Let’s take a break from new films and revisit Jean-Luc Godard’s A Married Woman, which will be coming back to theaters for a limited run.

Godard is one of those names synonymous with cinema. He has been working since the late 1950s and early 1960s and still releasing films (his last film, Goodbye to Language won the 2014 award for Best Picture from the National Society of Film Critics). Godard was one of the prominent voices of the French New Wave, right next to the likes of Francois Truffaut.

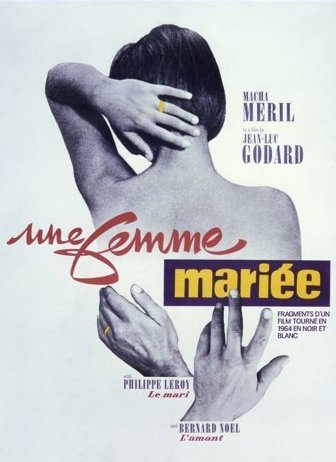

Revisiting A Married Woman should have one essential goal – see more of Godard’s films. While A Married Woman is largely problematic, it invites cinephiles and film historians-in-the-making to explore the work of such an important director. I’m guilty, myself, of not doing very much of my Godard homework. Released in 1964, A Married Woman follows Charlotte (Macha Meril), who is having an affair with Robert (Bernard Noel), an actor who is much more available than her husband, Pierre (Philippe Leroy). The film follows the interludes of Charlotte, as she remains torn staying with her husband, with whom she has a child, or leaving him for Robert.

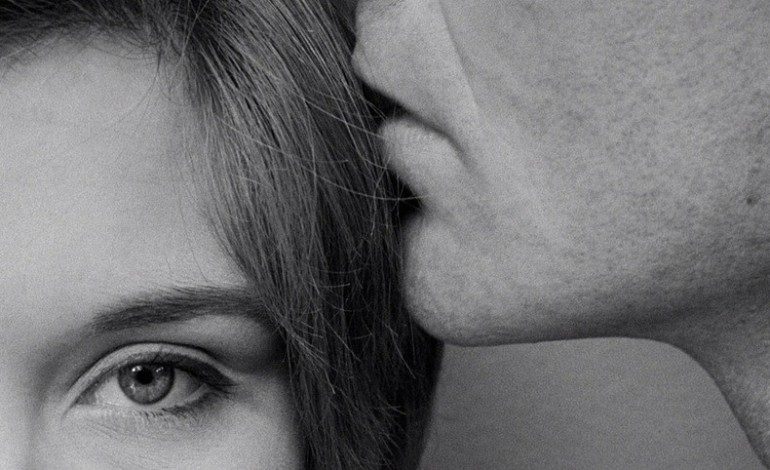

While watching the film in 2016, I tried to put myself in the mindset of an audience member in 1964. A Married Woman must have been such a provocative film, featuring extreme close-up shots of Meril’s bare stomach. What was considered risqué then is much more commonplace now.

But is A Married Woman interesting? Not really. A lot of the film is far too languid in its approach, lacking an expected amount of tension for a woman who is in the middle of a love triangle. Charlotte doesn’t seem to have much urgency in her actions, so why should we be in a hurry to care what she does? Godard doesn’t take a side in Charlotte’s affairs, which is the sign of a great filmmaker. But his abstract approach to a martial ennui doesn’t make for a riveting piece of cinema.

Verdict: 2 out of 5

There is no denying the importance of Jean-Luc Godard in cinematic history. A Married Woman moves too slowly and without much passion to be considered a film staple.