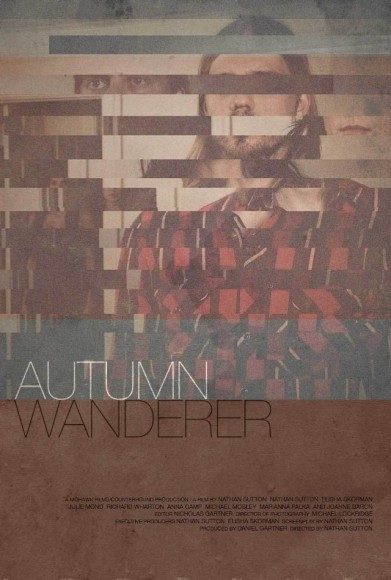

The crux of the question “Should I watch Autumn Wanderer?” comes down to this: are you looking for polished, stylistically unremarkable entertainment, or are you willing to wade through some quirks – and a few notable flaws that aren’t easily overlooked – for a movie that demands you form an opinion on the way it is made?

Autumn Wanderer is a microbudget independent feature (it was shot for just $12 thousand in only twelve days) that treads similar thematic and narrative territory to 2001’s A Beautiful Mind. The plot follows Charlie, a guy who lately can’t catch a break as he’s lost his longtime girlfriend and his drive to achievement. He’s joined by his also relationally troubled brother Rick and a mysterious new girl named Nia who Charlie meets one night while waiting for a train. Nathan Sutton wrote, directed, and starred in the pic, while the cast is rounded out by Michael Mosely (The Proposal) as Rick and Elisha Skorman as Nia. Anna Camp (Pitch Perfect, The Help) also makes a couple brief appearances as Rick’s estranged wife.

If there’s one thing that will be polarizing in Autumn Wanderer, it is the cinematography. This is where most of the film’s faults lie, but also where there is the most of interest to discuss. The film opens, and indeed is predominantly shot, in extremely long, stagnant shots. This creates a feeling that most of the picture is staged, rather than shot on camera. Frequently the camera hold steady as characters move in – and more importantly, out – of frame. Time and again in Autumn Wanderer, the audience ends up listening to a scene unfold as much as watching it, camera glued in place as the characters are halfway in another room. And it’s not something that can be written off; from the shots filling out the opening credits, we’re meant to know this is an intentional choice.

The problem is that it’s a choice that doesn’t quite work, especially early in the film. It becomes clear quickly that the story unfolding before us is Charlie’s internal struggle. There is no maguffin Charlie’s chasing, no plot device which forces him forward. I felt as I watched the movie that this was a story playing out for the first time in front of me, one in which the ending was not yet known. That’s a positive, but it means that we in the audience want to draw near to Charlie, and too often the stagnant camera left me feeling as though I was a disinterested third party that happened to catch sight of him. I wanted to see the entire story through his eyes, and it’s something that might have been solved with just a bit more active editing and/or some steady, slow camera movement. Rather than staring at the characters’ backs (as happens with some frequency), there ought to have been a cut to a close up of their faces, particularly Charlie’s. I didn’t want to be guessing at what was happening inside his head, I wanted to be shown.

There are particular points, however, where this all changes, and the camera very intentionally gives up its careful staging. With minor exception, every time Nia makes an appearance the camera switches to a close up, handheld approach. It’s about as opposite from the rest of the cinematography as you can get, and it’s a breath of fresh air. There’s an energy about Nia’s scenes that has only a little to do with the character, and it was here I actually felt like I began to know Charlie as a person. I actually began to move with him, see the world through his eyes, and there were some truly beautiful shots that resulted from this choice.

Without going too far into spoiler territory, this switching is clearly intended to communicate something about Charlie. One part of his life is stable and stagnant, the other part is turbulent but exciting. It’s a nice idea, but once again it’s a mixed bag in practice. The film seems to suggest that Charlie’s life would be better if he were to abandon himself to the Nia side of his life, but it’s not as adept at communicating why the stable part is actually a bad thing. Charlie seems like he needs stability in his life. He’s a bit of a loner, a bit of a screwup, and he’s dealing with major relational trauma that’s clearly impacting his psyche. It makes his choice, and thus his character arc, too muddled to feel like it has much significance by the time anything is decided.

A contributing factor is that it’s pretty hard to pin down exactly what Charlie’s character is. That’s not to say there’s a lack of characterization; rather, there’s too much, and too many pieces which conflict with one anther. There are a hodgepodge of isolated scenes which exist to add a little pieces to the picture of who Charlie is, but the more that’s added, the more random the resulting picture often appears. Some of it’s excused by Charlie’s personal struggles; we can accept that he might be painfully introverted in one scene and very social in another, but the way it’s played doesn’t suggest the sort of wild personality swing of someone trying to find himself. They both feel very organic (and the film is very competently acted), but that ends up being a problem.

The Verdict: 2 out of 5

All the elements of Autumn Wanderer are sufficiently competent on a technical level, which means that it’s the big, decisive artistic choices we’re left to discuss. It’s those same choices, however, particularly with regard to the way the camera is handled, that will probably turn most away from the movie. The framing for the majority of the film makes Charlie merely a player in a film where he should constantly be the subject. As a result, I never felt close enough to Charlie to fully understand him or his story, and the the film fell a little flat. There are a few too many flaws to give this film an unqualified recommendation, but it does do enough that’s interesting, and does it with such awareness, that if you like dissecting how the pieces of a movie fit together, Autumn Wanderer can be worth your time.

Autumn Wanderer is due out on VOD in February. Watch the trailer below: