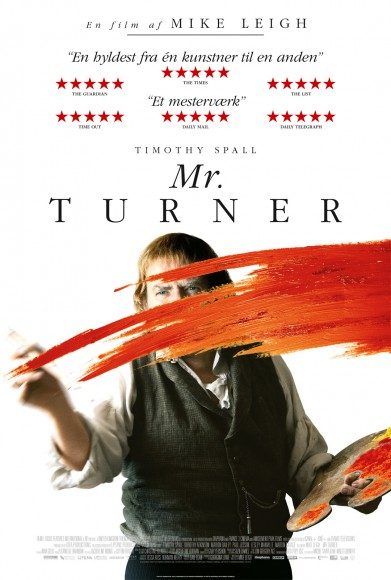

We have a notion of what an artist looks like, constructed out of romanticized biographies of Van Gogh and Picasso and shaded with pure fantasy. Writer-director Mike Leigh (Topsy-Turvy) challenges that idea in his latest film. Mr. Turner is based on the life of J. M. W. Turner, an eminent English artist who was the absolute antithesis of our romanticized artistic ideals. Mr. Turner is not so much a biopic of Turner’s career as an artist as it is a stark portrait of his complex and contradictory life as a man.

The film opens in 1820s where the 51 year-old Turner (Timothy Spall of Harry Potter fame) has already gained a fair amount of notoriety. Many of his paintings are venerated as masterpieces and he is a prominent, if somewhat contentious, member of the Royal Academy of Arts. He lives with ailing father (Paul Jesson) and doting housekeeper Hannah (Dorothy Atkinson), who suffers from psoriasis and whom Turner exploits sexually. The film follows the last quarter century of Turner’s life, but does so in a sprawling, episodic manner that eschews the strictly linear nature of tradition biography; the events depicted are notably devoid of dates. Turner rubs elbows with the elite, visits brothels, and at one point infamously ties himself to a ship’s mast to get a good look at a snowstorm. This nebulous structure suits the film’s subject, dissolving Turner’s chronology into a stirring character study.

Timothy Spall is nothing short of revelatory as Turner. He captures Turner as a contradictory union of the corporeal and the ethereal. He exemplifies this nowhere more clearly than when he paints, contrasting the works of incredible beauty with his crass method of painting which includes stabbing and spitting at the canvas. Spall creates an almost Dickensian character, communicating predominantly in grunts and growls. When he does speak, it’s in speech so plain it’s routinely profound. When a woman asks him if he paints a sunset differently than he does a sunrise, Turner replies yes, because one is going up whilst the other is going down.

Rather than construct a narrative around Turner, Leigh allows the film’s story to arise out of the character. Much of the film’s slim narrative arc concerns the three women who orbit around him: Sarah Danby (Ruth Sheen), Turner’s first mistress and mother of two illegitimate daughters Turner refuses to recognize as his own, the resilient yet marginalized Hannah, and Sophia Booth (Marion Bailey), a widow whom Turner woos under an alias. It’s to Timothy Spall’s enduring credit that Turner’s equal capacity for great compassion and great cruelty feels cohesive and organic.

Although the film remains tightly focused on Spall, Mr. Turner would not be successful without a stunning world for him to paint. Cinematographer Dick Pope (The Illusionist) creates breathtaking images that seem to exist somewhere between reality and watercolor, as he recreates the world of Turner’s paintings. The production design and art direction are also excellent, effectively transporting us to the 19th century. Mr. Turner is a film that takes time to savor both the characters and the landscape they inhabit, often providing frames that makes us pause to wonder whether what we’re seeing is reality or a painted recreation, and whether it matters one way or another.

The Verdict: 4 out of 5

Mr. Turner is a work of extraordinary care. Timothy Spall’s performance is a tour-de-force, and Mike Leigh’s film brings its subject’s life into crystalline focus with an unblinking detail that few biographies achieve. At two and a half hours, the film feels slightly stretched out in the middle, but by its end we feel as though we’ve come to know the artist as well as is possible across the centuries. To create a film the artistry of which rivals Turner’s own is an achievement indeed.