsession and self-hatred that feels entirely human. When his friends explain the difficult position he’s put them in, he replies, “I totally understand that, and I also don’t care.” It’s a difficult headspace to embody, and one that the entire film hinges on.

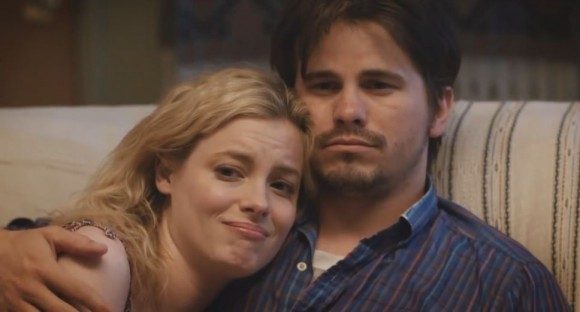

The rest of the cast puts up equally compelling and honest performances, although they are given varying amounts of material to work with. Melanie Lynskey (Perks of Being a Wallflower, Up In the Air) simmers with palpable anger and heartbreak as Andrew’s girlfriend Hannah. Jason Ritter (Freddy vs. Jason) and Zachary Knighton (Happy Endings) play Owen and Dave with a mixture of malice and compassion that feels informed by years of friendship. Gillian Jacobs (Community) and Ahna O’Reilly (The Help), as girlfriends Emily and Zoe are given the least to work with. Their connection to Andrew is a secondary one, that of a friend of a friend, and so they are rarely the source of tension. However, just because they aren’t the main players, doesn’t mean they feel any less realized.

Just because The Big Ask isn’t a light film, doesn’t mean it isn’t funny. There are certainly chuckles to be had, and even some belly laughs, but the moments of comedy all feel grounded. Nothing is played for just laughs. Even Owen and Dave’s riotous attempt to buy Andrew two prostitutes carries a great deal of emotional weight. The Big Ask isn’t about comedy, and it isn’t even about sex; it’s about using tragedy and empathy as weapons in a game of emotional warfare. An excellent film called Make Out With Violence coined this underhanded way of gaining sexual and emotional leverage with the phrase “sleaze comfort.” Sleaze comfort is a concept a lot of people with have seen or experienced in their own lives, which is one of the reasons The Big Ask feels so authentic, despite its objectively absurd plot.

Verdict: 4 out of 5

The Big Ask isn’t a great or groundbreaking film, but it’s an honest one, and sometimes that seems the more difficult film to make. It has its issues, chiefly in the third act which wraps up a bit too quickly, but the problems are slight, especially for a film from two first time directors. The film originally held the title Teddy Bears, named after the breed of cactus on which the stems of its sharp spines appear to be soft. It’s an apt metaphor for the weaponized intimacy and friendship the film focuses on. It’s a profoundly human film filled with honest performances that lend authenticity and gravitas to what could have been, in lesser hands, a cheap and forgettable film. This isn’t a film that wows in the traditional sense, but it’s a film that stays with you. The Big Ask is a small but emotionally powerful package, and one that makes its directors a pair to watch.